The Bullroarer: a history of man's most sacred ritual object

Mystery cults worldwide say the instrument is the voice of god, once belonged to women, was stolen by men, and use it to turn boys into men through a process of death and rebirth

“No ethnomusicologist, I think, would stand for plurigenesis as regards the bull-roarers, which even in decorative detail are often alike and are used for the same purpose wherever and whenever found.” ~Jaap Kunst, 1960

The bullroarer doesn’t look like much. Just a slat of wood or bone attached to a string and then spun to produce a “roar.”1 But to study the bullroarer is to gaze at the history of man, from the beginnings of religious expression in the Ice Age to the mystery cults of the ancient Greeks and primitive cannibals alike2.

This is sufficient reason to engage, but it also gives us a view of the history of anthropology. The field was founded as the scientific inquiry into who we are and where we came from. In the 19th and 20th centuries, a central question was whether far-flung cultures were connected deep in the past or, rather, if their similarities were due to the “psychic unity of mankind.” The bullroarer was a prime artifact in this debate, as it was studied in over 100 separate cultures all over the world by researchers of every ideological stripe. There was—and is—agreement that it is used in strikingly similar ways. Around the world, the bullroarer is called the voice of god or is cognate with the name of the first ancestor or simply “soul.” It’s said to be invented by women who are now forbidden to see or hear it, under pain of death. Or, as tends to be true in more complex societies, it is remembered as spiritually significant in myth but has become secularized and is used only as a child’s toy.

Despite all this, the bullroarer has largely been forgotten. The dictionary defines primitive as “relating to, denoting, or preserving the character of an early stage in the evolutionary or historical development of something.” Animals don’t have language or creation myths, so at some point, humans must have lived in a primitive culture—the first people to grapple with their mortality, abstract ideas, and the spirit world. The charter of Anthropology was to understand those first forays into the human condition and how those foundational ideas progressed into the myriad cultures today. In the last several decades, anthropologists have abdicated this search because of how problematic the ideas of progress and primitive are to the prevailing ethos. If societies can progress, does that mean some are better than others? Easier to look away than try to explain the bullroarer, who we are, or where we came from.

My answer to the 100,000-year gap between modern humans and modern human culture is that fundamental psycho-cultural ideas like “I am” or god could have spread worldwide about 15,000 years ago. Big if true, I know. However, researching this hypothesis led me to a curious debate, spanning a century and still raging. The most readily available information on cultural diffusion is produced by those seeking Atlantis or the like. Their evidence is typically something like the “manbags” associated with civilization-bringers and carved into the pillars at Gobekli Tepe, temples in Sumeria, and pyramids in Meso-America.

Now, this isn’t not evidence. But it’s quite soft. Bags are useful, and the physics of holding something in your hand suggests a certain form. That a bag is often present in world-founding myths is maybe the 100th most surprising finding in comparative mythology. Still, theories of lost world-spanning civilizations generate enormous interest. Graham Hancock, the most successful of such theorists, has appeared 12 times on the Joe Rogan Experience, and his Netflix special, Ancient Apocalypse, was recently renewed for a second season. There is a cottage industry devoted to detailing links between far-flung myths and megaliths, yet somehow they rarely mention the bullroarer, the best evidence of cultural diffusion.

Prehistoric links between civilizations have been studied for over a century by hundreds (thousands?) of archeologists, anthropologists, linguists, geneticists, and comparative mythologists of all ideological stripes. Yes, the academy in 2024 doesn’t like to discuss diffusion, but this is a fairly new phenomenon. In the past, many academics argued the bullroarer spread with the beginning of fully human culture (or at least fully developed mystery cults). Their research is still available if largely forgotten. It makes sense that this would be ignored by current anthropologists, who want nothing to do with beginnings as that requires discussing “primitive.” However, it’s a totally unforced error that the Atlantis consortium doesn’t lean into the bullroarer, learn its ways, and press the issue. It’s the most compelling case for a connection among the “ancients” worldwide, and there are hundreds of attestations, including in trendy contexts like Göbekli Tepe and the Eleusinian Mysteries. As far as research goes, it’s a slow pitch down the middle, and they don’t even take a swing.

