The Hitchhiker's Guide to Creation Myths

Testing OpenAI's Deep Research on Myths of the Origin of the Human Condition

The role of women and serpents in creation myths is the perfect test case for OpenAI’s deep research. Readers are likely familiar with the ground, so they can spot-check claims. Further, no such specific research question has ever been asked in a book format1. The prompt is provided below. In the document, I leave the citations (which failed to copy-paste) as 【?†L??-L??】and include pictures of my choosing (often with some context relating it to my research in the caption). I was extremely impressed with the analysis. It didn’t bite too hard on women and snakes, providing some myths where neither were present.

Prompt: Provide a well-researched comparative summary of creation myths from diverse cultures worldwide. Focus specifically on myths that explain the emergence of human consciousness, civilization, or the human condition—rather than purely cosmological origins (e.g., where the earth came from). The selection should be representative across regions, including but not limited to Indigenous American, African, Near Eastern, Indian, East Asian, Oceanic, and European traditions. Include at least 20 cultures.

Emphasize the roles of women in these myths, especially as bringers of knowledge, catalysts of transformation, or figures associated with the origins of self-awareness. Additionally, pay special attention to serpents and dragons, particularly in their symbolic connections to wisdom, danger, chaos, or initiation into a new state of being. Where possible, draw connections between these motifs across cultures.

Creation Myths of Human Consciousness and Civilization: A Global Tapestry

Creation myths from cultures around the world often delve not only into how the world began but also into how humans attained consciousness, knowledge, societal order, and the burdens of the human condition. In these rich narratives, women frequently appear as pivotal figures—mothers, tricksters, teachers—who bring wisdom or change, while serpents or dragon-like creatures often symbolize wisdom, chaos, or the dangerous pursuit of knowledge. Below is a journey through at least twenty diverse creation stories, each presented in its cultural context. These myths explain in their own terms the emergence of human self-awareness, civilization, and existential struggles. (Comparative notes are added only after each myth is told on its own terms.) All interpretations are supported by scholarly references.

Inanna and the Sacred Me of Civilization (Sumerian, Mesopotamia)

In ancient Sumer (Mesopotamia), the goddess Inanna (also known as Ishtar) is celebrated as a bold bringer of civilization. In one myth, she sets out to obtain the Me, the sacred powers or decrees that underlie human civilization, from Enki, the god of wisdom. These Me are described as divine ordinances covering all aspects of cultured life—law, art, music, lovemaking, kingship, weaving, and more—the very blueprint of society. Inanna visits Enki’s city, Eridu, and through a shrewd and convivial encounter (often involving a drinking feast), she convinces the wise but unsuspecting Enki to gift her hundreds of these Me. After Inanna sails home to Uruk with her prizes, Enki realizes what has happened and attempts to retrieve them, but Inanna’s plan prevails. Safely in her own city, the goddess bestows the Me upon humanity, giving rise to organized human knowledge, culture, and social order.

Inanna’s story highlights a woman as the carrier of knowledge and civilization. By her initiative, humanity in Sumerian belief received the gifts that lifted them from a simple existence to a complex civilized life. Inanna is also a goddess of love and fertility, and here her transformative power and cunning benefit humankind. Notably absent in this tale is any serpent figure—wisdom itself is guarded by a god (Enki) but then freely, if cunningly, taken by a goddess.

Enkidu, Shamhat, and the Taming of the Wild (Mesopotamia, Epic of Gilgamesh)

Another Mesopotamian story, part of the Epic of Gilgamesh (circa 2000 BCE), illustrates the emergence of human self-awareness and civilization through the wild man Enkidu. Enkidu was created by the gods from clay as a primitive, hairy being who lived among animals, knowing nothing of human ways. To civilize him, the wise king Gilgamesh sent Shamhat, a temple priestess or harimtu (often translated as a sacred prostitute). Shamhat embodies the power of female sexuality and nurturing wisdom. She finds Enkidu at a watering place and seduces him over six days and seven nights, an encounter that transforms Enkidu profoundly【?†L??-L??】. After this union, Enkidu finds that the animals no longer accept him; he has lost his wild innocence. But in exchange, “his mind had awakened” and “he had become wiser” (as commonly described in translations of the epic). Shamhat then teaches Enkidu to eat bread and drink beer – the staples of human diet – and clothes him【?†L??-L??】. She leads him to the city of Uruk to meet Gilgamesh, thus ushering Enkidu into human society【?†L??-L??】.

Once in Uruk, Enkidu becomes Gilgamesh’s friend and equal. Together they embark on adventures, but Enkidu’s transformation comes with a price: he becomes fully mortal and eventually falls ill and dies, leaving Gilgamesh to ponder the fragility of human life. In a coda to this epic, Gilgamesh obtains a prickly plant that can rejuvenate the old – a secret of renewed youth – only to have a serpent steal it while he bathes, carrying away humanity’s chance at regaining youth【?†L??-L??】. The snake sloughs its skin as it departs, a sign of its own renewal, while Gilgamesh is left to accept that immortality and eternal youth are lost to man【?†L??-L??】.

In this Mesopotamian narrative, a woman (Shamhat) is the catalyst for Enkidu’s leap from brute instinct to human consciousness and culture – an explicitly positive role for feminine influence. The serpent here appears as a thief of a life-renewing plant, echoing a recurring motif: snakes often symbolize the cyclical nature of life or the cunning that separates humans from immortality. Enkidu’s story, combined with Gilgamesh’s loss, poignantly addresses the human condition: to gain understanding and civilization often means to lose some innocence and to face mortality.

Isis and the Secret Name of Ra (Ancient Egypt)

In Egyptian mythology, the goddess Isis is a master of magic and wisdom who plays a crucial role in the civilizing of Egypt. According to a famous story, Isis sought to gain supreme power to protect her people and her family by learning the secret true name of Ra, the sun god who ruled the cosmos. Isis already knew that names held power in Egyptian belief. To achieve her aim, the clever goddess created a serpent from the dust of the earth mixed with Ra’s own spittle, and placed this magical snake in Ra’s path. The serpent’s bite poisoned Ra, causing him great agony. No other god could heal him, so Isis offered to cure Ra on one condition: that he reveal his hidden true name to her. Desperate, Ra agreed and whispered his potent name to Isis. Armed with this knowledge, Isis uttered the name in her healing spell, cleansing the poison from Ra.

By obtaining Ra’s true name, Isis gained power equal to the sun god and thus enabled her husband (and brother) Osiris to become the first divine Pharaoh of Egypt. Under Osiris’s just rule, taught and assisted by Isis, Egyptian civilization flourished. Myths say Osiris taught humans agriculture, the making of bread and wine, and laws, while Isis taught women domestic skills like grinding grain, weaving, and healing arts. The reign of Osiris and Isis was a golden age of peace and plenty. Even after Osiris was murdered by the trickster Set, Isis’s wisdom and magical skill (now bolstered by Ra’s secret) allowed her to resurrect Osiris long enough to conceive their son Horus, who would eventually avenge his father and rule.

This Egyptian tale casts a woman, Isis, as a bringer of knowledge and civilization, using her wit to unlock divine secrets for the benefit of the world. A serpent is her instrument – here symbolizing both danger and wisdom. Unlike in some myths, the snake in Isis’s story is a tool of the goddess rather than an independent trickster; nonetheless, it represents the chaotic or dangerous aspect of wisdom that must be mastered. The outcome is profoundly civilizing: through Isis and Osiris, humanity learns agriculture and social order, reinforcing that the gods (and especially goddesses) provided the blueprint for Egyptian society.

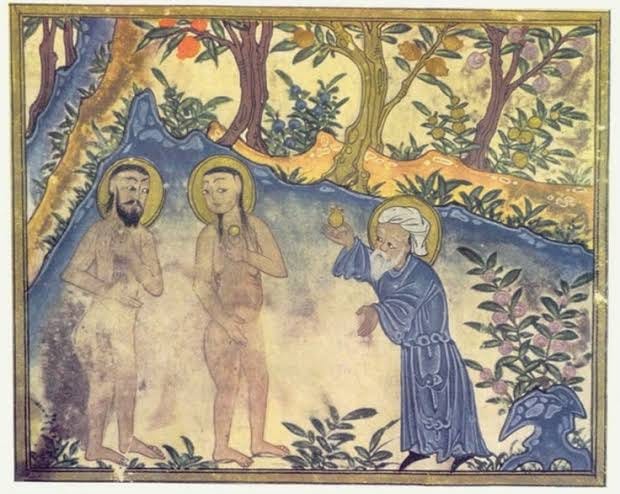

Adam and Eve and the Forbidden Fruit (Hebrew/Abrahamic Tradition)

The Hebrew Genesis account (shared with Christian and Islamic traditions) presents a creation story where the emergence of human moral consciousness is front and center. God creates the first man (Adam) and later the first woman (Eve) in the idyllic Garden of Eden. They live in innocent harmony with nature, but are given one command: not to eat from the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil. A serpent – “more crafty than any other wild animal” – approaches Eve and convinces her that eating the forbidden fruit will not lead to death as warned, but will instead open her eyes, making her and Adam “like God, knowing good and evil” (Genesis 3:5). Eve succumbs to temptation and takes a bite of the fruit, and gives some to Adam, who also eats.

