Drinking with the Gods: The Chemistry of Bes Rituals

Blood, Milk, Venom, and one Jovial Dwarf

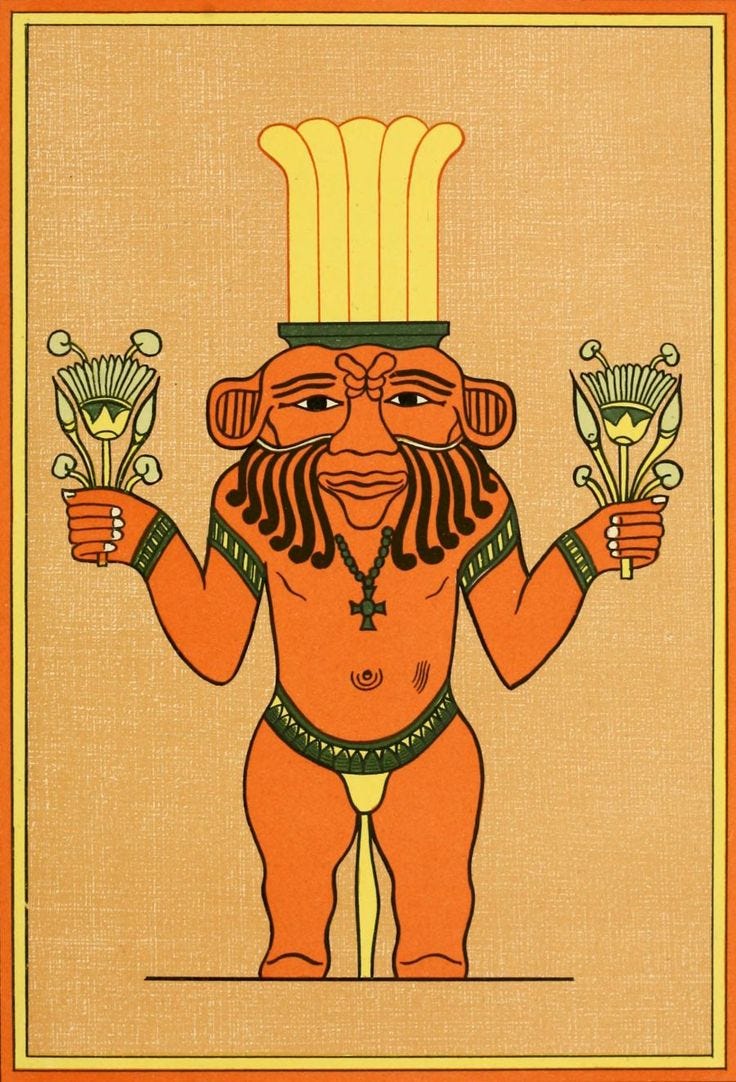

Depicted above are several libation cups made in the image of the Ancient Egyptian god Bes. The burgeoning field of archeo-botany allows us to investigate what was consumed from such ritual jugs by analyzing millennia-old residue. It was expected to be some derivative of beer and herbs, as these are standard ritual libations. However, a recent paper found this mug also included psychoactive compounds, human blood, and breast milk. The Egyptians were getting high on blood potions! The authors suggest this could have been for a ritual enacting a well-known myth involving Bes. At one point, the goddess Hathor is hellbent on destroying the human race. Bes placates her with a spiked beer. When she wakes up, the anger has passed, and humans live to annoy the gods another day.

The authors acknowledge their interpretation is speculative, but that opens the door for more subtile speculations. Even more than Hathor’s trickster, Bes is known as a protector against snakes, often depicted protecting households and children from venomous threats. Intriguingly, nearly every ingredient found in the ritual mug has known antivenom properties. If we’re going to speculate, why not make Bes a branch of the worldwide snake cult? The evidence supports it just as well.

Wanna get high?

First, let’s start with what we know. Bes was a unique figure in the Egyptian pantheon—more protector than traditional god, and one whose image was welcomed into homes, not just temples. His name likely derives from the Egyptian word "besa," meaning "to protect," but other intriguing possibilities exist. It may come from the hieroglyph "bs," meaning "flame," or "bz," meaning "to be initiated" or "to introduce"—fitting for a figure who stood at the threshold, guarding households and introducing initiates into sacred rites.

Bes' worship was remarkably widespread, enduring for millennia and extending far beyond Egypt's borders. He appears as early as the Pyramid Texts—the oldest known Egyptian religious writings—where his protective role is invoked to ward off malevolent forces. Later, his image traveled across the Mediterranean, with the Phoenicians possibly dedicating the island of Ibiza to him. They called it ʾYBŠM ("Dedicated to Bes"), suggesting his influence reached far beyond the Nile, guarding sailors and settlers alike.

Unlike many gods reserved for royal or temple contexts, Bes belonged to everyone. He protected families, pregnant women, and children from evil spirits and snakes, while his comical and fierce visage brought both joy and safety into Egyptian households.