I organize this study chronologically because the story is as much about the researchers as the bullroarer itself. This means the article lives up to its name; it’s more detail than many readers need. Skimming may suffice (I highlight the most important entries in the Outline). I err on the side of too much information in order to make this resource widely available. No other such collection exists, and certainly not online and in English. In my search, it was only late that I happened upon the best current treatment of the bullroarer in The Domesticated Penis: How Womanhood Has Shaped Manhood. Most of the chapter, “The Cultural Penis: Diversity in Phallic Symbolisms,” concerns the bullroarer. But you can see how a student of the bullroarer would miss this text, given the chapter and title names indicate nothing about the instrument. It’s a sort of metaphor for anthropology. Grand theories of human origins can be discussed if tucked away under layers of psychoanalytic feminism.

The quest to understand our origins is a fundamental human drive. I believe past generations of anthropologists were right, and the bullroarer is an important piece of that puzzle. This article presents their research with some commentary.

Summary and General Argument

“Passing eastward across Siberia into America, as well as southeastwardly to Australia, shamanism traveled as but one element of a living compound that included—besides the x-ray style of animal painting and engraving, the atlatl, and the bullroarer—an elaborate complex of social regulations, ceremonials, and associated mythological ideas, which scholars have designated by the very broad term totemism.” ~Joseph Campbell, Historical Atlas of World Mythology, 1983

A few facts about the bullroarer have been established for over a century. From Africa to Australia to the Americas, it is:

Used in male initiation ceremonies of death and rebirth

Said to be the voice of god

Said to have been originally invented by women but was stolen by men near the beginning of culture when they took control of the mystery cult. Often, women are now banned from seeing it or learning the associated mysteries, under pain of death

These practices aren’t universal, but they are common themes. Even tribes that don’t treat the bullroarer as sacred often did at some earlier time.

Mystery cults teach initiates about their place in the universe, the nature of life and death, and the history of humanity. In the 19th century, the first European anthropologists knew the bullroarer as a relic from the Greek mystery cults of antiquity. The Eleusinian Mysteries included an ecstatic procession known as Bacchoi. This celebrated the dismemberment of Dionysus by the Titans, who lured him to his death using a bullroarer and a snake (among other implements). Maenads, the female followers of Dionysus, are said to have reenacted this moment. They wore snakes in their hair and, in ecstatic climax, would tear a live bull (the symbol of Dionysus) to pieces with their bare hands, feasting on its raw flesh. (Some argue this is a precursor of the bread and wine that become the flesh and blood of God in the Christian sacrament.)

When anthropologists started collecting data outside Europe, they found the bullroarer at the center of mystery cults worldwide, documented in more than 100 tribes, especially in Australia, Papua New Guinea, North and South America, Melanesia, and Africa. The use transcends the agriculturalist vs hunter-gatherer divide. In Africa, it is known to the Bantu, as well as the Bushman. In the Americas to the Hopi of the Southwest and to the Xingu of the Amazon.

The Dionysian mysteries have not been practiced in millennia, and the bullroarer has been stripped of any mystic meaning in Europe, where it is now a child’s plaything—the original fidget spinner, complete with a bloody backstory. The only two exceptions in Europe prove the rule. Take a moment to try and guess them based on what has been presented so far.

Answer: they are those with the best claims of being indigenous, the Basque and the Sami. The Basque are an interesting case of syncretism, where their pagan bullroarer rites of spring have been rolled into the Easter celebration3. For the Sami, it is part of their shamanic practices. It is popular to suggest that both cultures preserve pre-Indo-European culture. The Basque, from Ice Age Europe, and the Sami, from Siberia, also back to the Ice Age if one accepts continuity between Siberian shamanism now and in the Paleolithic4. The bullroarer is part of Siberian folk music (1,2) and has been found in Europe going back 20,000-30,000 years. It is interesting that the two most conservative cultures in Europe either both retained or independently invented the bullroarer tradition.

These exceptions aside, Europe has secularized the bullroarer. Such a process seems to have happened in many parts of the world. Otto Zerries mentions “An interesting case occurs among the Apinayé [an Amazonian tribe], who consider the bullroarer simply as a toy; nevertheless they call it "me-galo", which means soul, ghost, shadow.” Similarly, the bullroarer is a toy to the Kikuya, a Bantu tribe in Kenya, whereas it is of utmost ceremonial import to the rest of their Bantu neighbors. So, the bullroarer question is two-fold:

Why is the bullroarer used similarly in mystery cults worldwide?