Immediately, the world changes for the couple: “Suddenly their eyes were opened to a reality previously unknown. For the first time, they sensed their vulnerability”. In that moment of awakened self-awareness, Adam and Eve realize they are naked and feel shame, hastily covering themselves with fig leaves. This act symbolizes the dawn of human conscience and self-consciousness – an awakening to morality, free will, and also guilt. When God discovers their disobedience, Adam and Eve are expelled from Eden into the harsh world. They must now toil for food and suffer mortality. God notes that the humans have indeed “become like one of us, knowing good and evil”【?†L??-L??】, but as a consequence, he bars them from accessing the Tree of Life, lest they eat of it and live forever. A cherub with a fiery sword is set to guard the way back to the Garden (Genesis 3:22-24).

In this foundational myth, a woman (Eve) is the first to grasp the fruit of knowledge, effectively becoming a catalyst for human self-awareness and the complicated moral life humans now lead. The serpent is the instigator – a dual symbol of wisdom and deceit, often later interpreted as a form of trickster or even Satan. Humanity gains knowledge and a sense of good and evil, but at the cost of innocence and immortality. In theological terms, this “fall” explains why human life is marked by labor, pain, and death, but also why we possess the capacity to understand and choose – a truly double-edged gift.

The Eden story explicitly links knowledge with loss of innocence. It casts a woman in the role of knowledge-bringer (though later tradition often blames her for the fall, the narrative itself simply describes her actions resulting in greater awareness). The serpent’s role cements the reptile’s association in Western thought with cunning enlightenment and peril. This myth poignantly addresses existential questions: Why do we know right from wrong? Why do we suffer and eventually die? The answer given is that such is the price of moral knowledge – a very direct take on the emergence of human self-awareness and its consequences.

Mashya and Mashyana: The First Mortal Couple’s Temptation (Persian, Zoroastrian)

In the ancient Persian (Iranian) Zoroastrian creation story, the first man and woman are Mashya and Mashyana. They emerge after a series of primordial events: first, the wise Lord Ahura Mazda created a perfect spiritual world and a primeval man called Gayomart (or Keyumars). The evil spirit Angra Mainyu (Ahriman) attacked and killed this first being. From Gayomart’s dying seed, a rhubarb-like plant grew, and after 40 years it split to reveal Mashya and Mashyana. At birth, this human couple was innocent, and for a time they lived in harmony with creation, sustained by water and plants, and instinctively praising Ahura Mazda.

However, the evil Ahriman was not done corrupting creation. He approached the couple with lies and temptations. In some versions of the tale, Ahriman gives them goat’s milk and later meat to eat – the first time they consume animal substances – which weakens their pure nature. Over time, they forget to offer praise to Ahura Mazda and even declare that the evil spirit must be the creator of the world【?†L??-L??】. By these deceptions, Mashya and Mashyana fall from their initial state of grace. As a result, they lose the immortality or bliss that might have been their destiny. They become fully mortal and subject to suffering. For 50 years, they are unable to have children, as evil’s influence lingers. (One harrowing version even says that in their corrupted state, they cannibalized their first offspring without realizing it, illustrating the depth of human fallibility when cut off from divine guidance.) Eventually, they repent and turn back to the light, and thereafter bear the first human children, who spread to populate the earth.

In this Zoroastrian myth, man and woman are co-creators of the human race, equally sharing the consequences of their choices. Ahriman’s trickery parallels the serpent in Eden – evil manifests as a deceiver (though not in serpent form here) that twists the humans’ perception. Mashyana (the female) is not especially singled out for blame; both she and Mashya are led astray together. Their story provides an origin for the human condition of mingled good and evil. Humans are created good by a wise god, but through temptation, they become susceptible to hunger, sin, and death. Yet there is hope: by rejecting falsehood and turning back to the creator, they fulfill their purpose of populating and civilizing the world. This fits the Zoroastrian view of life as a moral struggle between truth and lies, with human free will at the center.

This Persian tale contributes the theme of a primeval fall and the loss of an original ideal state, much like Eden, but framed in Zoroastrian dualistic theology. While there is no literal serpent, the force of chaos (Ahriman) plays the corrupter. Woman and man are portrayed as partners, and the emphasis is on how false knowledge or ignorance can pervert human nature. The myth addresses why humans must work and struggle (having lost an initial ease) and underlines the role of choice in adhering to good (order) or evil (chaos).

Prometheus and Pandora: Fire and the Pandora’s Box (Greek)

The Greeks told that in the beginning, the Titan Prometheus shaped the first humans out of clay. Unlike an omnipotent creator, Prometheus was a defiant craftsman who loved his creation. In Greek mythology (as recounted by Hesiod), humans originally lived primitively, without fire or technology, until Prometheus took pity on them. He stole fire from the gods – hiding a glowing ember in a fennel stalk – and gifted this fire to humankind. With fire came light, warmth, the ability to cook food, craft metal, and forge civilization. This daring act of enlightenment made humans flourish, but it enraged Zeus, the king of the gods, who wanted to keep mortals weak and dependent.

As punishment, Zeus devised a two-fold plan. First, he chained Prometheus to a rock on Mount Caucasus, where an eagle (symbol of Zeus) would peck out his liver each day, only for it to regrow and be eaten again the next day – an eternal torment for the Titan who brought knowledge to humans. Second, Zeus sought to punish humanity for receiving the stolen gift. He ordered the creation of Pandora, the first woman, who was fashioned by Hephaestus and endowed with beauty and talents by the gods. Her name meaning “all-gifted,” Pandora was presented to Epimetheus (Prometheus’s less cautious brother) along with a sealed jar (or box) as a wedding present. Despite Prometheus’s warnings, Epimetheus accepted her. Pandora, out of curiosity, eventually opened the forbidden jar, unknowingly unleashing all forms of hardship upon mankind. From the jar poured out diseases, sorrows, vice, toil, and all the evils that afflict the human condition. By the time she managed to close the lid, the only thing left inside was Hope, which then also slipped out to comfort humanity amid its troubles.

In this myth, Prometheus is a male figure who nonetheless plays the familiar role of the knowledge-bringer or culture hero, similar to a trickster who elevates humanity. Pandora, a woman, is cast as an unwitting agent in releasing suffering. Yet her story is nuanced: the jar’s opening also ensures that hope is part of the human experience. Together, the tales of Prometheus and Pandora explain why humans possess **god-like abilities (fire, craft, intellect) but also face endless struggles, pains, and mortality. Greek writers often interpreted this as the price of progress—Zeus’s will that nothing comes to humans without cost.

The Greek creation saga underscores the double-edged nature of knowledge and civilization. Fire is explicitly a symbol of techne (craft, technology) and intellectual light. A woman (Pandora) is made the vehicle of unleashed hardship, a theme that has been critiqued by many scholars as reflecting ancient Greek ambivalence about female agency. Nonetheless, Pandora’s jar can be seen as a transition from a carefree but ignorant existence to one of awareness and hope; it is analogous to Eve’s fruit in some ways (an action that can’t be undone, changing the human condition). Notably, while Greek myth doesn’t feature a serpent in this particular tale, it does personify divine punishment and trickery through Zeus’s machinations and the symbolism of the devouring eagle.

Odin’s Sacrifice and the Gift of Wisdom (Norse, Northern Europe)

In Norse mythology, the creation of the first humans and the acquisition of wisdom are two linked but distinct episodes. The first humans, Ask and Embla (male and female), were created after the gods formed the world. According to the Prose Edda, Odin and his brothers (Vili and Vé) found two driftwood logs on the new shore and fashioned them into a man and a woman. These proto-humans had bodies but lacked the qualities of life. The three gods each bestowed a gift: Odin breathed into them the breath of life and spirit, Vili gave them understanding (mind) and will, and Vé gave them **senses and outward form (speech, sight, hearing, and a fair appearance). Thus Ask (“Ash,” the man) and Embla (“Elm,” the woman) awoke as the first true humans, endowed with soul, intelligence, and sensory perception. They became the progenitors of humankind. In this myth, we see a tripartite gift that amounts to consciousness: spirit, mind, and sense – effectively the Norse explanation for what makes humans alive and aware.

Odin himself, the chief of the Aesir gods, is central to another myth about the pursuit of knowledge. Odin is known as the All-Father and a relentless seeker of wisdom, even willing to sacrifice himself to himself to attain it. In a famous episode, Odin hung for nine nights on the cosmic World Tree (Yggdrasil), pierced by his own spear, without food or drink, in a shamanic act of sacrifice. At the end of this ordeal, he perceived the secret of the runes, magical symbols that are also a writing system【?†L??-L??】. He snatched up the runes, screaming as he grasped their power. By this sacrifice, Odin brought the knowledge of runes (writing, magic spells) to gods and eventually to humans. In another story, Odin gave up one of his eyes at Mímir’s well in exchange for a drink of its waters of wisdom, trading physical sight for inner vision and understanding【?†L??-L??】.