The concoction contained wheat, fruit, and herbs—standard ingredients for ritual libations, often forming a base of spiced beer or wine. But this brew stands out for its pharmacological twist: Syrian rue, known for its psychoactive alkaloids that induce dream-like visions; blue water lily, a mild sedative and euphoriant; and spider plant, a traditional medicine with hallucinogenic properties for cats. Most strikingly, the concoction also included human bodily fluids: blood, breast milk, and mucus (vaginal?)—elements loaded with symbolic and ritual significance.

Below, I list these along with their possible utility as antivenoms:

Wheat + yeast = beer (?)

Beer mixed with herbs was the basis of snake antivenoms in both Ancient Egypt and Assyria. Together, those links show dozens of recipes from primary sources.

As for the chemistry, beer typically has negligible amounts of rutin. However, there are techniques as simple as varying the temperature of initial steps that can 60x the amount of rutin (See: Brewing Rutin-Enriched Lager Beer)

Fruit (grape or pomegranate)

The Brooklyn Papyrus also lists wine as a common ingredient to treat snake bites.

Honey or royal jelly

Egyptians included honey as a common ingredient in antivenoms.

Royal jelly contains rutin: Current Status of the Bioactive Properties of Royal Jelly: A Comprehensive Review with a Focus on Its Anticancer, Anti-Inflammatory, and Antioxidant Effects.

As does honey: Antioxidant Activity of Three Honey Samples in relation with Their Biochemical Components.

Sesame seeds

Traditional cure in India: “In the event of a snakebite: Jaggery and sesame seeds should be crushed in cow’s milk and consumed orally”

Pine nuts or oil

Couldn’t find anything venom-related.

Licorice

Counteracting effect of glycyrrhizin [licorice] on the hemostatic abnormalities induced by Bothrops jararaca snake venom: “Co-administration of [licorice extract] with antibothropic serum abolished venom-induced bleeding.”

This review adds several other studies showing an effect: Herbs and herbal constituents active against snake bite.

Additionally, they found pharmacological compounds:

Syrian Rue:

This is a traditional treatment for snakebite; however, interestingly, it was found to be detrimental to actual survival. Mice with venom + Syrian Rue died much faster than those with just venom: Effects of the Hydroalcoholic Extract of Peganum harmala Against the Venom of the Iranian Snake Naja naja oxiana in Mice. Maybe it was lacking some sort of preparation?

Interestingly, it is a good source of rutin: In vitro ovicidal activity of Peganum harmala seeds extract on the eggs of Fasciola hepatica.

Blue water lily (nymphaea caerulea), AKA Egyptian Lotus

Appears in the Brooklyn Papyrus in connection with snake bites: The Brooklyn Papyrus Snakebite and Medicinal Treatments' Magico-Religious Context

Spider plant (cleome, sp. n.d)

Cleome Gynandra is used in the Ayurvedic tradition to treat snake bites.

As the species is not determined, plants from the genus Cleome are used in traditional treatments of snake bites in Uganda, Benin, Saudi Arabia, Sri Lanka, India, and Pakistan.

Finally, the human fluids:

Human blood

Modern snake antivenoms are produced by injecting horses with snake venom, causing them to develop antibodies. These are then extracted from the horse’s blood.

Breast milk

The Smithsonian writes about a herpetologist in the Congo who was spit on by a snake. In a pinch, he turned to traditional medicine and found a nursing mother to wash his eyes out with milk. This is reported as efficacious.

Sadhguru, a popular guru in India, mixed snake venom with milk when he drank it to dedicate a temple. The link is to a video of the event.

Classicist David Hillman argues that venom mixed with milk was consumed at Eleusis: “It appears that the priestesses of Hecate, Priapus, and Demeter/ Persephone were involved in the consumption of viper venom. [Aeschylus was nearly executed for revealing the secrets of the Eleusinian mysteries in his plays on Orestes. One of these plays (The Cup-bearers) contains a dream of a “dragoness” in which her breast milk is injected with the venom of a snake.]...Some of them are even called “dragonesses,” and are involved with the “burning off” of human mortality.” Direct quote, “[]” inclusive, from the book chapter Drugs, Suppositories, and Cult Worship in Antiquity.

Breast milk and serpents are also recurring themes in the adventures of both Herakles and Krishna.

Mucus

Hillman also writes about the use of vaginal excretions in these cocktails.

Bes, snake wrangler

Based on these psychoactive ingredients, the paper concludes, “it would be possible to infer that this Bes-vase was used for some sort of ritual of reenactment of what happened in a significant event in Egyptian myth.” Because the spiked brew Bes gave Hathor included blood, they suggest that episode.

