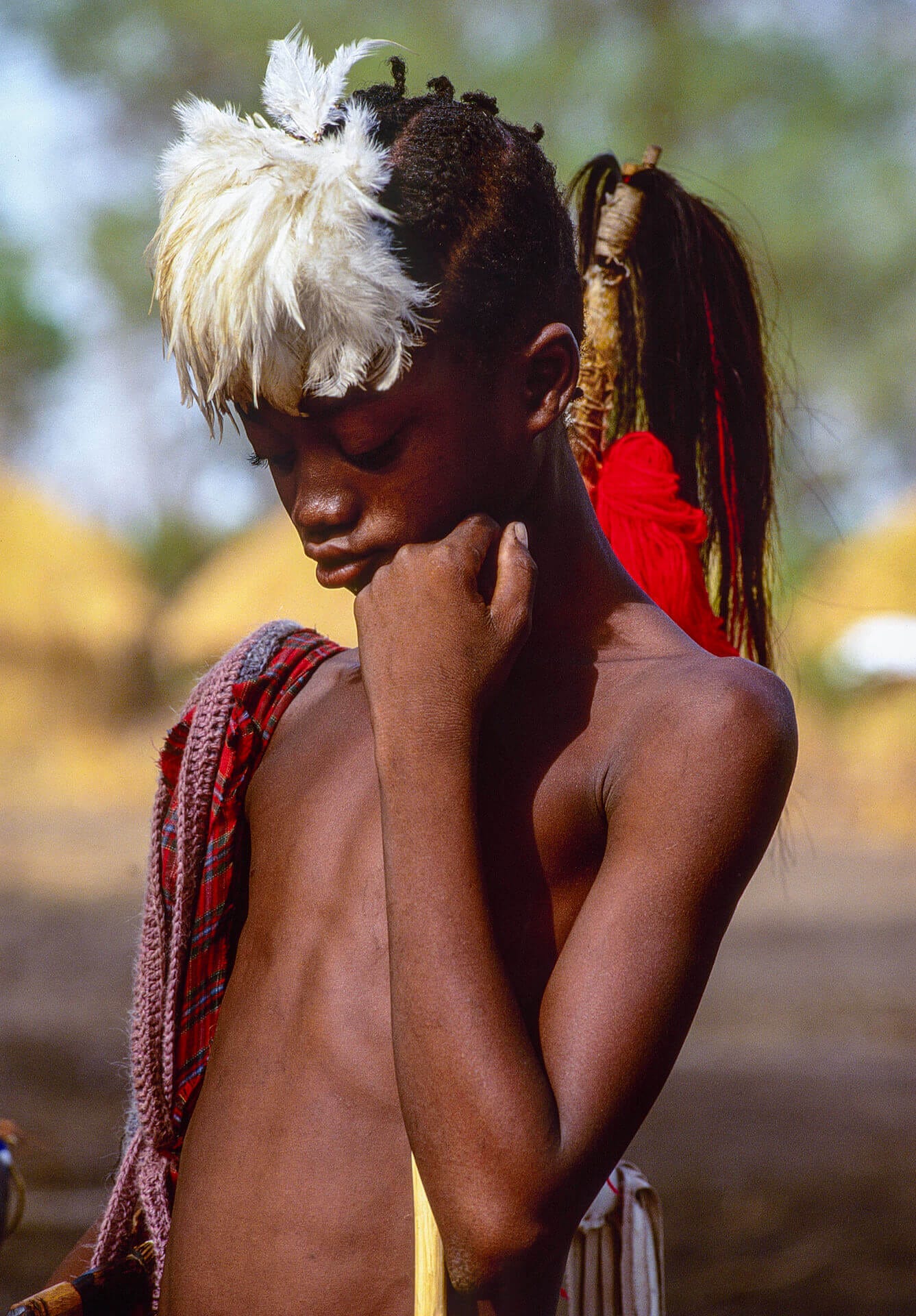

Genesis in Togo

Wherein God grants the serpent medicine with which to bite man

In 1921, Leo Frobenius reported the creation myth of a Bassari tribe in Northern Togo:

“Unumbotte made a human being. Its name was Man. Unumbotte next made an antelope, named Antelope. Unumbotte made a snake, named Snake. At the time these three were made there were no trees but one, a palm. Nor had the earth been pounded smooth. All three were sitting on the rough ground, and Unumbotte said to them: "The earth has not yet been pounded. You must pound the ground smooth where you are sitting." Unumbotte gave them seeds of all kinds, and said: "Go plant these." Then Unumbotte went away.