Women in Norse creation lore are not prominently featured as creators (Embla is passive material in the story of Ask and Embla). However, Norse cosmology and subsequent myths do give important roles to female figures in knowledge and destiny: the three Norns, for example, are female entities who carve the runes of fate for every child, including humans and even gods. Also, Odin’s quest for wisdom leads him to consult a wise prophetess in the underworld and to learn seidr (sorcery) possibly taught by the goddess Freyja. So feminine wisdom is present, if more subtly.

The Norse perspective on the rise of human consciousness is straightforward in the Ask and Embla tale: divine gifts directly grant life and awareness. Odin’s personal mythos then emphasizes that wisdom must be earned through sacrifice and suffering. There is no serpent tempting mankind here; rather, the closest is the serpent Nidhogg gnawing at the roots of Yggdrasil – a destructive force rather than an enlightener. Still, Odin’s story and the image of the tree recall motifs of seeking knowledge of fate and life’s mysteries, akin to other cultures’ quests for forbidden wisdom. In Norse myth, the price of knowledge is high, but it is pursued as a noble goal. The human condition is thus defined by having been given consciousness by the gods, and the greatest leaders (like Odin) are those who continue to seek greater understanding, even at great cost.

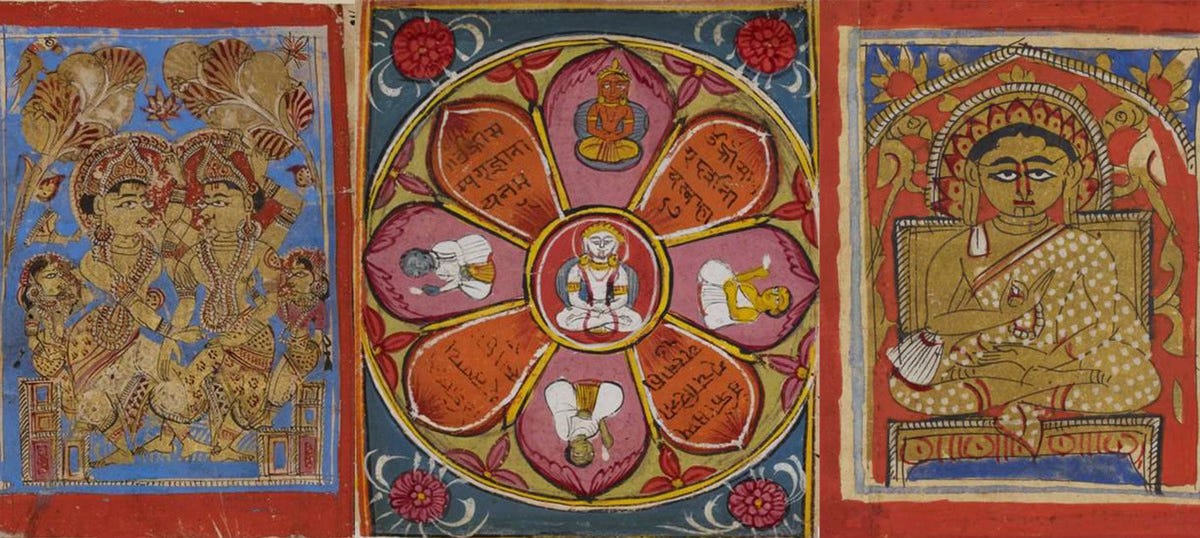

The Self Becomes Two: A Hymn from the Upanishads (Ancient India)

The Brihadaranyaka Upanishad (dating to the first millennium BCE in India) offers a philosophical creation myth focused on the emergence of duality and self-awareness. In a famous passage, the world begins as an infinite singular Self (Atman or Brahman) that alone existed. This solitary being realized, in a primordial moment, “I am,” which is described as the dawn of self-awareness. Yet, being alone, the Self felt fear and incompleteness – it was not happy by itself. To allay the loneliness, the Self split into two, becoming a male and a female locked in embrace. “He became as large as a man and a woman in close embrace; then he divided his body into two parts” says the text. From this first divine couple, union occurred and all creatures were born, “down to the ants,” as the Upanishad humorously notes. The woman, called Shatarupa or Ushas in some later retellings (and simply referred to as “his wife” in the text), initially fled from her male counterpart because, in this new existence, they stood as separate beings and she felt some shame or taboo. The male took on various forms of animals to continue creation with her as she transformed into corresponding female animals, generating all species. Eventually, they returned to human form and produced the first human offspring.

In this subtle myth, woman is literally half of the primeval Self, not a secondary afterthought. The emergence of woman and man from an original unity is the Upanishadic way of explaining the fundamental unity of all being behind the apparent duality of male and female. It also ties the origin of human life to the origin of desire and relationship – “he was not at all happy [being alone]; so he desired a mate”. This introduces the idea that relationship (between self and other) is the foundation of creation and that the yearning for completeness drives cosmic evolution.

The Upanishads do not mention a serpent or a forbidden act in this creation. There is no sense of a “fall”; rather the emphasis is on self-realization and the generation of complexity from unity. However, a later verse implies a subtle loss: once the Self became divided into two, each half began to perceive itself as a separate mortal, forgetting their original unlimited nature, which introduces avidya (ignorance) – the fundamental not-knowing of our true Self that, in Indian philosophy, is the root of the human condition. The task of life then becomes rediscovering that unity.

This Indian philosophical myth stands out for its abstract, inward focus. It frames the origin of the human condition as a metaphysical transformation – the One becoming Two – and grounds consciousness and desire at the center of creation. The female principle is coeval with the male, embodying the first manifest knowledge that “I am two.” While no serpent or trickster appears, one could say Māyā (illusion) plays a role when the halves forget their unity. The result is that humans, born into a world of duality (male/female, self/other), must navigate desire, fear, and the quest for wholeness – key themes in Hindu thought on why we seek knowledge and liberation.

The Gradual Fall from Purity: The Aggañña Sutta (Buddhist Tradition)

In a unique account from the Buddhist Pali Canon, the Aggañña Sutta, we find a non-theistic “creation” story that explains how human society and its ills came to be. Rather than attributing creation to a god or gods, this story describes a gradual evolution or devolving of pre-human beings into the humans of today, focusing on the origin of social order, labor, and moral decline. In the beginning, says the text, sentient beings existed as ethereal, luminous entities floating above the Earth. They had no gender, felt no need, and lived in a kind of blissful, everlasting light. Over time, the Earth beneath formed a rich creamy substance (like butter or foam on water). Out of curiosity and greed, one of the beings tasted this earthy substance, found it pleasant, and others followed. As they ate the Earth’s richness, their luminous subtle bodies became coarser and heavier, and they lost their ability to fly. The nutriment also caused distinctions in appearance – some grew more handsome, others less so. Pride and envy arose. As the edible earth got used up, new types of food appeared (fungi, then rice), and the beings continued to consume these. Each new food made them more material and dependent. Eventually their bodies became fully physical, and sexual distinctions emerged, male and female, leading to attraction. When these now-human beings first coupled, others, still accustomed to a previous purity, shamed them for the act. But soon such reproduction became the norm【?†L??-L??】.

As reproduction increased, people began to organize to manage their fields of rice. Initially, rice grew freely and abundantly, no labor needed. But when some individuals started hoarding rice for themselves, scarcity appeared. To deal with theft and greed, the community agreed to select a leader – the first king (called Mahāsammata, “the chosen great one”) – whose job was to maintain order and punish wrongdoers. This is presented as the origin of government and the social contract. Over time, further differentiation occurred: some devoted themselves to spiritual practice (becoming ascetics or brahmins), others to various trades. Thus the caste system and different professions arose, not from divine decree but from human choices and natural decline.

Notably, no single woman or man is responsible for this “fall”—rather it’s a collective saga of an entire proto-human race. The first instance of immorality is literally a greedy taste, reminiscent of Eve’s bite or Pandora’s curiosity, but here it’s not forbidden by any external authority – it simply has natural consequences. A serpent doesn’t appear; instead, the temptations come from within the beings themselves (hunger, curiosity, lust). The presence of women enters as part of the natural development of sex and family; women (and men) then participate in the emergence of society. This Buddhist telling is less about blame and more about diagnosing the human condition: why we have suffering, social hierarchies, and need governance. It attributes these not to divine punishment but to a gradual erosion of an original simplicity due to craving (one of Buddhism’s central concepts).