Why is it part of primitive religion and then fades?

Almost no one argues that there is nothing to explain, that the similarities are trivial. The answer to 1) has always been diffusion or the psychic unity of mankind. The latter posits the human mind is so similar that it unerringly finds the same solution to the same problems, and bullroarer cults are largely independent developments. The problems the bullroarer purportedly solves are related to who we are and where we came from, and how to answer that in a way that promotes social cohesion (the establishment of a mystery cult). This has a nice universalist ring to it until one considers 2, that cultures seem to “progress” out of the bullroarer phase. Indeed, early researchers who rejected diffusion suggested a psychic unity of the savage mind rather than of all minds. Europeans had put such barbarous worship behind them, and it was only a memory by the time of antiquity.

Further, it should be noted that psychic unity is never used on a regional level. For example, bullroarer cults are universal across Australia, spanning the two dozen or so language families. These cults share cognates and songlines and tell similar stories of how the world began. The age of this religious tradition is debated (the Rainbow Serpent is about 6,000 years old), but it is never treated as evidence of the psychic unity of the Aboriginal mind. Australians don’t have the bullroarer gene (or the Rainbow Serpent gene). It’s obvious there was a common root at some point in the past. In fact, one can do this in each region, as the bullroarer cults of Papua New Guinea or the Amazon or the Americas also exhibit local variations that suggest a phylogeny, and where it’s already accepted that there is region-wide cultural diffusion, such as Clovis culture in the Americas, agriculture in PNG and the dingo in Australia. Consider the bullroarer phylogeny in just Australia and Papua New Guinea, which were one landmass until about 8,000 years ago. If one posits separate phylogenies, then they ought to be younger than 8,000 years. And if that’s the case, why did both regions invent strikingly similar bullroarer cults in the last 8,000 years, which then spread internally? This is a strict “Ages of Man” model where every culture passes through the bullroarer stage, invariably connecting the instrument to mystery cults, death and rebirth, and myths of a primordial matriarchy.

Modern anthropologists are allergic to linking the phylogenetic tree between any two continents. For example, one possible path for the bullroarer cult is from Eurasia to Papua New Guinea at the end of the Ice Age and then from there on to Australia. There are many suggested cultural phylogenies that old: Afroasiatic, pronouns in Euroasiatic, the Cosmic Hunt, serpent sacrifice, and Australian firestick rituals. Deep time isn’t an issue. But culture spreading between continents is deemed problematic. Consider the treatment of diffusion in “A History of Anthropological Theory,” a widely used textbook:

“Related to psychic unity was the doctrine of independent invention, an expression of faith that all peoples could be culturally creative. According to this doctrine, different peoples, given the same opportunity, could devise the same idea or artifact independently, without external stimulus or contact. Independent invention was one explanation of cultural change. The contrasting explanation was diffusionism, the doctrine that inventions arise only once and can be acquired by other groups only through borrowing or immigration. Diffusionism can be construed as non-egalitarian because it presupposes that some peoples are culturally creative while others can only copy.”

Let it be said that diffusion does not presuppose a single invention or racial superiority. All that needs to hold is that it’s easier to share an idea than to invent it, and you get significant diffusion. This could be regional or even worldwide if the data support it. The canonical example is writing, which was invented independently around five times5. As it stands, Chinese and Korean characters share a common ancestor. If there was evidence the same held for Chinese and Sumerian, this would not be racist. It’s just that the data don’t support it.

For a century, the bullroarer debate was on whether mystery cults were reading from the same religious “script.” Then, the anti-diffusionists won the day, and the bullroarer was forgotten. After describing two extreme schools of diffusionist thought, the textbook goes on:

“An undercurrent of both approaches was the hereditarian belief that some human races were more capable of cultural innovation than others. Hereditarianism, or “racism,” was an attitude that early-twentieth-century anthropologists strongly opposed. For this reason, doctrinaire diffusionism never achieved a wide following. In the wake of the racial policies of National Socialism (i.e., Nazism), it became disreputable and faded from mainstream theoretical view. Accordingly, in recent decades, anthropologists, including archaeologists, who propose early human contact over long distances have been held accountable with the burden of proof.”

