When did recursion evolve?

Or, Sodomy in the Uncanny Valley

After millennia of debate on the origins of consciousness, experts still put forth start dates spanning five orders of magnitude. This post will highlight some of those attempts, relate them to recursion, and give a sense of the tradeoffs for each date. These include proximity to Nazis, the inner life of chickens, and sodomy in the uncanny valley. Stay tuned!

Researchers admit a broad bias for distant dates. It’s only fair I disclose my own preference for recent dates. I think it’s possible that the evolution of recursion has been preserved in creation myths. Self-awareness is the ability we can most confidently link to recursion; its emergence would make for quite the story. Comparative mythologists are unsure how long a myth can last, but some hazard guesses in the 100,000-year range. Strikingly, that is within the mainstream view of when recursion evolved.

The previous post covered how recursion is required for self-awareness, likely required for language, and possibly even for subjectivity itself.

200,000,000+ years ago

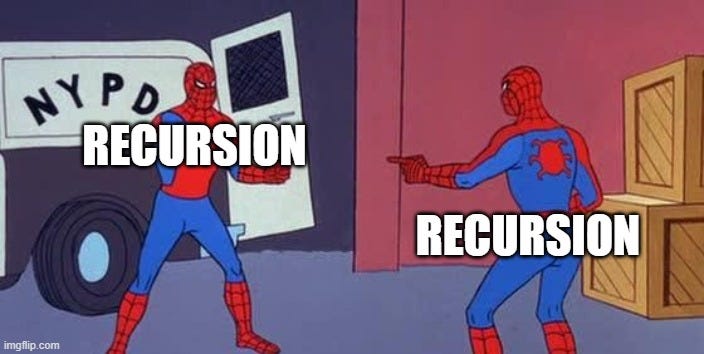

The earliest dates have to do with whether animals have subjective experiences, and if this requires recursion. Take for example the paper Consciousness as recursive, spatiotemporal self-location. It argues that this ability goes back to crustaceans and that what makes humans special is “a more fully evolved level of conscious awareness” which includes “metacognitive capacities…introspection, abstract reasoning, and elaborate planning”. However, “the more fully evolved form of consciousness should be seen not as an expanded, upgraded or changed form of self-consciousness, but a case of subjective self-awareness augmented by an entirely different, separate and independent set of cognitive mechanisms.”

Did you get that? The article is arguing that subjectivity is caused by recursion. Human self-awareness is the thing we are most sure entails recursion. And yet the paper maintains the two are caused by an “entirely different, separate and independent set of cognitive mechanisms.” If they are the same, one risks accepting the problematic position of Descartes, that animals don’t have subjectivity.

This tension between recursions is apparent in the work of Nicholas Humphrey, who has written 10 books on the subject of consciousness. His most recent—Sentience: The Invention of Consciousness—begins “We feel, therefore we are”. Like Descartes, but more empathic. As an emeritus professor, he is willing to bite the bullet on the recent date this emerged.

Taking all this into account, I’m led to a surprising – and possibly unwelcome – conclusion. I believe sentience must be a rather recent evolutionary innovation. By far the majority of animals on Earth have neither the brains nor the use for it. To stick my neck out, I’ll be more specific: I suspect that sentience may not have arrived until the evolution of warm-blooded animals, mammals and birds, around 200 million years ago.

200 million years! This is built up as if it’s something to be embarrassed about for recency. There is enormous pressure for academics to be as inclusive as possible when doling out recursion. Everything is a hostage situation where you may get shut down by the union of concerned bees or octopi if you hint they are wanting. I jest, of course, but still much prefer Werner Herzog on chickens:

And lest you think I am taking Professor Humphrey out of context, he explicitly talks about sentience being implemented via recursion and attractor networks. His conclusions are based on several considerations (warm blood, for example), including six behavioral criteria. Does an animal:

Have a robust sense of self, centred on sensations?

Engage in self-pleasuring activities – be it listening to music or masturbation?

Have notions of ‘I’ and ‘you’?

