Contra d'Huy on Snake Myths

Oral histories don't last 100,000 years; our mythic root is far more recent

"The key to the interpretation of so many still hermetic motifs [...] is available to us, immediately accessible, in myths and tales still alive." Levi-Strauss

After having the idea that pronouns could falsify the claim that self-awareness was a recent discovery, I finally tracked down the paper Where Do Personal Pronouns Come From? It aims to explain why pronouns worldwide are so similar today and converge to just a few consonants 10-15,000 years ago. As the editor of Mother Tongue, a journal dedicated to studying the proposed Proto-Sapiens, the author’s theory is that pronouns worldwide have a shared root before Homo Sapiens left Africa1. The reviews are public and somewhat snarky. They pan the proposed mechanism. But all agree that the sequence of facts is sound. Pronouns really are very similar at the start of the Holocene, the edge of when linguistic reconstruction is traditionally thought possible.

This post discusses the analogous situation of dragon and snake myths in the academic literature. There is broad agreement that they are spectacularly similar. This is interpreted as evidence that myths can last 100,000 years in a condition pristine enough to keep many details. That is a long game of telephone! I argue that more recent diffusion is a better fit with the data.

d’Huy on Snake Myths

Julien d’Huy is a comparative mythologist that borrows statistical tools from genetics to construct phylogenies of far-flung myths. His research is the basis of many videos on the popular YouTube channel Crecganford:

Within academia, his findings excite colleagues enough to elicit letters such as Can Julien d’Huy’s Cosmogonies Save us From Yuval Noah Hariri? Scientific American summarizes his work: Scientists Trace Society’s Myths to Primordial Origins. From that article, I’ll let him describe his interest in snake myths (bolding my own):

My current research lends credibility to the out-of-Africa theory of human origins, asserting that anatomically modern humans originated in Africa and spread from there to the rest of the world…

I recently constructed a phylogenetic supertree to trace the evolution of serpent and dragon myths that emerged during those early waves of migrations. One proto-narrative that most likely predated the exodus from Africa includes the following core story elements: Mythological serpents guard water sources, releasing the liquid only under certain conditions. They can fly and form a rainbow. They are giants and have horns or antlers on their heads. They can produce rain and thunderstorms. Reptiles, immortal like others who shed their skin or bark and thus rejuvenate, are contrasted with mortal men and/or are considered responsible for originating death, perhaps by their bite. In this context, a person in a desperate situation gets to see how a snake or other small animal revives or cures itself or other animals. The person uses the same remedy and succeeds. I constructed this proto-myth from five separate databases by varying both the definition of serpent/dragon and the units of analysis, including individual versions of the same tale type, types of serpents and dragons, and cultural or geographical areas.

Eventually I hope to go back even further in time [sic2] and identify mythical stories that may shed light on interactions during the Paleolithic period between early H. sapiens and human species that went extinct…My more immediate goal is to expand and refine the burgeoning phylogenetic supertree of Paleolithic myths, which already includes stories of the life-giving sun as a big mammal and of women as primordial guardians of sacred knowledge sanctuaries.

First, I’d like to note that a mythologist interested in universal myths brings up both the relationship between serpents and (im)mortality, as well as women as the original guardians of sacred knowledge. I’m not cherry-picking with my theories that try to incorporate both in the story of our genesis; they are some of the most prominent global themes.

Second, he advertises that his method applied to dragon myths supports genetics in telling the Out of Africa story. He has published two peer-reviewed articles to that effect. We will start with the simpler of the two.