The Aggañña Sutta’s narrative serves a didactic purpose: it reinforces Buddhist teachings that desire and craving lead to suffering and the degeneration of a golden age. It’s a creation myth without a creator, emphasizing cause and effect over divine will. In terms of our themes: the story does highlight how humans acquired various kinds of knowledge (agriculture, law, social roles) but views this as a mixed blessing that became necessary only as virtue declined. A woman does not play a singular “Eve” role; instead, collective human weakness is the foe. And while no snake whispers in anyone’s ear, the concept of temptation is internalized. The end result is a fully formed human society – but with property, work, and moral failings, explaining the existential struggle that Buddhism aims to remedy by suggesting a return (through enlightenment) to that original luminosity and freedom.【?†L??-L??】

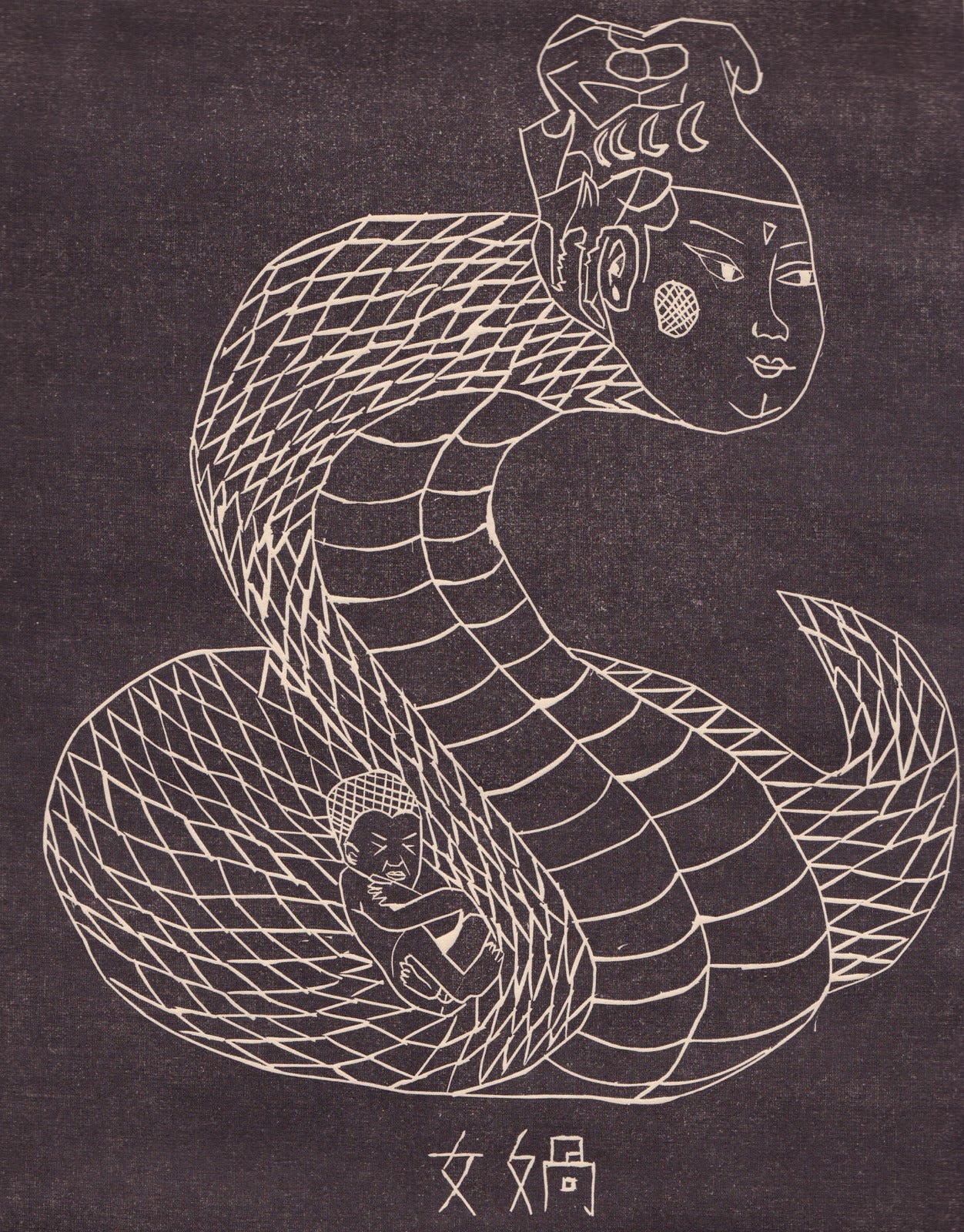

Nüwa Creates Humanity from Clay (Chinese Mythology)

In Chinese mythology, one of the most beloved creation figures is Nüwa (女娲), a mother goddess often depicted with the upper body of a woman and the lower body of a serpent or dragon. After the heavens and earth were formed (in some stories by the cosmic giant Pangu), the world still lacked creatures to fill it. Lonely in the new world, Nüwa decided to fashion beings after her own form. She began to mold yellow clay from the riverbank into figures of men and women. One by one, she sculpted them with care, and with divine power, she gave them life. These first humans, crafted by hand, were intelligent and grateful. But making each person individually was slow work. To speed up the process, Nüwa dipped a rope in the clay and flicked it, spraying droplets of mud everywhere. Each droplet that landed became a human as well. In some interpretations, the hand-crafted people became the nobility (more refined) and the spattered ones became the common folk – a later societal reading into the myth.

Once humans existed, Nüwa took on a role as their protector and teacher. In one version, seeing that the humans were ignorant of how to continue their kind or organize, she invented marriage and taught them to procreate and form family bonds. She paired men and women and introduced the norms of human relationships. Thus, not only did she create human bodies, she also shaped the beginnings of human society by instituting marriage and familial structure. Nüwa is also famous for later saving humanity: when the pillars holding up the sky were broken, she repaired the sky by mending it with five-colored stones and re-establishing cosmic order.

In Nüwa’s tale, a woman (a goddess) is the sole creator of humanity, and notably she has a serpentine aspect – combining the symbolism of the serpent/dragon (a wise, ancient being in Chinese culture) with the nurturing creativity of a mother. The serpent part of Nüwa is not evil; rather it signifies her ancient, elemental power and possibly the flexibility and continuity of life. Chinese dragons are symbols of cosmic vitality and often associated with water and fertility, which fits Nüwa’s role in shaping life. There is no fall or trickster in this story; humans do not disobey Nüwa. Instead, this myth emphasizes filial and social order as something bestowed by a maternal figure.

Chinese culture venerates Nüwa as the prototypical civilizing heroine: she creates people and then ensures they can sustain their existence through society and marriage. The myth underscores themes of order and harmony – when things fall apart (like the sky collapsing), it is Nüwa who fixes it. The presence of the serpent/dragon imagery with Nüwa highlights a key difference from Western serpent symbolism: here the dragon-tail indicates divine wisdom and creative power rather than temptation. Nüwa’s story addresses the human condition by explaining why we form families and social bonds – these are not arbitrary but taught by the Great Mother, ensuring that humanity thrives and multiplies.

Izanagi and Izanami: Creation, Death, and Balance (Japanese Shintō)

In the Shintō cosmology of Japan, the divine couple Izanagi (He-who-Invites) and Izanami (She-who-Invites) are central to the creation of the world and the kami (spirits/gods). Standing on the Floating Bridge of Heaven, they churned the primal sea with a jeweled spear, and drops falling from the spear formed the first island. Descending to this new land, the couple gave birth to the eight islands of Japan and numerous nature deities. Their union, however, took a tragic turn when Izanami died giving birth to the fire god. Grief-stricken, Izanagi traveled to the land of the dead (Yomi) to retrieve his beloved. He found her in the shadows and at first could not see her, but she told him not to look at her form. Unable to resist, Izanagi lit a torch and was horrified to see that Izanami’s corpse was decomposing, crawling with maggots and foul creatures. Izanami, now ashamed and furious at his betrayal, chased him out of Yomi. Izanagi barely escaped and blocked the entrance with a boulder, preventing Izanami (now a death goddess) from returning to the living world.

From behind the stone, Izanami screamed that she would kill 1,000 people each day in revenge for his abandonment. Izanagi replied defiantly that 1,500 people would be born each day to counter her curse. This dramatic exchange established a cosmic balance between life and death: death would forever be part of the human condition, but life would always continue to spring anew. Izanagi then performed ritual purification to cleanse himself of the defilement of Yomi. In doing so, additional gods were born from his discarded garments and washed body parts – including Amaterasu (sun goddess) from his eye and Susanoo (storm god) from his nose – further populating the pantheon.

The Izanagi-Izanami myth does not single out a woman as a knowledge-bringer, but Izanami is a creator goddess and then the first being to experience death, making her the origin of mortality. Through her story, humans receive an explanation for why we must die (because even a goddess mother died and was estranged from the living). Moreover, Izanagi’s response and the continued procreation of humans tie into why birth and death are constant. There is no serpent in this narrative, but interestingly, when Izanagi saw Izanami’s rotting form, the text speaks of thunder deities and a great serpent birthed from her decay in Yomi (in some versions, eight thunder gods were clinging to her, one at the tip of her breasts, etc., and a giant serpent was coiled around her). This imagery shows death as terrifying and chaotic, associated with serpent-like corruption, but those details are usually secondary.

Japanese creation myth intertwines the joy of creation with the inevitability of death. Female and male deities work in tandem to engender the world, and when the female is lost, cosmic order requires a compromise. Izanami’s vow and Izanagi’s retort form a mythological answer to one of humanity’s deepest sorrows: the loss of loved ones and the cycle of mortality and natality. The role of women in this myth is profound – Izanami is creatrix and the first victim of fatality, and later the fearsome Queen of the Dead. If we consider the serpent motif, it appears indirectly with death’s corruption, symbolizing the hidden danger of the cycle of life. The myth addresses existential balance rather than moral transgression: human beings are the children of the gods, fated to live, procreate, and die, as part of the natural order established by the divine pair.