Carry their sense of their own identity forward?

Attribute selfhood to others?

Lend out their minds so as to understand others’ feelings?

Paraphrasing Herzog: “You have to do yourself a favor. Try looking at a chicken in the eye with great intensity. The enormity of the flat-brained stupidity looking back at you is overwhelming.” And yet Humphrey asks us to ascribe a “robust sense of self” to poultry. What is sentience if chickens too “lend out their minds so as to understand others’ feelings”? And how is it useful if chickens have it but octopi do not? Undercutting the grand criteria, Humphrey reasons: “Given the life-tasks that non sentient animals and machines have been designed to accomplish, we can assume that phenomenal blindness leaves them none the worse off.” Gosh, I guess being alive isn’t all it’s cracked up to be.

Notice that the list does not include any hard criterion of recursion1. I have to admit it is a clever switch. Instead of identifying evidence of recursion when trying to demonstrate recursion, one can instead ask whether a species masturbates. It is when dogs are in heat, humping the couch, that we most clearly see ourselves.

This highlights the supposedly insurmountable chasm between recursion for subjectivity and every other recursion. Think of it this way, flowering plants evolved 130,000,000 years ago. Since then bees, ants, butterflies, fruits, and every flower you have ever seen have all blossomed into their myriad forms. If recursion has been around for 200,000,000 years, why wasn’t it co-opted to do anything useful? For 99.9% of the history of recursion, it laid low, granting chickens the dignity of “I” but nothing else. Then, all at once in humans, an entire array of recursive abilities burst forth which allowed us to conquer the world. Could be, but in the words of Kepler, “Nature uses as little as possible of anything”. If recursion was there, I think nature would have found a way to put it to use.

Finally, one of the criteria is to have notions of ‘I’ and ‘you’. Interestingly, the distribution of pronouns is consistent with them spreading more recently than the Out of Africa event. I think that implies their recent invention, but of course we look through a glass darkly.

2,000,000+ years ago (Sodomy in the Uncanny Valley)

Language and Modern Human Origins argues “No data are found to support linking the origin of modern humans with the origin of complex language… Instead, there appears to be archaeological and paleontological evidence for complex language capabilities beginning much earlier, with the evolution of the genus Homo.”

For reference, this is Homo Habilis which lived about two million years ago.

Robert Proctor is a historian of science specializing in how forces like the tobacco industry or WWII shape the interpretation of data. He also studies human origins at Stanford. When asked directly when we evolved Proctor punts:

That is exactly the question we need to problematize. It’s what I call the Ghandi question. When asked “what do you think of western civilization?” he said “it would be a good idea”. So, when did humans evolve? Well not yet… What’s happened in the last 50 or 60 years—which I think is a good thing, intellectually—is that we’ve smeared out humanness to mean many different things. It’s not just tool use or upright posture…It’s an interesting question because after WWII as a result of Nazism no one wanted to be the one to say that this particular fossil we’ve just found was anything less than fully human so there’s a projection of humanness arbitrarily back into the past so that even these little monkey-like creatures rhombopithicus were being declared to have folkways and mores and language which is ridiculous. No one wanted to be the one to say that Neanderthals were anything less than fully human. It’s a very interesting question; human origins is very much an identity quest. When we became us sort of begs the question, "What are we?”

What he is describing is a taboo within science. Nazis argued that Aryans and healthy people were better, and slaughtered those that were not. As a response, science is now extremely reticent to ask who we are and where we came from. If there is a standard for what it means to be human, that could once again fuel genocide. So the thinking goes.

I don’t think that follows! Communist belief in equality resulted in many deaths (though the relationship may not be as direct), as does American consumerism. Values are by nature dangerous. As is abstaining from them, particularly if the default replacement is nihilistic ennui. There is a reason so many cultures teach that we should first know ourselves. We must know; one cannot ignore it and live. Every story is to that effect. And I truly believe our identity may be a thing of beauty, with the power to unite. See for example my first post on the inner voice, Consequences of Conscience. My theory is that “I” was forged out of evolutionary pressure to live the Golden Rule. No man is an island, for society is baked into self.