Unumbotte came back. He saw that the three had not yet pounded the earth. They had, however, planted the seeds. One of the seeds had sprouted and grown. It was a tree. It had grown tall and was bearing fruit, red fruit. Every seven days Unumbotte would return and pluck one of the red fruits.

One day Snake said: "We too should eat these fruits. Why must we go hungry?" Antelope said: "But we don't know anything about this fruit." Then Man and his wife took some of the fruit and ate it. Unumbotte came down from the sky and asked: "Who ate the fruit?" They answered: "We did." Unumbotte asked: "Who told you that you could eat that fruit?" They replied: "Snake did." Unumbotte asked: "Why did you listen to Snake?" They said: "We were hungry." Unumbotte questioned Antelope: "Are you hungry, too?" Antelope said: "Yes, I get hungry. I like to eat grass." Since then, Antelope has lived in the wild, eating grass.

Unumbotte then gave sorghum to Man, also yams and millet. And the people gathered in eating groups that would always eat from the same bowl, never the bowls of the other groups. It was from this that differences in language arose. And ever since then, the people have ruled the land.

But Snake was given by Unumbotte a medicine with which to bite people.

…

It is important to know that as far as we know there has been no penetration of missionary influence to the Bassari. . . . Many Bassari knew the tale, and it was always described to me as a piece of the old tribal heritage. I have heard it told by a number of people at various times and have never been able to detect any significant variations. I have, therefore, to reject absolutely the suggestion that a recent missionary influence may lie behind this tale.” 1

The line about the snake’s bite being medicine is particularly interesting, given snake venom has been used ritually to reach ecstatic states—a fact I only discovered after musing Genesis could be read as Eve initiating Adam to a psychedelic snake-venom cult. In all seriousness, it’s a strange line. Why is God giving snakes a medicinal bite part of this culture’s answer to how humans came to be? See also the San Bushmen of South Africa, who speak of an ur-shaman who established their trance dance, which includes ground-up snake powder that would cause celebrants to enter altered states of consciousness2.

(Post-publish note: Michael Witzel translated the same line, “But Snake was given by Unumbotte a medicine (Njojo) so that it would bite people.” I emailed him about the discrepancy, and he said it’s due to Campbell not being a native German speaker. So, the venom stuff is significantly less interesting.)

Putting stoned-snake theories aside, the similarities with Genesis are such that psychic unity cannot explain this myth; there must be a (pre-)historic connection. Even given Frobenius’s judgment that missionaries weren’t involved, one can’t completely rule that out. Still, what would it look like if this were part of an earlier cultural package that spread to Sub-Saharan Africa?

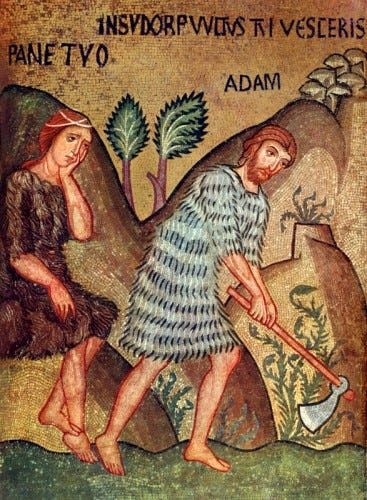

By the sweat of your brow you will eat

The origins of agriculture, of which both myths are concerned, provide a clue. For the first 190,000 years, anatomically modern humans were hunters and gatherers. About 10,000 years ago, that began to change as plants were domesticated in the Near East and then all over the world. Traditionally, this has been treated as an independent phenomenon.