Being “held accountable with the burden of proof” is a euphemism for isolated demands for rigor6. In fact, not giving bullroarer diffusion a fair shake is explicitly stated by some (non-diffusionist) anthropologists:

“Interest has long since waned in ‘diffusionist’ anthropology, but recent evidence is very much in accord with its predictions. Today we know that the bullroarer is a very ancient object, specimens from France (13,000 B.C.) and the Ukraine (17,000 B.C.) dating back well into the Paleolithic period. Moreover, some archeologists—notably, Gordon Willey (1971)—now admit the bullroarer to the kit-bag of artifacts brought by the very earliest migrants to the Americas. Nevertheless, modern anthropology has all but ignored the broad historical implication of the wide distribution and ancient lineage of the bullroarer.” ~Thomas Gregor, Anxious Pleasures, 1973

Or Bethe Hagen in 2009:

“The bullroarer and buzzer were once well-known and well-loved by anthropologists. They functioned within the profession as hallmark artifacts that symbolized the cultural relativist commitment to independent invention even as evidence (size, shape, meaning, uses, symbols, ritual) stretching tens of thousands of years across human history pointed to diffusion.” ~Bethe Hagen, Spin as Creative Consciousness, 2009

Considering all this, the simplest explanation is as follows:

In the Upper Paleolithic, new ideas about how one should relate to the spiritual and social world were ritualized in mystery cults that happened to use the bullroarer. These spread from Eurasia to the rest of the world, perhaps around the end of the Ice Age. This outline used to be a common view among anthropologists, but eventually, the bullroarer was forgotten because the straightforward explanation runs afoul of cherished biases in the field7. For example, Australian Dreamtime stories tell of a time when mysterious civilizing figures showed up on canoes and established a mystery cult8. Demonstrating a kernel of truth to this Aboriginal myth is not a good career move for an anthropologist. As such, the bullroarer is now largely ignored. I hope this article helps to change that. Understand the bullroarer, and we understand our past.

Outline:

Each date is hyperlinked to the item’s location in the document. The most important entries are bolded.

1885: Custom and Myth, Andrew Lang

1890: Golden Bough, James Frazer

1892: The Medicine Men of the Apache, John G. Bourke

1898: Bullroarers Used by the Australian Aborigines, RH Matthews

1898: The Study of Man, Alfred C. Haddon

1899: The Native Tribes of North Central Australia, Baldwin Spencer and F. J. Gillen

1909: The Threshold of Religion, RR Marett

1912: The Lost Language Of Symbolism Vol I, Harold Bayley

1913: Two Years with the Natives in the Western Pacific, Felix Speiser

1919: Balder the Beautiful Vol-ii, James George Frazer

1920: Primitive Society, Robert H. Lowie

1922: Bantu Beliefs and Magic with Particular Reference to the Kikuyu and Kamba Tribes of Kenya Colony, C.W. Hobley

1929: Tribal Initiations and Secret Societies, EM Loeb

1929: Secret Societies and the Bull-roarer, Nature editorial board

1932: The Patwin and Their Neighbors, A.L. Kroeber

1937: Excavations at Snaketown, Vol 2: Comparisons and Theories, Harold S. Gladwin

1942: Das Schwirrholz: Investigation on the Distribution and Significance of Bullroarers in Cultures, Otto Zerries

1950: Early Man in the New World, Kenneth Macgowan and Joseph A. Hester, Jr

1952: Old World Overtones in The New World: Some Parallels with North American Indian Musical Instruments, Theodore A. Seder

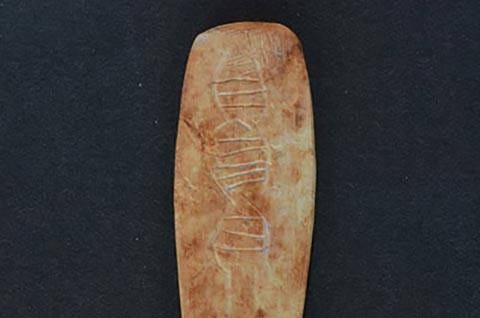

1954: A Magdalenian ‘Churinga,’ Henry Field

1959: The Masks of God: Primitive Mythology, Joseph Campbell

1960: The Origin of the Kemanak, Jaap Kunst

1966: The Slain God. Worldview of an Early Culture, Adolf Ellegard Jensen

1967: The Distribution of Sound Instruments in the Prehistoric Southwestern United States, Donald Brown