You can see how recursion clashes with this taboo. It is a strong claim! We have an inner life and language because of this mathematical principle. Humanness may not be smeared over many definitions or millions of years. We might have to grapple with our own beginnings.

So, researchers tend to push our origins as far back as they can get each other to believe. Nevertheless, Proctor provides an intuition pump to frame the question.

Proctor: “There’s the problem that I call sodomy in the uncanny valley. Which is: how long ago would you be willing to date someone?”

Lex Fridman: “A date or a one night stand?”

Proctor: “Let’s say, be the mother of your children.”

Fridman: “That’s a lot of commitment”

Proctor then asks: “10 million years ago? 5 million? 3 million?”. The exercise is designed to be provocative and yet he still offers dates from before we split from chimps. He can speak of the bias, but not deny it. Pictured below is Lucy, a relative 3 million years in the past. Would you take her to wife?

The paper on language origins makes arguments in line with Proctor’s explanation. It proposes that two major biases led to the confused link between language and Homo Sapiens: “linguicentrism” and “Eurocentrism”. In an archeological sense, Eurocentrism refers to the question of why Homo Sapiens so readily replaced Neanderthals. Might we have had some cognitive advantage? The author finds this question overrated. It is hard not to read the colloquial sense of “you care more about Europeans” as well. The paper argues that, if we took the archeological record in Africa more seriously, we would see evidence of the human condition, including complex language, deep in the past. It has a sort of god of the gaps quality; recursion is everywhere we can’t properly test it. Homo Habilis could learn the Queen’s English if only given the chance.

The linguist Dan Everette also argues language emerged at this time. But his claim is more measured. He does not think this language was recursive, or indeed that language has to be now.

Others do not cede so much ground and see recursion in the tools that were produced at this time. The relationship between recursion and tool-making is how one organizes a set of tasks. To make a hand-ax one must make a blade and handle, and then combine them. “Make a blade” can then be broken up into many steps, as can the other two steps. But pretty much any task can be parsed thus. Spiders must first weave the supporting lines of their web before placing the spiral. Winter migration or bird song, too, is hierarchical. In robotics, even grabbing a Coke from the fridge is treated as a hierarchical problem.

It’s hard to put hand-ax construction firmly in the “human special sauce” category and not also pick up a lot of animal (and Neanderthal) behavior, as we shall see in the next section. If recursion evolved 2,000,000 years ago it is only a small part of what makes Homo Sapiens special.

400,000 - 200,000 years ago

In The Recursive Mind: The Origins of Human Language, Thought, and Civilization, Michael Corballis delves into the transformative power of recursion on our species. As a psychologist and linguist, Corballis has devoted considerable thought to the profound impact recursion has had on our mental landscape. In his book, he shares an intriguing question that Jared Diamond encountered while conducting fieldwork in Papua New Guinea:

“Why is it that you white people developed so much cargo and brought it to New Guinea, but we black people had little cargo of our own?”

To which Corballis adds:

The vast differences in cargo between the people of New Guinea and those of modern European, North American, or Australasian society can only reinforce my belief that the essence of humanity is not the things we make, but rather the way we think. Our recursive understanding of each other, and our recursive ability to tell stories, whether fictional or autobiographical, is what truly sets us apart from other species, but aligns us with our fellow humans, of whatever race or culture.

I agree! We are the stories we tell, not our cargo. I wish Corballis would use the same standard to date when we became human. Instead, he defines our origins by reference to tools—cargo. Quoting at some length:

The Acheulian [Stone Age tool] industry remained fairly static for about 1.5 million years, and seems to have persisted in at least one human site dating from only 125,000 years ago. Nevertheless at some sites there was an acceleration of technological invention from around 300,000 to 400,000 years ago, when the Acheulian industry gave way to the more versatile Levallois technology.