Obatala and Oshun: Crafting Humanity (Yoruba, West Africa)

The Yoruba people of West Africa recount that in the beginning Olorun (the High God, associated with the sky) gave Obatala the task of creating the earth and its first inhabitants. Obatala, a wise and gentle deity, descended on a golden chain to the primeval waters, carrying a snail shell filled with sand, a white hen, and a palm nut. He poured the sand and let the hen scatter it, creating the first dry land. On this patch of earth (Ile-Ife, the sacred city), Obatala began molding figures out of clay to populate the world. However, at one point he grew tired and drank palm wine, becoming intoxicated. In his drunken state, his hand faltered, and some of the figures he shaped were less than perfect – this Yoruba myth thus attributes the origin of physical disabilities to Obatala’s lapse (a compassionate explanation that imbues those born different with a sacred connection to the god). Afterward, Olorun breathed life into the figures, and they became the first humans. Upon sobering up, Obatala vowed never to drink again and became a protector of those with deformities.

Crucially, among the pantheon of Orishas (divine spirits) that came to help shape the world, there was one female Orisha, Oshun, who played a pivotal role. Oshun is the orisha of fresh waters, beauty, and love. In some accounts, Oshun was the only female deity sent alongside 16 male orishas to establish the world. The male orishas, in their pride, at first ignored Oshun’s counsel. They attempted to create humanity and govern the world on their own, but everything they tried failed. The earth lay barren and the humans they fashioned were aimless. Realizing their mistake, the male gods finally turned to Oshun. Oshun then agreed to help, using her powerful sweet waters to revive the project of creation. It was only through Oshun’s nurturing, life-giving force that the world’s creation prospered. From that point on, Oshun ensured that love, fertility, and harmony flowed among humans. She became the spiritual mother of humanity, teaching about intimacy, healing, and community.

In Yoruba cosmology, women are central, with Oshun exemplifying how the female principle is indispensable for life and civilization. Some tales say that Oshun also **gave humanity the first divination tools (cowrie shells for Ifa divination) or taught them the importance of joy and cooperation, further underlining her role as a bringer of wisdom and culture. While there isn’t a serpent in the Obatala/Oshun creation narrative specifically, the theme of animal helpers (the hen) and the motif of mistake leading to imperfection introduces the idea that even in creation there were hiccups that explain human variety.

The Yoruba creation story highlights a cooperative act of creation with a special acknowledgment that without female wisdom (Oshun), civilization fails. It’s a powerful statement about gender complementarity in the fabric of existence. Additionally, Obatala’s zeal and slip with palm wine provides a gentle etiological tale for why misfortune or imperfection exists – not as a curse, but as part of a divine creator’s experience, to be cared for compassionately. The absence of a deceitful serpent figure is notable; instead of a trickster causing trouble, a god’s own folly and the necessity of partnership drive the plot. This emphasizes personal responsibility and the need for balance (male and female, wisdom and action) to properly shape human destiny.

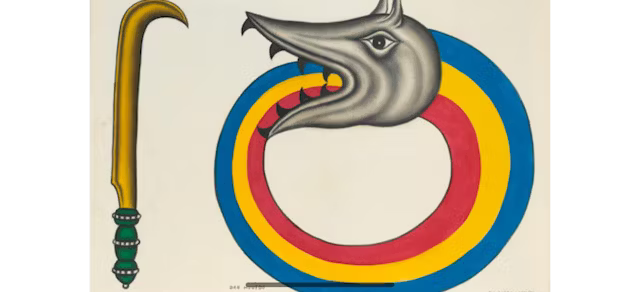

Mawu, Lisa, and the Cosmic Serpent (Fon, West Africa)

Among the Fon people of Dahomey (Benin), the supreme creator is often depicted as a dual deity: Mawu-Lisa, typically envisioned as an inseparable twin male-female pair (or sometimes as a androgynous being with dual aspects). In many accounts, Mawu is the female aspect (associated with the moon, night, coolness, fertility) and Lisa is the male aspect (the sun, day, heat, strength). Their mother is the primordial Nana Buluku, who created the universe and then delegated its ordering to Mawu and Lisa. One of the most vivid elements of the Fon creation myth is the role of the great serpent Aido-Hwedo. This rainbow serpent was created to assist Mawu. When Mawu set about organizing the earth, she rode on the back of Aido-Hwedo to travel the world and shape it. The serpent coiled and twisted, helping to carve out the valleys and mountains. Together, Mawu and the serpent filled the world with life and ensured its sustainability.

As Mawu molded the earth, she worried that it might be too heavy to support itself. At her command, Aido-Hwedo slithered underneath the earth and bit its own tail, encircling the world to prop it up. The great serpent now lies in the cosmic ocean, supporting the land on its back. To keep Aido-Hwedo comfortable (for if it shifts, the earth would quake), Mawu created the oceans for it to dwell in and fed it iron to cool its immense body. The zigzag of the rainbow in the sky is said to be Aido-Hwedo moving slightly, and earthquakes are attributed to its restless shuffling. In some versions, when creation was finished, Mawu and Lisa retired into the heavens, leaving the earth on the serpent’s back and charging their offspring or lesser gods with the details of tending life.

In this myth, Mawu is clearly a central creative force – a mother figure and organizer who is intimately paired with a serpent. The rainbow serpent Aido-Hwedo symbolizes both creative order and the fine line between stability and chaos (if the serpent moves too much, disaster could follow). There isn’t an Eve-like figure or a singular event of acquiring knowledge in the Fon story; rather wisdom is embodied by Mawu and built into the world’s design from the start. Mawu is gentle and resourceful, and Lisa brings complementary qualities, though he is less prominent in many tellings. Humans in some accounts were created by Mawu-Lisa after the earth was prepared, but the details of human emergence aren’t as elaborated as the cosmic infrastructure. Humanity is sometimes said to have sprung from Mawu and Lisa’s children or created out of clay with the help of lesser deities, but always under Mawu’s guidance.

The West African vision here emphasizes partnership of female and male, and the harmony of animal (serpent) and divine. Aido-Hwedo is a rare example of a serpent as a purely positive creative helper, showing how symbols shift in different cultures: far from tempting humans, this serpent literally holds the world together. The myth imparts a sense of balance – hot and cold, sun and moon, female and male, earth and water – as intrinsic to creation. For the human condition, the Fon myth implies that the world was carefully made with benign intent, and that we exist supported by divine care (and a snake!) beneath us. It doesn’t focus on a fall or flaw; if anything, the potential catastrophe (quakes, floods) is held at bay by the Creator’s foresight. It’s a more optimistic setup, though in Dahomey theology, humans are still expected to show reverence and maintain the balance lest things go awry.

Quetzalcoatl and Cihuacoatl: Bones, Blood, and the Birth of Humans (Aztec, Mesoamerica)

The Aztec (Mexica) people of central Mexico believed the world had passed through multiple creations (suns) and destructions. In the current Fifth Sun, the hero-god Quetzalcoatl – the Feathered Serpent – is central in creating humans. After the fourth sun perished, the gods convened at Teotihuacan to bring forth a new sun and moon and re-create mankind. Quetzalcoatl journeyed to Mictlan, the underworld, to recover the precious bones of the ancestors who had been destroyed. He managed to trick the Lord of the Dead and gather the bones, but during his escape he stumbled, and the bones broke and scattered. He carried these fragmented bones up to the world above. The goddess Cihuacōātl (whose name means "Woman Serpent") then helped him grind the bones into a fine meal in a stone bowl. The other gods shed their own blood to moisten this bone meal, and from this mixture of old bones and divine blood, the first people of our current era were formed.

Once humans were animated, Quetzalcoatl and Cihuacoatl taught them the basics of life. In some narratives Quetzalcoatl (in the form of Ehécatl, the wind god) later stole maize from the ants and gave it to humanity, with the help of another serpent deity, to ensure humans had proper food【?†L??-L??】. Cihuacoatl, sometimes called Tonantzin (Our Mother), remained a protector of women in childbirth and a guide for the Mexica. However, there’s also a darker side: Cihuacoatl was often depicted as a fearsome goddess who occasionally wails for her lost children, and she was associated with omens of conquest (the Spanish later likened her to their concept of the Weeping Woman). The Nahua concept of dualism meant that creation and destruction went hand in hand – Quetzalcoatl (light, knowledge) and his brother Tezcatlipoca (night, sorcery) often worked at cross purposes, but in the creation of humans Quetzalcoatl’s mercy predominated.

In this Aztec story, we have both a prominent male deity (Quetzalcoatl) with a serpent aspect and a female deity (Cihuacoatl) who bears the serpent title. They collaborate to bring humanity to life. The use of bones (representing the previous worlds’ dead) and blood (sacrifice from the gods) speaks to a deep notion in Mesoamerican thought: life is renewed through the death and sacrifice of others, even the gods themselves. Humans are literally made from prior beings and divine essence, which is why blood sacrifice was seen as necessary to sustain the sun and the earth – a repayment to the gods who bled for us.