“In the spring of 2011, 25 scholars with a central interest in domestication representing the fields of genetics, archaeobotany, zooarchaeology, geoarchaeology, and archaeology met at the National Evolutionary Synthesis Center to discuss recent domestication research progress and identify challenges for the future. In this introduction to the resulting Special Feature, we present the state of the art in the field…” (source)

What strikes me is that they could get 25 people with diverse research agendas to agree: “At least 11 regions of the Old and New World were involved as independent centers of origin, encompassing geographically isolated regions on most continents, but several more have been suggested.”

The map indicates farming was invented independently in Northwest Africa in the mid-Holocene and, from there, spread south to the rest of Africa with the Bantu expansion. As with many sensitive social questions, genetics is having the last laugh. In 2023, Nature published an analysis of ancient genomes: Northwest African Neolithic initiated by migration from Iberia and Levant. It found agriculture, domesticated animals, pottery, and a host of new tools were introduced by migrants. The first came from Europe about 7,000 years ago, then a group from the Levant starting at least 4,000 years ago. Now, I want to be clear that the samples are from what is now Morocco to the North. So we’ll have to wait to see what future genetic research reveals about the agricultural revolution in Senegal, the primary home of the Bassari. However, it always seemed strange that after 190,000 years, a dozen civilizations had the same idea all at once. Diffusion is a more parsimonious answer. And the introduction of Neolithic technology would have also brought new myths.

This isn’t exactly an argument that the Bassari Genesis entered Africa 4,000 years ago. This is merely a plausible path of cultural diffusion, which is usually ignored. For example, Michael Witzel compares this myth to Genesis and the Popol Voh (Mayan), arguing that the similarities are best explained by a root myth 100,000-160,000 years old that spread with the Out of Africa migration. Much of his argument hinges on Sub-Saharan Africa being hermetically sealed from outside influence in the last 10,000 years, a view that defies common sense and crumbles at contact with archeogenetics.

The Fall of Man

One mark against the Bassari story being a pre-Christian cousin to Genesis is the retention of so many details, down to a tempter snake and God returning on the seventh day. More modifications are expected after millennia of transmission, and further, if the myth accompanied the introduction of the Neolithic lifestyle, by now myriad versions would be scattered over a large area. On that score, no myths are as close a match as the Bassari tale. However, the idea that the human condition is due to some accident or disobedience is widespread in ways that belie a phylogenetic connection, at least regionally. There are such myths worldwide, but the myths in Africa are more similar to one another than, say, stories of a Fall in Australia or Mesoamerica. The entry on The Fall in the Encyclopedia of Religion tells us:

“The fall may also result from human failings. Once again, the most important documentation is found in sub-Saharan Africa. A Maasai myth known in both Africa and Madagascar tells of a package that humans were given by God but forbidden to open; driven by curiosity, they opened it and let loose sickness and death. The divine prohibition takes other forms in other traditions. In a Pygmy story of central Africa, it is against looking at something; in a story of the Luba in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, it forbids the eating of certain fruits; in a Lozi myth found in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Malawi, it prohibits the taking of wild game.

Sometimes humanity's fault is best understood anthropologically, as in myths describing theft or lying, or those that stress lack of charity, or the race's capacity for domestic violence, as in a Chiga myth from Uganda. The curiosity of the primordial couple who aspire to the secrets of the gods is a frequent mythical theme in Africa, where myths of the fall also emphasize the cohesiveness of individual and group.”3

The Proto-Indo-European reconstruction for water is *wódr̥, not so far from the English pronunciation 6,000 years later. The path to the French, however, is tortuous: PIE *wódr̥ → Latin “aqua” → Old French “ewe” → Modern French “eau.” So it is with the evolution of myths. Some cultures will happen to retain something close to the original, while many other branches mutate. Still, general themes will be visible when one looks at the whole.

Conclusion

But Snake was given by Unumbotte a medicine with which to bite people.