1970: Man and the Invisible, Jean Servier

1973: The Bullroarer in History and in Antiquity, JR Harding

1973: Anxious Pleasures: The Sexual Lives of an Amazonian People, Thomas Gregor

1978: A Psychoanalytic Study of the Bullroarer, Alan Dundes

1988: Myths of Matriarchy Reconsidered, Deborah B. Gewertz

1992: Ritual Masks: Deceptions and Revelations, Pernet Henry

1995: Blood Relations: Menstruation and the Origins of Culture, Chris Knight

1998: What is wrong with music archaeology? A critical essay from Scandinavian perspective including a report about a new find of a bullroarer, Cajsa Lund

2001: Gender in Amazonia and Melanesia: An Exploration of the Comparative Method, Gregor and Tuzin

2003: The Evolutionary Origins and Archaeology of Music, Iain Morley

2009: Spin as Creative Consciousness, Bethe Hagen

2010: The Bullroarer Cult in Cuba, Michael Marcuzzi

2011: The Neolithic in Turkey, New Excavations & New Research, Vecihi Özkaya, Aytaç Coşkun

2013: The prehistory of music: human evolution, archaeology, and the origins of musicality, Iain Morley

2015: The Domesticated Penis: How Womanhood Has Shaped Manhood, Loretta Cormier and Sharyn Jones

2016: A Decorated Bone 'Spatula' from Göbekli Tepe. On the Pitfalls of Iconographic Interpretations of Early Neolithic Art, Dietrich and Notroff

2016: The Waters of mendangumeli: A masculine psychoanalytic interpretation of a new guinea Flood myth— and Women’s laughter, Eric Silverman

2017: Cosmology Performed, the World Transformed: Mimesis and the Logical Operations of Nature and Culture in Myth in Amazonia and Beyond, Deon Liebenberg

2019: A functional investigation of southern Cape Later Stone Age artefacts resembling aerophones, Kumbani et al

2022: Australian Aboriginal symbols found on mysterious 12,000-year-old pillar in Turkey—a connection that could shake up history, Archeology World team

A chronology of bullroarer research:

1885: Custom and Myth, Andrew Lang

After an introductory chapter on the methods of comparative mythology, Lang turns to his subject proper with a chapter, “The Bull-Roarer: A Study of the Mysteries”9 in which he intends “to show that certain peculiarities in the Greek mysteries occur also in the mysteries of savages and that on Greek soil they are survivals of savagery.”

“The bull-roarer has, of all toys, the widest diffusion, and the most extraordinary history. To study the bull-roarer is to take a lesson in folklore. The instrument is found among the most widely severed peoples, savage and civilised, and is used in the celebration of savage and civilised mysteries. There are students who would found on this a hypothesis that the various races that use the bull-roarer all descend from the same stock. But the bull roarer is introduced here for the very purpose of showing that similar minds, working with simple means towards similar ends, might evolve the bull-roarer and its mystic uses anywhere. There is no need for a hypothesis of common origin, or of borrowing, to account for this widely diffused sacred object.”

Bullroarers are selected because they lay bare the two schools of thought at the time: cultural evolution and diffusion. Cultural evolution holds that there are natural stages of culture: savagery, barbarism, and civilization. Savage minds everywhere are alike, and therefore, we should expect them to produce similar cultural artifacts from sustenance to religion. Even down to the type of instrument that symbolizes the voice of god and the custom that women should be killed, blinded, or gang raped if they ever see the instrument. The alternative is that such practices were invented (possibly only once), are particular to a place and time, and spread due to the vicissitudes of (pre-)history. There may be psycho-social “hooks” that keep a practice in place. But the attractor state is not so strong that the practices are called from the ether whenever non-literate groups of people start experimenting with religion.