The presence of serpents is strongly positive here. Quetzalcoatl’s very name identifies him with a serpent (though a feathered, flying one), symbolizing a harmonious blend of earth (serpent) and sky (bird) – matter and spirit. Cihuacoatl, “Snake Woman,” carries serpent energy in her identity as well. Neither is a tempter; rather, they are progenitors and benefactors (though Aztec myth in other contexts can cast Quetzalcoatl as a boundary-pusher or even a penitent sinner in different episodes, those are separate stories).

The Aztec creation of humans underscores sacrifice and wisdom. Quetzalcoatl must use his wits and bravery in the land of the dead, and the gods must shed blood to animate the bones. A woman-serpent deity (Cihuacoatl) is instrumental in the actual making of humans, linking femininity with the processing of raw materials (she grinds the bones) and birth. The human condition is portrayed as indebted from the very start – our life is a gift from the gods’ sacrifice, and thus the Aztecs felt obligated to return sacrifice so the sun would not cease. This myth addresses why humans are mortal (made from dead remains) yet divine in origin (given life by sacred blood), and why ritual bloodletting was woven into the fabric of their civilization’s practices.

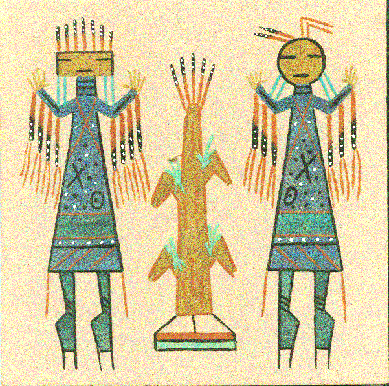

The Corn Mothers and the Vision of Mortals (Maya K’iche’, Mesoamerica)

The Maya K’iche’ epic Popol Vuh contains one of the most insightful accounts of creation focusing on the nature of human understanding. In the Popol Vuh, the divine Makers (usually referred to as Heart of Sky and Heart of Earth, or by names like Tepeu and Gucumatz which means Quetzalcoatl, the feathered serpent) attempt to create beings who can worship and speak their names. Their first attempts – animals, then mud men, then wooden manikins – fail to meet expectations: they lack speech or soul or respect. Finally, the gods procure the ingredients for the true humans. The hero twins from a previous myth secure a mountain of corn, and the divine grandmother Xmucane grinds the yellow and white maize into dough. With the corn dough, along with water, the gods fashion the first four humans. These first people are fully formed adults, and they are astonishingly wise. In fact, they are too wise – “This humanity could see far and wide, even through the stones and trees, even beyond the mountains; they understood everything”. Their sight was so clear that they could perceive the entire world and even the gods in the sky.

The Creator deities realized that these humans were almost like gods themselves in knowledge. Fearing that the humans had too much understanding and might not remember their creators with appropriate humility, the gods decided to cloud their vision. “They (the humans) could see everywhere, and the gods had to limit their sight,” one summary explains. So Heart of Sky blew mist into the humans’ eyes, blurring their vision “as when you breathe on a mirror” says the Popol Vuh. Now the people could only see what was nearby, only as mortal eyes should. Thus was human understanding deliberately curtailed – granting us knowledge and perception enough to survive, but not so much that we’d equal the gods or forget our dependence on them.

Meanwhile, the grandmother Xmucane’s role in grinding maize for human flesh highlights the importance of corn. The Maya called themselves the “People of Maize,” and indeed the Popol Vuh states corn is the very substance of human bodies. Xmucane and her partner Xpiacoc (the grandfather) are sometimes referred to as “Mother and Father” or “Grandmother of the Sun, Grandfather of Light,” and they act as elder wisdom figures aiding in creation. A pair of humble old figures, with Xmucane as a female craftsman and counselor, stand behind the miraculous formation of humanity. After the first four men are made and then four women as their mates, humanity multiplies. But soon they face challenges and migrations, which the epic continues to narrate.

In the Popol Vuh, a serpent appears early in the creation as part of the creator pair: Gucumatz is literally the “plumed serpent,” and it is he (along with Tepeu) who initially speaks the world into being and eventually participates in the creation of humans. This serpent aspect is wholly positive – a sign of sovereign plumed wisdom that stirs the waters of creation. It’s a sharp contrast to the Biblical serpent: here the serpent is on the side of the creators, not acting against them.

The Mayan myth from Popol Vuh addresses the origin of human intelligence and its limits. Humans were meant to be intelligent – made from the nourishing corn, crafted by a wise grandmother – yet the gods imposed a boundary on our perception. This introduces a distinct explanation for the human condition: we have a spark of divine insight (since we were almost gods), but our vision and lifespan are truncated to keep us mindful of higher powers. A woman, Xmucane, plays an indispensable role as the “Corn Mother” who gives humans their bodies, reinforcing the theme of feminine creative contribution. And while there is no fall from grace here, there is a deliberate dimming of human prowess, a built-in humility. Civilization (planting, grinding corn, family lineages) is seen as a gift from the ancestors/gods, and people’s job is to remember and honor that gift rather than overstep.

Manco Cápac and Mama Ocllo: Civilizing the Andes (Inca, Andes)

In the Inca tradition of the Andes (as recorded in post-conquest chronicles, notably by mestizo historian Garcilaso de la Vega), the first people were primitive and uncultured until the god Inti (the Sun) took pity on them. Inti sent down his two beloved children, a son and a daughter born of the Sun and Moon: Manco Cápac (the son) and Mama Ocllo (the daughter). This divine brother-sister pair emerged from the waters of Lake Titicaca (or, in some versions, from caves in the earth) and set out on a journey to find a place where they could civilize the people. They carried a golden staff and were told wherever it sank into the ground with ease, that would be the spot to found their city. Eventually, the staff sank at Cuzco, which became the navel of the Inca empire.

Once settled, Manco Cápac and Mama Ocllo set about teaching the wild locals how to live properly. Manco Cápac taught men the arts of agriculture – how to plant and grow maize and other crops, how to domesticate llamas, and how to build houses and irrigation canals. Mama Ocllo in turn gathered the women and taught them weaving and spinning of cotton and llama wool, how to make clothing, and the skills of cooking and managing household affairs. She was a patient teacher and was revered as a mother figure. Under their guidance, the once-savage people learned to live in villages, wear decent clothes, cultivate fields, and worship the Sun. In effect, they founded Inca civilization, with Manco Cápac often counted as the first Inca king.

Mama Ocllo is remembered as a wise and benevolent woman who was essential to bringing knowledge. In a patriarchal recording she might seem to take second place, but the Incas saw them as complementary—without Mama Ocllo’s contributions, half of society (the women) would be uneducated. In fact, all Inca nobility traced their lineages to either Manco (male line) or Mama Ocllo (female line) in various noble panacas (clans), showing her equal importance in bloodlines. The pair are also husband and wife (common in many mythologies of divine siblings), symbolizing the unity of Sun (male) and Moon (female) or Earth (female) working together.

There isn’t a serpent or dragon in this Andean myth. Instead, an important animal symbol is the condor or falcon, often associated with the sky and sometimes with Manco Cápac. Some Andean myths have a different first couple (like in Colla mythology, a male-female couple emerging from Tiwanaku), but they similarly emphasize learning and building society with the help of divine instruction.

The story of Manco Cápac and Mama Ocllo is a clear civilization narrative: humanity already existed but was living in disarray until a divine woman and man imparted knowledge and order. Here the woman’s role is explicitly to educate in domestic and artistic skills, highlighting the high value Andean culture placed on textiles (Inca weavings were extremely sophisticated) and the household economy. It’s an example of how gender roles were cast in complementary terms: the man plows and governs, the woman weaves and nurtures, and together they establish an empire. The human condition in this myth is not one of sin or fall, but of prior ignorance – a darkness dispelled by the light of the Sun’s children. In place of a serpent tempting with forbidden knowledge, we have a benevolent teacher figure handing out beneficial knowledge, which is a notable contrast to Old World motifs.

Changing Woman and the Gift of the Clans (Navajo, North America)

In the Navajo (Diné) tradition, Changing Woman (Asdzą́ą́ Nádleehé) is a central figure of creation and renewal. Unlike an “Eve” figure who causes a fall, Changing Woman is a benefactor who creates the Navajo people and their way of life. In the Navajo genesis, after a series of emergences from lower worlds, Changing Woman was born miraculously on the Earth’s surface to First Man and First Woman (or found by them as an infant). She grew to adulthood rapidly and had twin sons by the Sun (Monster Slayer and Born-for-Water, the Hero Twins who rid the world of dangers). Once the land was made safe, Changing Woman felt lonely and desired people of her own, as the existing people were the ones who had emerged from below. So from pieces of her own skin which she rubbed off from her breast, back, and under her arms, she created men and women. These became the first Navajo clans. In one version, she made four men and four women and instructed them in everything they needed to thrive. She created corn and other crops to feed them, and gave them ceremonies and songs.

Changing Woman then established the Navajo clan system, meaning she assigned each group a name and identity, ensuring that the people would remember her as their mother and stay connected through kinship. Because of this, Navajo society is matrilineal – clan identity comes from the mother. Changing Woman also introduced the Blessingway ceremonies and taught the people how to live in hózhǫ́ (harmony or balance). One of the most important ceremonies, the Kinaaldá (a puberty ceremony for girls), is directly tied to Changing Woman’s own coming-of-age and is a way the Navajo renew the world by regenerating her qualities in each generation.