…

Tools are of course important to the human story, but there is little evidence that they were decisive in creating the human mind. To be sure, recursive elements were evident in tools from half a million or so years ago, but a truly manufactured world did not really emerge until after the appearance of Homo sapiens, and varies widely between different cultures. My guess is that recursive thought probably evolved in social interaction and communication before it was evident in the material creations of our forebears. The recursiveness and generativity of technology, and of such modern artifacts as mathematics, computers, machines, cities, art, and music, probably owe their origins to the complexities of social interaction and storytelling, rather than to the crafting of tools.

…

It is generally reckoned that the species Homo sapiens who emerged some 170,000 years ago was “anatomically modern”—human at last. This was a large-brained species equipped with the intelligence and social understanding of modern humans. If you were to snatch an infant from that time, and raise that infant in the present- day Western world, he or she would probably adapt as well as any modern-born person to the exigencies of modern life, whether as stockbroker, ballerina, modern-day hunter-gatherer, university professor, or used-car salesperson. The Pleistocene had gradually shaped recursive modes of thought that allowed complex theory of mind and mental time travel, and allowed for the relaying of memories, plans, and stories for the betterment of both the society and the individual.

In summary, he sees evidence for recursion in tool-making 400,000 years ago and assumes that this must have been preceded by recursive communication, even though evidence of stories or a manufactured world does not emerge for another 360,000 years. He then confidently says that someone from 170,000 years ago, when our skeletons took their modern gracile form, could become a professor or salesperson if they were raised in a modern environment.

This line of reasoning significantly downgrades the role of recursion in the human story. It cannot, then, be used to explain why humans outcompeted the Neanderthals. In fact, the Levallois technology Corballis uses to date the emergence of recursion in humans is primarily a Neanderthal technology.

Further, there’s only a fine line separating this level of tool-building from what animals make. Corballis concedes that crows build tools as sophisticated as the previous tool industry, the Acheulian.

Finally, this is the Sapient Paradox on steroids. If we had recursion for half a million years, why so few signs of inner life? If innovating tools is the mark of recursion, then why was the Levallois static for 100,000 years? Direct evidence of recursion in narrative art coincides with the start of continuous innovations in tool-making. To his credit, Corballis discusses the limitations of his model:

Homo sapiens emerged in Africa about halfway through the period known as the Middle Stone Age, which began around 300,000 years ago and ended around 50,000 years ago. Early sapiens may have been anatomically modern, but in terms of culture and technology was probably not greatly distinguishable from other large-brained members of the genus Homo. These included the Neandertals, who died out in Europe some 30,000 years ago, apparently eclipsed by the arrival, some 20,000 years earlier, of our own predatory species.

…

The African record prior to the exodus certainly suggests the beginnings of modernity, although the development of technology and cultural complexity seems relatively meager compared with what was to come in the Upper Paleolithic, or Late Stone Age, which is generally reckoned to have ranged from some 40,000 years ago to 12,000 years ago.

Since Corballis’s book, there has been compelling work on the use of ochre pigments which go back as far as 500,000 BP in Africa and are commonly used after 160,000 BP. It may have been used for body ornamentation and ritual, so it’s not just tools that could imply recursion at this date. And there is lots of room for uncertainty. If art was made of wood, for example, it would not be preserved. But still, it’s hard to be confident that all the forms of recursion go this far back. It’s not clear to me why some researchers are sure someone from this time period could live now as an accountant.

Below is a plot from the paper Genetic timeline of human brain and cognitive traits which analyzes when new mutations entered the human gene pool. Notice the dramatic surge that happens well after 200,000 BP. This influx of new genetic code aligns with the emergence of much more sophisticated technology, including art. Many of the genes are known to be expressed in the brain and be related to psychiatric traits. We should be open to this being part of the human story.

Continued in part two.

This is par for the course in animal consciousness literature. For example see the 2023 paper Profiles of animal consciousness: A species-sensitive, two-tier account to quality and distribution. It puts forth a 10-dimension system of animal consciousness. The paper does not even mention recursion. Considering how many disciplines believe that recursion is involved, it seems that one should at least justify leaving it out of the top-10 list.