Lang shows how mystery cults in the Americas, Africa, Oceania, Australia, and Ancient Greece all use (or have used) bullroarers in their most important rites. Often, women are barred, initiates are tortured and painted, and the mysteries are connected to the tradition of a great deluge. Because cultural evolution does not suppose a psychic unity of all minds but rather a psychic unity of all savages, Lang must explain why the bullroarer is religiously central during the first stage of cultural development and then later discarded when civilization is achieved.

To do this, Lang takes for granted that mystery cults will exist, that they will need some sort of church bell to call people to the assembly, that the bullroarer is the simplest solution to this problem, and if it’s a boy’s club, that it could naturally develop for women to be put to death if they hear the sound.

“There are thus undeniably close resemblances between the Greek mysteries and those of the lowest contemporary races. As to the bull-roarer, its recurrence among Greeks, Zunis, Kamilaroi, Maoris, and South African races, would be regarded, by some students, as a proof that all these tribes had a common origin, or had borrowed the instrument from each other. But this theory is quite unnecessary. The bull-roarer is a very simple invention. Anyone might find out that a bit of sharpened wood, tied to a string, makes, when whirred, a roaring noise. Supposing that discovery made, it is soon turned to practical use. All tribes have their mysteries. All want a signal to summon the right persons together and warn the wrong persons to keep out of the way. The church bell does as much for us, so did the shaken seistron for the Egyptians. People with neither bells nor seistra find the bull-roarer, with its mysterious sound, serve their turn. The hiding of the instrument from women is natural enough. It merely makes the alarm and absence of the curious sex doubly sure…”

“The conclusion from all these facts seems obvious. The bull-roarer is an instrument easily invented by savages, and easily adopted into the ritual of savage mysteries. If we find the bull-roarer used in the mysteries of the most civilised of ancient peoples, the most probable explanation is, that the Greeks retained both the mysteries, the bull-roarer, the habit of bedaubing the initiate, the torturing of boys, the sacred obscenities, the antics with serpents, the dances, and the like, from the time when their ancestors were in the savage condition.”

This explanation is tenuous, but Lang’s framing of the problem and gathering of the facts is valuable. From the very beginning, the bullroarer was connected to male mystery cults involving serpents, death, and rebirth.

1890: Golden Bough, James Frazer

A few years later, James Frazer published The Golden Bough, one of the most influential anthropology books of all time. Bullroarers were no more than a side note, but their associations are informative:

“Examples of this supposed death and resurrection at initiation are the following. Among some of the Australian tribes of New South Wales, when lads are initiated, it is thought that a being called Thuremlin takes each lad to a distance, kills him, and sometimes cuts him up, after which he restores him to life and knocks out a tooth. In one part of Queensland the humming sound of the Bullroarer, which is swung at the initiatory rites, is said to be the noise made by the wizards in swallowing the boys and bringing them up again as young men. ‘The Ualaroi of the Upper Darling River say that the boy meets a ghost which kills him and brings him to life again as a man.’”

According to Cormier and Jones (2015), “Frazer describes the use of the bullroarer in harvest rituals by so-called savage people of New Guinea as being of the same nature as ecstatic cult rituals of the Dionysian Mysteries.”