Women are profoundly honored in this narrative: the very creator of the people is a woman, and she imparts not only life but culture, social structure, and spiritual practice. The idea of self-creation (creating from her own body without pain) emphasizes female autonomy and creative power. There is no tempting serpent or punitive element at all. On the contrary, the Navajo emergence myth, of which Changing Woman is a climax, frames the human condition as something that improved over time – with each world, the beings gained more order and light, culminating in Changing Woman’s gifts in this Glittering World (the surface world).

While serpents don’t play a role in the creation of people, the Navajo myths do feature supernatural snakes and monsters that the Hero Twins had to overcome (like the water monster Tééholtsódii). Those serpents represent the chaotic forces of nature that needed to be subdued for humans to live safely. But thanks to Changing Woman and her sons, those are dealt with, allowing the people to focus on living a balanced life.

Changing Woman’s myth underscores nurture, continuity, and balance. A woman is the progenitor of the people, aligning the Navajo cultural emphasis on matrilineal descent and the sacred feminine. Knowledge here is not forbidden—it is generously given. We see a theme of internal genesis (creating from within oneself) which inverts the idea of seeking something externally (like a fruit or knowledge from elsewhere). The human condition, from a Navajo perspective, is defined by being children of Changing Woman, tasked with maintaining harmony and honoring the kinship she established. The absence of a “fall” or trickster in this story, and the presence of monsters vanquished, suggests that human hardships (disease, war, etc.) are not our defining origin; rather, our origin is holy and good, and hardships are later intrusions to be dealt with through ceremony and courage. In this worldview, women and serpents stand on opposite sides – the woman as life-giver and cultural founder, the serpents as threats overcome – highlighting the victory of life and order.

Sky Woman and the Founding of Turtle Island (Iroquois/Haudenosaunee, North America)

The Iroquois (Haudenosaunee) creation myth centers on a woman from the Sky World. In that sky realm, a curious or pregnant Sky Woman (also called Atahensic in some versions) falls or is pushed through a hole under a celestial tree. Below was a vast primeval ocean with water animals. Seeing the woman plummeting, the birds (often geese or swans) flew up and gentlly caught her on their backs, saving her. The animals realized she needed land to live on, so Turtle volunteered to support land on his back. Divers – Beaver, Otter, Duck – took turns attempting to retrieve soil from the ocean floor. Finally, tiny Muskrat succeeded, surfacing with a paw-full of mud before dying from the effort. The other animals spread this mud on Turtle’s shell. Miraculously, the mud began to grow and spread until it formed an island – which expanded into North America, known as Turtle Island.

Sky Woman was placed on this emerging land. She had carried with her a handful of seeds or roots from the celestial tree. She planted these, and they became the first vegetation on earth. Before long, Sky Woman gave birth to a daughter. The daughter grew and, by some accounts, was impregnated by the spirit of the West Wind or by a dream. She bore twin boys: Good Mind (often called Hahgwehdiyu) and Bad Mind (Hahgwehdaetgah), or simply the Good Twin and Evil Twin. Tragically, the birth was fatal to the daughter – one twin was born normally, the other forced his way out of her armpit, killing her. Thus, Sky Woman’s beloved daughter died, and Sky Woman buried her. From the daughter's body grew staple plants: corn from her chest, beans from her fingers, squash from her navel – the Three Sisters crops that would sustain humanity.

Sky Woman raised her twin grandsons on the new earth. The twins embodied duality: Good Mind created beautiful features – stars, sun (from their mother’s face), rivers, animals – while Bad Mind twisted things – making dangerous mountains, thorns, snakes, and bringing conflict. Ultimately, Good Mind won a contest against his brother (in some versions, by using deer antlers to overcome him), and Bad Mind sank below the earth, ruling as the spirit of disorder (sometimes associated with winter). Good Mind (often equated with the god Tekawerahkwah, or just the good Creator) then helped Sky Woman complete the ordering of the world.

In this myth, women are at the very genesis: Sky Woman literally brings life to the earth (seeds, and her lineage), and her daughter’s body ensures food will grow. Sky Woman is revered as Earth-Mother in a sense, and Grandmother to creation. There is no insinuation of wrongdoing by these women; rather they are originators of life and mediators between the divine Sky World and the earthly realm.

A serpent appears in some Iroquoian variants not as the tempter but as part of the natural world creation or as a form taken by the evil twin (in some stories, the Evil Twin goes to live in the dark ocean and occasionally tries to overthrow the world, causing eclipses or other troubles, taking on a serpent or dragon-like form). But the serpent is not central; the primary conflict is between the twins representing our potential for both good and bad. Humans come into the story later, created by the Good Mind twin out of earth or animate clay (or simply being the descendants of Sky Woman’s lineage). All humans are considered to owe a debt to Sky Woman’s actions.

The Iroquois creation story richly symbolizes cooperation between species (animals and a woman) to create habitable land. It celebrates female creative power – Sky Woman as the catalyst for earthly life and her daughter as a sacrificial mother of agriculture. The theme of dualism – light and dark, good and bad – in the twin motif directly addresses the human condition: why our world contains both beneficence and malice, life and death. But unlike an Eve scenario, the woman is not blamed; in fact, she is honored as the first leader and first teacher. After descending, Sky Woman instructs the animals and tends the garden of the world. Some Haudenosaunee interpretations even credit her with establishing the balance of roles: women tend the earth’s growth (as she did with the plants) and hold familial authority, while men, symbolized by the animals’ strength, protect and provide. This myth also underscores gratitude: humans in Iroquois culture give thanks in the Thanksgiving Address to Sky Woman, the earth, the corn, and all elements born of this primordial story, reaffirming that conscious, moral life is only possible because of the gifts of the feminine and the natural world.

The Rainbow Serpent and the Wawalik Sisters (Australian Aboriginal Myth)

Across Aboriginal Australia, the Rainbow Serpent is a powerful creator being, often embodying the generative forces of water, rainbows, and fertility, as well as the capacity for destruction. While details vary among language groups, one famous narrative comes from the Yolngu people of Arnhem Land (Northern Territory), involving the Wawalik (Wawalag) Sisters and the great python Yurlunggur (Julunggul). The sisters were traveling across the land, naming places and creating waterholes. One sister was pregnant, and as they camped near a sacred well, she gave birth, or according to some versions, she was menstruating. The blood from childbirth (or menstruation) flowed into the water and awoke Yurlunggur, the huge Rainbow Serpent who dwelt there.

Drawn by the scent of blood, Yurlunggur emerged, and in a dramatic moment, swallowed both sisters (and the newborn child) whole. While in the serpent’s belly, the sisters began to sing sacred songs. Their presence inside the serpent and their singing caused Yurlunggur to become torpid and full of power. Eventually, the serpent reemerged and let out the sisters (in some tellings, he regurgitates them, effectively giving them rebirth). The act of devouring and regurgitation is said to have released a flood of creative energy. It established the pattern of initiation rites for the people – the story is re-enacted in male initiation ceremonies where young men “die” (symbolically swallowed by the serpent) and are reborn as initiated adults. Julunggul is often seen as female or androgynous, associated with women’s power (menstruation, childbirth) and also the power that men seek to harness in ceremonies. The Wawalik Sisters, through their experience, bring the knowledge of sacred ritual and the connection to the Rainbow Serpent to their community.

In other regions, the Rainbow Serpent is credited with shaping the land—as it traveled, its winding tracks became rivers and ranges. It often carries a creative and destructive duality: bringing life with water, but punishing those who break taboos. Some groups portray the Rainbow Serpent as male, others as female, or as a pair of serpents. In all cases, it’s tied to fertility of the land and the coming-of-age of people. Notably, in many versions women play key roles, either as victims (like the Wawalik sisters) or as companions. Sometimes a frog or eel-woman holds the water until the serpent releases it, or a female ancestral figure must be appeased.

In Aboriginal traditions, these myths are part of the Dreamtime (Tjukurpa), the time of creation when ancestor beings formed the world and instituted Law. The Rainbow Serpent is a Dreaming that is still revered; its story is sung in cycles that relate to rain ceremonies and initiation.

The Australian Rainbow Serpent myth with the Wawalik Sisters illustrates a potent mix of gender, knowledge, and transformation. The women (sisters) inadvertently trigger the cosmic snake’s action through natural bodily processes, highlighting how women’s reproductive power is intertwined with the sacred. The result – their swallowing and eventual return – establishes crucial cultural knowledge: the cycles of death and rebirth in initiation, and perhaps a warning about respecting sacred sites. The serpent here is an initiator and law-giver, not a deceiver. Its symbolism is rich: rainbows (often seen after rains) connect sky and earth, just as Yurlunggur connects the human and spirit worlds in the rite of passage. Rather than giving or withholding fruit or fire, this serpent mediates life cycles and rainfall. Through the lens of human condition, the Rainbow Serpent stories explain why we have sacred ceremonies, why water is life, and why transgressing sacred law (like taboo times for women at waterholes) can be dangerous. Women’s role is again pivotal – as bearers of life and as figures whose interactions with the serpent bring about the structured spiritual life of the community.