Yet, no mythic event looms larger in Egyptian cosmology than the defeat of Apophis, the cosmic serpent. In Egyptian cosmology, the first act of creation occurred when Atum emerged from the primordial waters and spoke his own name, bringing the first "I am" into existence. Almost immediately, he confronted Apophis, the great serpent of chaos who existed in those waters. This established the pattern that would repeat each night when Re (who is often identified with Atum) makes his journey through the underworld in his solar barque. At the deepest hour, he confronts Apophis, who attempts to devour Re and prevent the sun from rising. This cosmic battle between order and chaos must be won anew each night. Apophis employs many tactics - trying to hypnotize the sun god's crew, flood the river of the underworld, or wrap his massive coils around the boat to halt its progress. But through magic and combat, Re defeats the serpent each time, ensuring the sun will rise again. This daily victory was so important that Egyptian temples performed regular rituals to weaken Apophis, including reciting spells and destroying wax effigies of the serpent.

Given Bes's frequent depiction as a serpent-fighter, could this ritual brew have been part of an Apophis reenactment? The problem with this interpretation is that Re and Atum fight Apophis, not Bes. However, Egyptian gods often represent different aspects of the same Divinity, somewhat like the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Dasen writes, “Bes seems to have been regarded principally as a hypostasis of the sun-god,” where hypostasis is the underlying, fundamental state or substance that supports all of reality. Further, the snake that Bes is holding in his left hand is sometimes even identified as Apophis1. As such, it doesn’t seem a stretch for the Egyptian cosmic drama par excellence to be featured in Bes’s cult.

Flower power

A final note on the inclusion of the lotus in both the concoction and depictions of Bes. My interest in these symbols began while researching the evolution of inner voice—specifically, what it would have been like when humans first started to identify with their own thoughts. This led me to creation myths, where I noticed a striking pattern: snakes and their antivenoms appeared together with remarkable consistency. Consider this depiction from India:

This pairing of serpents and lotus isn't unique to India. At Hathor's temple in Dendera, Egypt:

A snake rises from a lotus in this relief, depicting part of the creation epic, with the snake representing the primordial god. Notice how the figures are painted in doubles, emphasizing their dual nature. Some scholars even argue that the Egyptian Lotus served as their Tree of Life and influenced the later biblical tale of the snake in the Garden of Eden.

But what initially interested me was the chemistry. Snake venom is a powerful hallucinogen with dissociative effects, but any ritual use would require protection. The Lotus plant contains rutin, an effective antivenom—as do apples, which similarly appear alongside serpents in tales of divine knowledge from Eden to the Garden of the Hesperides. Finding these same elements in Bes's ritual vessel—a protective deity renowned for subduing serpents—adds another piece to my broader theory about snake cults and the origins of consciousness.

Conclusion

This is admittedly speculative territory. The archeobotanists found an intriguing combination of psychoactive substances and bodily fluids in a ritual vessel and reasonably connected it to the myth of Hathor's pacification, which explicitly involves spiked beer and blood. I suggest the defeat of Apophis as another interpretive framework, especially given Bes's role in serpent combat and the presence of multiple traditional antivenoms in the mixture. However, snake venom rituals might be a bridge too far for classicists. I emailed the authors an earlier version of this essay but received no response. As you may imagine, it's hard to cold call about the snake cult, which sounds more like a movie pitch than an academic paper.

Yet the field is gradually opening to investigating psychoactive substances in ancient ritual contexts. The contents of this Bes vessel add to growing evidence that Egyptian ceremonies, like other mystery cults of the ancient world, may have employed sophisticated pharmacological preparations. Whether these preparations included snake venom remains an open question, but one that might become more approachable as scholarship continues to explore the intersection of ancient ritual and psychoactive substances. Remember, Carl Ruck, who was about four decades ahead of his time on entheogenic use, recently wrote:

“Serpents were milked to access their venom as psychoactive toxins, both to serve as arrow poisons, but also as unguents in sub-lethal dosages to access sacred states of ecstasy.”

From India to Egypt to Greece, the same patterns emerge: serpents paired with lotus, venom mixed with milk, and rituals of death and rebirth. The contents of this Bes vessel add another piece to this ancient puzzle—one that might help us understand the first human forays into metacognition.

See Figure 8 of Wandering Bes: Emissary of Ancient Pygmy Philosophy and Lore Within Dynastic Egyptian and Bronze/Iron Age Cultures by Judith Mann.

Question: You talk of snakes and venom very generically but I would suppose that it is certain venoms that are psychoactive and that rutin and other anti-venoms are effective against certain venoms and not others. Have you considered how the geographical distributions of such snakes and such anti-venoms might play into your theories?

On emailing academics about this sort of thing (speaking as someone who has been on the receiving end of many an email purporting to contain the Truth about how the Universe works that Big Physics doesn't want us to know): I'd recommend avoiding sending full article drafts and instead either ask a small number of bullet-point questions or try to talk them into a chat ostensibly about their work where you may be able to naturally include this. There is so much garbage out there, a draft post can very easily be drowned out by noise.