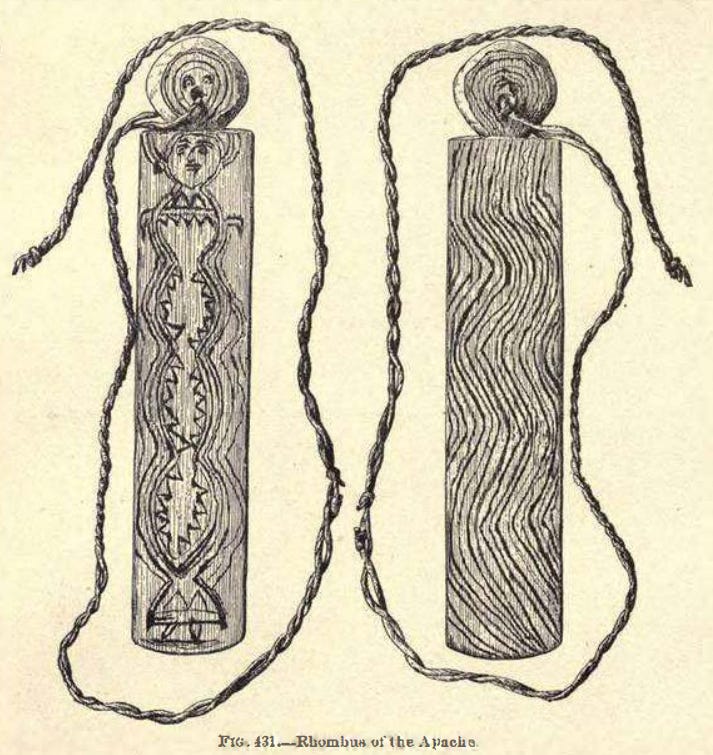

1892: The Medicine-Men of the Apache, John G. Bourke

Bullroarer use is discussed among the Apache, Navajo, Hopi (Tusayan), Zuni, Rio Grande Pueblo tribes, and Utes.

“The identification of the rhombus or “bull roarer” of the ancient Greeks with that used by the Tusayan in their snake dance was first made by E. B. Tylor in the Saturday Review in a criticism upon “The Snake Dance of the Moquis of Arizona.””10

Notably, the snake dance involves being bitten by rattlesnakes, another surprising similarity with the Greek mysteries, which some classicists also think involved snake venom.

1898: Bullroarers Used by the Australian Aborigines, RH Matthews

Matthews quotes authors from all over the continent going back to the 1840s to demonstrate that the bullroarer is universally used in initiation ceremonies in Australia. Like many others, he notes, “The uninitiated or the women are not permitted to see it or to use it under pain of death.” Unlike most, he reports that the strings of the bullroarer were often constructed with human hair.

It’s important to remember that many of these scholars were not in communication or even friendly towards one another. Therefore, it doesn’t seem likely that the bullroarer is a fake class of ritual object imposed by anthropologists; many independent observations found it to be central to mystery cults the world over.

1898, The Study of Man, Alfred C. Haddon

FIG. 40. Comparative Series of Bull-Roarers:

Bushman (after Ratzel);

Eskimo (after Murdoch), 7½×2;

Apache, North America (after Bourke), 8×1½;

Pima, North America (after Schmeltz), 15½×1;

Nahuaqué, Brazil (after V. d. Steinen), 13×2;

Bororo, Brazil (after V. d. Steinen), 15×3½;

Patani Malay, E. coast of Malay Peninsula (original, from a description by W. Skeat), 8;

Sumatra (after Schmeltz), 4½×1;

New Zealand (original), 13½×4½

Toaripi, British New Guinea (original), 20×3½, 11½×1;

Mabuiag, Torres Straits, 16×3;

Muralug, Torres Straits (original), 6½×1½;

Mer, Torres Straits (original), 5½×1½;

South Australia (after Etheridge), 14½×3; both sides of the same specimen are shown;

Wiradhuri tribes, N. S. W. (after Matthews), 13½×2¼;

Clarence River tribe, N. S. W. (after Matthews), 5×1;

S. E. coast, N. S. W. (after Matthews, 13×4½;

Kamilaroi tribe, Weir River, Queensland (after Matthews), 11×1½.

Matthews was writing under the impression there was no systematic study of the bullroarer in Australia. Little did he know Haddon was working on a worldwide study that same year. In his project to understand the nature of man, Haddon devoted a chapter to “the most ancient, widely spread, and sacred religious symbol in the world.” He draws from Lang and adds some examples of his own, including the figure above. Like Lang, he prefers independent invention. The artifact could have been produced by “similar minds, working with simple means towards similar ends.” If it did diffuse, it was so long ago there are no tools to investigate (this is before carbon dating, genetics, etc):

“The distribution of the bull-roarer seems to preclude the view that it has had a single origin and been carried by conquest, trade, or migration, in the usual way. It is impossible to say whether it formed part of the religious equipment of man in his first wanderings over the earth. The former view does not appear to be at all probable: it is impossible to prove the latter supposition.