A simple method to reconstruct prehistoric mythology (about Saharan mythical serpents)

This is published in French, so I rely on chatGPT for the translation. d’Huy surveys snake myths in South Africa, Australia, China, North-East America, California, and Meso-America, finding support for thirteen themes almost universal to these snake myths. These are:

Aggressive mammal-headed serpent

Connected to permanent water points

Can cause floods

Takes the form of a rainbow

Connection with rain

Takes the form of a storm

Opposes the storm (inversion of the previous trait)

Manifests in the form of a violent wind

Can fly or lives in the sky

Attacks mainly women

Fights against the dragon

Can take human form

Possesses a pearl on the forehead or is linked to a crystal

There’s not much more to the paper than this. Based on the specificity of the themes, he concludes that these stories must represent a “primordial mythology, which would have spread along with the first human migrations, and that ‘the key to the interpretation of so many still hermetic motifs [...] is available to us, immediately accessible, in myths and tales still alive’ (Levi-Strauss 1948: 636).” I, of course, have offered one interpretation. His following paper does more to weave these (and other) themes together using a statistical method borrowed from biology.

The dragon motif may be Paleolithic: mythology and archaeology.

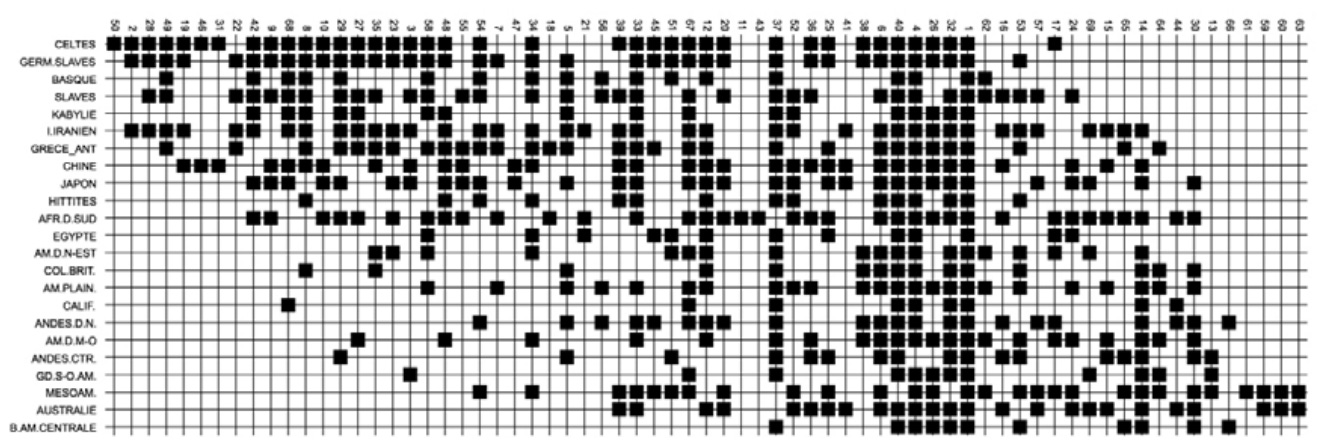

This paper3 expands the data to 23 regions worldwide and 68 different themes such as “Dragon is the creator,” “Taboo on the dragon's name,” and “Prefers women as victims.” Drawing from five different databases of mythology, he produces this matrix:

Given this series of 0’s and 1’s (whether or not a theme is present in a region), one can do all sorts of cluster analysis. Using software from biology, d’Huy builds a phylogenetic tree. This requires choosing a root4, which he sets as South Africa, reasoning: “The final tree was rooted in South Africa. This rooting is justified by the universality of the motif, which dates it back to a period before the settlement of the planet by Homo Sapiens.” The result:

To make the figure more readable, I downloaded the data and clustered it with a hierarchical method. I chose agglomerative clustering, a bottom-up method that does not require choosing a root node. In d’Huy’s figure, South Africa is the root by construction, whereas this method lets the data speak for itself (though it lacks a biological interpretation). The general structure is quite similar:

d’Huy reports several clustering methods which tend to produce four groups he describes as:

South Africa and the Far East

Australia and Mesoamerica

other Native American

Europe and the Mediterranean Basin

He contends that one can read Figure 13 (above) as a timeline, marching along the main branch to each group. Doing so, he paints this picture of our past:

“The dragon motif would then have left Africa, carried by the first human migrations, via the Near East. This first spread would have taken the dragon motif to the Far East about 80,000 to 60,000 years ago (Appenzeller, 2012), even though the oldest known trace of dragons in this region dates back only about 6,000 years, in a Neolithic tomb at Xishuipo.