The case against ancient diffusion is the fact Muslims or Christians could have made inroads that Frobenius didn’t detect. The Bassari could have syncretized the Biblical creation story and not much else. For the contact to be ancient, it would not be so targeted as to just show up among one tribe. There are millions of Christians living in Africa today who would love to show that they are part of a lost tribe of Israel. And there is ongoing, well-funded Christian anthropological research. If other indigenous creation myths were similar to Genesis, they would be well documented.

The case for ancient diffusion is that obvious parallels are well documented. The Fall of Man is widespread in African creation myths, and various tribes that have claimed to be lost Israelites have been vindicated by genetics, such as the Lemba of Zimbabwe (though their journey was much after the advent of the Neolithic). There is precedence for the prehistoric spread of people and ideas into the heart of Africa. However, academic theorizing about links between Neolithization in Africa and Eurasia has been hampered by association with the Hamitic hypothesis, the idea that Africans are the descendants of the cursed son of Noah, Ham. Diffusion is, as always, problematic when it’s from Eurasia into any other continent.

If this curious case were to be studied, it would be fruitful to return today and record the current creation myth and the degree of Christian influence in their traditions more broadly. Genetics, too, could shed a light. As for mythologists’ gut feeling, both Campbell and Witzel treat the myth as indigenous.

Our current era, the Holocene, means “wholly new” because it coincided with the rise of human civilization. The default assumption in many sciences is an Ages of Man myth. For 190,000 years, man lived as a hunter and gatherer, barely producing art. Then, independently, the Neolithic package was invented worldwide starting about 10,000 years ago. It beggars belief.

I think the world’s cultures are intertwined in ways that have been ignored. Other than the incredible coincidence of a global cultural transformation in the Holocene, the strongest evidence may be the bullroarer, a sacred instrument that is used in strikingly similar ways by mystery cults around the world. Or, if you prefer another article about a strange myth featuring Snake enlightenment and medicine, you may enjoy:

Secrets of the Snake King

This article is a change of pace. Instead of endless footnotes and statistical arguments, I’ll let Anatolian folklore do the talking. The most obvious rejoinder to the snake-venom-as-entheogen hypothesis is the snake detection hypothesis. That is, snakes don’t appear in myths because their venom was a shamanic compound in prehistory, but rather because …

Joseph Campbell supplies this translation in his Historical Atlas of World Mythology. The original German is from Leo Frobenius, Volksdichtungen aus Oberguinea, vol. 1, Fabuleien Dreir Völker (Jena, Germany: Eugen Diederichs, 1924), pp. 75-76.

The Bushmen’s creator, Cagn, who “caused all things to appear, and to be made,” introduced the trance dance:

“Cagn gave us the song of this dance and told us to dance it, and people would die from it, and he would give charms to raise them again. It is a circular dance of men and women, following each other, and it is danced all night. Some fall down; some become as if mad and sick; blood runs from the noses of others whose charms are weak, and they eat charm medicine, in which there is burnt snake powder.” ~Qing, a Bushmen man from the Drakensberg, interviewed in 1873 by Joseph Orpen

Notably, the Bassari and San both use the bullroarer in ritual settings, which has been widely argued to stem from a very early mystery cult. Tying this in with Genesis, bullroarers are found 10,500-8,400 BP in Israel and even earlier in Northern Mesopotamia, where agriculture was invented, which is addressed in both versions of Genesis. This suggests a neolithic package—including sedentism, creation myths, and bullroarer cults—could have spread into Africa.

The whole entry is jarringly perspicacious for an online encyclopedia until you realize the author: “Julien Ries (19 April 1920 – 23 February 2013) was a Belgian religious historian, titular archbishop and cardinal of the Catholic Church. Prior to his death, Ries was described as "the greatest living religious scholar."”

Interesting piece. Do you have any more insight into the way that the Bassari use this word 'medicine'? Do we know what word that is a translation of? It just seems like putting a lot of weight on an unknown the way that it is presented.

e.g. https://theconversation.com/aboriginal-australias-smash-hit-that-went-viral-112615

We see often view the past via a parochial lens put in place by city or courtly sophisticates dumping on the hicks, the pagans, the heathens, who they forbid from moving (enserfment and slavery) and then they blame the victim for the induced stupidity and bad education.