Tāne and Hine: From Clay to the Underworld (Māori, New Zealand)

In the Māori traditions of Aotearoa (New Zealand), the creation of humans and the origin of death are explained through the deeds of the god Tāne and two important women he brought into being: Hine-ahu-one and Hine-titama (who becomes Hine-nui-te-pō). Initially, the world was formed when Sky (Ranginui) and Earth (Papatūānuku) were pushed apart by their children. After separating his parents to let light into the world, Tāne Mahuta (god of forests) set about populating it. He created the first woman, Hine-ahu-one (“Earth-formed Maiden”), out of sacred red clay at Kurawaka (the loins of Mother Earth). He shaped her figure and then breathed life into her. Hine-ahu-one came alive as the first human woman. Tāne then married this first woman (in a sense, his daughter since both descend from Earth) and they had a child, Hine-titama (“Dawn Maiden”).

Hine-titama grew up not knowing her father was also her progenitor. She became Tāne’s wife as well and bore children – thus humans descend from them. One day, Hine-titama asked Tāne who her father was, for she sensed something amiss. When Tāne revealed the truth – that he was both father and husband to her – Hine-titama was overcome with shock and shame. Feeling she could no longer remain in the world of light after this unintentional incest, she fled. She journeyed to the underworld, deciding to reside there. There she transformed into Hine-nui-te-pō (“Great Woman of the Night”), the goddess of death and ruler of the underworld. When Tāne attempted to follow and win her back, Hine-nui-te-pō told him to return to raise their children in the world above. “I will wait for them in the night,” she said, indicating that all her descendants (all humans) would eventually come to her, passing into her care through death.

Hine-nui-te-pō is often depicted as a formidable figure with flaming eyes and teeth of obsidian. In one popular legend, the hero Māui seeks to defeat death by reversing the birth process: he tries to crawl into Hine-nui-te-pō’s body to destroy her from within, entering through her vagina while she sleeps. But the fantail bird laughs, waking her, and she crushes Māui with the obsidian teeth, killing him. Thus mortality became permanent for humans – Māui’s hubris failed and humans could not escape Hine-nui-te-pō’s power.

In Māori mythology, the creation of the first woman from clay by Tāne is very direct: it’s the breath of life (haora) that vivifies her. This theme resonates globally (life from earth, breath from deity). But the uniquely Polynesian twist is the tale of Hine-titama’s self-exile, which explains how death entered the world not as a curse from a trickster, but as a choice made by an ancestor to take on the role of Death for the sake of cosmic order. Hine-nui-te-pō is not evil; she’s described as a kindly if stern grandmother who receives the souls of her descendants. Women in this cycle of stories are central: one is the first human and mother of all, another becomes the guardian of the afterlife.

The serpent or dragon motif is absent in Māori creation, but sometimes Hine-nui-te-pō’s fearsome vagina dentata is likened to a monster’s mouth – in Māui’s failed quest, she is the peril to overcome, analogous in some way to challenges like dragons in other myths.

Tāne and the Hine stories highlight female agency in the establishment of fundamental aspects of human existence. A woman made of earth (Hine-ahu-one) ensures that we are children of the Earth. Her daughter’s moral decision to depart rather than live in shame institutes death as a natural part of life. No external devil or snake causes the fall of man; instead, death is born from a tragic knowledge (incestuous truth) and a woman’s response to it. It adds a poignant layer to the human condition: we die not because we stole something or were tricked, but because a great-grandmother long ago loves us enough to receive us when life ends, taking away the burden of immortality. In Māori thought, this is not a punishment; it is whakapapa – genealogical destiny. And it was set in motion by Hine, a woman whose roles encompass both the beauty of dawn and the mystery of night.

Conclusion: Women, Serpents, and the Dawn of Consciousness

From this world-spanning survey, we see some clear thematic threads. Women in creation myths are overwhelmingly portrayed as essential contributors to humanity’s origin and civilizational knowledge. Whether it’s goddesses like Inanna stealing the arts of civilization for her people, Isis outwitting the sun god to empower Osiris’s just rule, or culture heroes like Mama Ocllo teaching the first women to weave, Changing Woman forming the Navajo clans, and Sky Woman quite literally founding the earth and agriculture – the feminine is a source of life, wisdom, and social order. Even when a female act introduces hardship (Pandora opening the jar, or Eve sharing the fruit), it is inseparable from the acquisition of greater awareness or capability (hope in Pandora’s case, moral knowledge in Eve’s). Female figures often embody a paradoxical blend of nurturer and initiator of change. In the more positive depictions, woman is the first teacher, the one who mediates between humans and the divine (like Nüwa teaching marriage, or Hine-nui-te-pō providing an afterlife). In more ambivalent tales, the woman is a threshold figure whose actions move humans from innocence to experience (Eve, Hine-titama). In almost all cases, without her, the story – and humanity – would not progress.

Serpents and dragon-like creatures appear repeatedly with a dual face: they are symbols of wisdom, life, and continuity in many cultures, yet also can represent chaos or dangerous knowledge. We saw serpents that support creation – e.g. the cosmic serpents like Aido-Hwedo holding up the earth, or the Rainbow Serpent shaping the land and initiating youth – and serpents that steal or block immortality, like the snake in Gilgamesh’s story, or Kāliyya Nāga in some Hindu tales (not covered above) that poison waters until subdued. The Biblical serpent stands out as a villain granting a moral awakening at a steep price, whereas the Feathered Serpent (Quetzalcoatl) is a hero who both creates and civilizes. This shows how cultural context shapes whether the serpent is seen as friend or foe. A snake shedding its skin can mean renewal and wisdom (as in African and Asian lore) or deception and the loss of innocence (as in Semitic lore). Importantly, serpents are very often guardians of sacred things – Enki’s serpent of the Deep, Python at Delphi in Greek myth, or the rainbow snake guarding water – and sometimes the challengers or tricksters who force humans to adapt. In our survey, whenever serpents entered the plot, they signaled a turning point: gaining knowledge (Eden), ensuring balance (Mawu’s serpent), conferring initiation (Rainbow Serpent), or preventing immortality (Gilgamesh’s snake). In each case, humanity’s path was altered through contact with this liminal creature.

Crucially, these myths each offer answers to universal questions: “Why are we the way we are? How did we learn to live as humans, and why must we suffer, die, but also hope and prosper?” The answers differ: for the Sumerians, knowledge is a gift won by a goddess and mortality is simply the way of things; for the Hebrews, knowledge is tangled with disobedience and mortality is penalty; for the Greeks, technological fire elevates us even as Pandora’s curiosity afflicts us. In the Indian Upanishad, our selfhood is born of a primordial split – we are literally the consciousness of the universe, divided, seeking reunion. In the Navajo and Inca stories, humans weren’t fallen at all – just untutored until a holy person showed the way. The presence of death is explained tenderly by the Māori as the result of a great-grandmother’s choice, whereas in Zoroastrian and Iroquois accounts it’s due to malevolent forces or a fateful twin. Despite these differences, a common theme emerges: humanity always comes into a greater fullness of life through a pivotal event, often involving a woman’s action (creative or transgressive) and/or an encounter with a serpent/dragon (wisdom or danger).

Many of these myths also emphasize that with the gifts of civilization or consciousness comes a responsibility or cost. Civilization is sacred – writing, farming, weaving, law are often taught by gods and must be honored. Self-awareness is double-edged – it gives us godlike powers (to understand, to create) and godlike troubles (worry, regret, knowledge of death). The role of women as first ancestress or teacher often sacralizes women’s societal roles (mothers, priestesses, keepers of tradition), while the recurring serpents suggest that humanity’s road to wisdom is never without risk or complexity.

In sum, the world’s creation and origin myths form a tapestry where:

Women appear as bringers of life and knowledge, from the bold Inanna and compassionate Changing Woman to the curious Eve and devoted Sky Woman.

Serpents/Dragons serve as keepers of profound secrets – sometimes sharing them, sometimes barring them – be it the serpent in Eden offering knowledge with a sting, or the rainbow snake initiating youths into adulthood.

Human consciousness & civilization are depicted not as trivial accidents, but as the results of divine intention, cosmic drama, or brave deeds. We are meant to have knowledge (almost every myth shows humans eventually receiving the knowledge they need), but we also inherit toil, mortality, or moral obligation as part of the package.

These stories, though varied in origin – from deserts to jungles, from ancient cities to nomadic camps – all grapple with what it means to be human. By casting primordial women and powerful serpents in prominent roles, they acknowledge that the emergence of our humanity is deeply tied to birth and sex, wisdom and temptation, earth and animal, courage and curiosity. Each narrative provided early societies with a sense of identity and an explanation for why life contains both order and struggle, knowledge and mystery. And in all of them, the dawn of human self-awareness is not a mundane event but a sacred, pivotal transformation – one that traditions around the world have long preserved in mythic memory.

Though if you do want to read more, other good sources include: Wikipedia’s List of Creation Myths, Leeming’s Dictionary of Creation Myths, and Narby’s Cosmic Serpent (for the snake angle).