From the Far East, the motif would then have spread to Australia. Two hypotheses are possible here: the first would be an almost simultaneous diffusion in America and Oceania of the dragon motif, which would be in accordance with the diffusion of Y chromosome haplogroups (Underhill and Kivisikd, 2007) and the grouping of Mesoamerica and Australia, Australia being located at a branching preceding that of Mesoamerica. The second would be a diffusion of the motif in Australia not with the first, but with a second migration, at least 8,000 years ago, before Sahul was again covered by water (Hudjashov et al., 2007); such dating would indeed match with the estimated age of the rainbow serpent motif in this region of the world (Glowczewski, 1996). The spread of the story in America would date back to the last Glacial Maximum, between 16,500 and 13,000 years BP, when the Bering Strait could still be crossed on foot. It may have been carried out in two waves of migration, the first reaching Central America, the second covering the entire continent.

The motif would also have spread from the Far East to India, then to the Near East and finally North Africa; this migration could have begun about 50,000 years ago (Reich et al., 2009) but would have ended later. It is remarkable that at the base of the Mediterranean-European group are Egypt, the Hittites, Kabylie and the Basque Country. The populations of these regions share the mitochondrial haplogroup H, very widespread in North Africa, the Near East and Europe; it would have appeared about 25,000 years ago in the Near East, and then spread to Europe on several migration waves, the first being Gravettian.”

Criticism

d’Huy says his research lends credibility to the out-of-Africa theory. To me, the data is wrestled to fit it, stretched so thin there are all sorts of holes. First, except for the Gravettian culture, dragon myths are not evidenced until the Holocene. Aligning his data to the Out of Africa model, d’Huy claims the Dragon myth entered the Far East 60,000 years ago, acknowledging a 54,000-year gap before any evidence of the myth.

Second, he commits to groupings like Meso-America with Australia, Japan with South Africa, and Egypt with North America. It truly boggles the mind that statistics on the dragon myth can tease out cultural similarities between those groups that have persisted for 50,000 or 100,000 years. Even if all dragon myths share a root, these particular pairs are best explained by noise, convergent evolution, or other processes.

Third, the idea that myths are so stable collapses on itself when you apply it to the contents of the myths. Agriculture was invented 11 times independently around the world starting 12,000 years ago. What caused this worldwide transition is a mystery to science and the subject of many myths. If some myths last 100,000 years, then myths describing earth-shattering social developments 10,000 years ago should contain many details.

Let’s see where that leads us. Agriculture in the Fertile Crescent began 12,000 years ago, and Genesis was written down 3,400 years ago. This is just an 8,600-year gap. As the story goes, after being tempted by a serpent with knowledge of good and evil, Adam and Eve became self-aware and were cast out of the Garden. One of the results was tilling the land. Henceforth by the sweat of their brow they did eat. One hears echoes of the same tale in Hesiod’s Golden Age, which descended into the Silver coinciding with the introduction of agriculture. Drawing from archeology in the region, Gobekli Tepe is the first temple, built right at the time and place agriculture was invented. It is absolutely crawling with snakes. That’s quite a detail to get right; I think these stories may be an early Neolithic preserve. Consider your reaction to my claim that the Bible references rituals held at Gobekli Tepe 8,600 years earlier. Now add another 92,400 years of oral tradition and think how much of a myth would be left. For d’Huy, enough to statistically determine a relationship between South Africa and Japan.

When claiming that myths can last 100,000 years, d’Huy cites the seminal work of Harvard philologist Michael Witzel: The Origins of the World's Mythologies. Like d’Huy he notes that snakes worldwide are connected to flood myths. Instead of interpreting this as evidence that they originated or diffused during the end of the Ice Age when sea levels rose 100 meters, he assumes they must all share an African root. This forces the myth to last 10x as long and be the result of a flood that was surely 1/10th as significant. It’s not exactly the most parsimonious explanation.

I could go on. For the Aztecs, corn is a gift from Quetzalcoatl, the feathered serpent. But rather than beat this drum, it is more productive to suggest an alternative explanation for the marked similarity of snake and dragon myths worldwide.

I propose the serpent myth emerged when and where it was first evidenced and then diffused worldwide. The earliest depiction of a snake I’m aware of is from the research of Genevieve von Petzinger, who reports that the serpentiform (idealized serpent squiggle) started appearing in rock art 30,000 years ago in Europe. Similarly, the Mal’ta-Buret culture of Siberia contains burials with carved serpents and Venus Statues (connecting it to the European Gravettian culture) 24,000 years ago. Genetically, the Mal’ta-Buret culture is called the Ancestral North Eurasians, ancestors of the Native Americans. Within Eurasia, their descendants have spread from East Asia to Europe. From there, the story could have diffused to much of the world around the end of the Ice Age. This would explain why snakes are connected to floods, agriculture, and civilization, the major shifts 10,000 years ago when the story was spreading. In the Scientific American article, d’Huy says an indigenous African myth diffused into Southern Africa 2,000 years ago5. He is open to other myths diffusing, but not dragons. No need to make them a special case!

As for the clustering method, I don’t take it all that seriously. The cultures alive today are built on many layers of migration, borrowing, conquest, and narrative innovation. It’s unrealistic to construct a 100,000-year phylogenetic tree when we can only observe leaves growing from this mess of branches. The history of our myths is more of a briar patch than a tree. To whit, consider the UMAP projection of the dragon myth below. The clusters are from another run of agglomerative clustering. This is the same data d’Huy used; the difference is I don’t enforce South Africa as the root. As much as the out-of-Africa theory, these clusters support the theory that the Americas were a Phoenician colony. Or maybe the dragon myths of the Native Americans were originally told in reformed Egyptian. How seriously do we take the method when it suggests relationships unsupported by genetic studies? That is its true epistemic value.

Conclusion

Like the first person singular, serpent myths are shockingly similar worldwide. As in linguistics, this causes some mythologists to assume that this is due to a shared root 100,000 years ago before humans left Africa. I don’t think that follows. Diffusion starting 30,000 years ago and speeding up in the Holocene can completely explain both phenomena without positing a pristine game of telephone stretching to before many linguists think we had recursive language. If myths could last that long, there would be far fewer mysteries in prehistory, including what it was like to “come online” with recursive thought.

The mechanism is a bit more complex than pronouns being invented in Africa, and being preserved for 100,000 years. He thinks they may not have had pronouns, but had words like "mama" and "papa" which are indeed similar the world over. These could have independently morphed into pronouns the world over (or done so in Africa).

Tidier support of the idea that scholars interpret similarity in languages now as evidence for genetic relations 100,000 years ago can be had in the same author’s paper The Proto-Sapiens Prohibitive/Negative Particle *Ma, which provides dozens of examples of the prohibitive (i.e. not) being potentially cognate.

“Transitively, this near universal presence in high-level linguistic phyla strongly supports an inheritance from a common origin, namely, in the language of the ancestral population of all modern humans, namely those who, some 100,000 years ago, left their African cradle and conquered the whole world.”

I used the Pronoun example for readability, as I have already introduced the paper.

Unclear what he means by going back further in time, as interbreeding with Neanderthals happened after the Out of Africa event. Or at least that is the interbreeding most amenable to study as it is the most recent and significant.

Actual title once again French: Le motif du dragon serait paléolithique: mythologie et archéologie.

The literal translation is "The dragon motif would be Paleolithic: mythology and archaeology." but this is rather clunky in English and, according to chatGPT, does not get across the uncertainty; many alternate suggestions included variations of "possible Paleolithic origins."

ctrl-f "root" in the documentation for the software he used: https://www.mesquiteproject.org/Trees.html

“My research suggests the evolution of the Pygmalion myth followed a human migration from northeastern to southern Africa that previous genetic studies indicate took place around 2,000 years ago.”