The implement itself is so simple that there is no reason why it should not have been independently invented in many places and at diverse times. On the other hand, it is usually regarded as very sacred, and as being either a god itself, as representing a god, or as having been taught to men by a god. Where this is the case there is every reason to believe that its use is very ancient. So that it is probable that in certain areas it was early discovered and has since been transmitted to the descendants, and perhaps to the neighbours, of the original inventors.”

The table is informative to the type of categories that were part of the initial study of the bullroarer. Over the next century, dozens of other cultures will be added to similar frameworks:

Interestingly, he reports that in Ireland, there may have been memories of when it was more than a toy:

“Those given to me were made for me, and may not represent the common form of bull-roarer in the north-east corner of Ireland. My informant stated that once when, as a boy, he was playing with a ‘boomer’ an old country woman said it was a ‘sacred’ thing.”

“I have been told that the bull-roarer was known as a ‘thunder-spell’ in some parts of Scotland, and in Aberdeen as a ‘thunder-bolt.’ Professor Tylor also records it from Scotland. My friend, Mrs. Gomme, has very kindly allowed me to copy the following from the second volume of her Traditional Games of England, Scotland, and Ireland (1898, p. 291):

** Thun'er- Spell, — A thin lath of wood, about six inches long and three or four inches broad, is taken and rounded at one end…

1899 The Native Tribes of North Central Australia, by Baldwin Spencer and F. J. Gillen

This general work on Australian culture includes a chapter on the bullroarer:

“Amongst the aborigines of the Centre, as indeed everywhere else where they are found, considerable mystery is attached to their use—a mystery which has probably had a large part of its origin in the desire of the men to impress the women of the tribe with an idea of the supremacy and superior power of the male sex.”

The Arunta hold that when a child’s soul enters his mother’s womb, his spirit tree (nanja) is said to drop a bullroarer (churinga). When the child is born, the mother will describe where she thinks the tree is, and her male relatives will go look for the bullroarer. If they don’t find it, they will make one using whatever wood they find nearby. The authors assume the ritual is something like Santa Claus, where the men, typically the grandfather, hides the bullroarer before the occasion.

Other informative quotes:

“We have evidently in the Churinga [bull-roarer] belief a modification of the idea which finds expression in the folklore of so many peoples, and according to which primitive man, regarding his soul as a concrete object, imagines that he can place it in some secure spot apart, if needs be, from his body, and thus, if the latter be in any way destroyed, the spirit part of him still persists unharmed.”

“[The Arunta] associate with the bull-roarer the idea of the spirit part of some great ancestor.”

“[Among the Kurnai] the bull-roarer is identified with a man who…conducted the first ceremony of initiation, and he made the bull-roarer which bears his name.”

“To return however to the Arunta. We meet in tradition with unmistakable traces of the idea that the Churinga is the dwelling place of the spirit of the Alcheringa [Dreamtime] ancestors. In one special group of Achilpa men, for example, the latter are reported to have carried about a sacred pole or Nurtunja with them during their wanderings. When they came to a camping place and went out hunting the Nurtunjawas erected, and upon this the men used to hang their Churinga when they went out from camp, and upon their return they took them down again and carried them about. In these Churinga they kept, so says the tradition, their spirit part.”

1909: The Threshold of Religion, RR Marett

In the early 20th century, many thought that the first religious notions were animist, attributing spiritual essence to natural objects, places, and phenomena. Lightning became a god, and mammoths had spirits. Marett proposed a competing model: the first religious feeling was awe. This, he argued, was a more diffuse transcendence separate from, say, the agency of a spirit. Like others, he includes a chapter on the bullroarer, where he argues that all supreme gods in Australia started out as bullroarers, and then their character took form to explain the awe of the ceremonies where they were used. His explanation veers toward word salad11, but, interestingly, he was led down this path by learning that the name for bullroarer is the same as the high god in some tribes12. Importantly, the bullroarer has been used in theories on the genesis of religion for over 100 years. This is striking, given early examples are found in ritual sites like Gobekli Tepe, which are still theorized to be the birth of religion.

1912: The Lost Language Of Symbolism Vol I, Harold Bayley

“Among the European mystics of the Middle Ages the bullroarer was apparently considered to be an emblem of the regenerating power of the Holy Spirit.”

1913: Two Years with the Natives in the Western Pacific, Felix Speiser

Some accounts have not aged well:

“In general, the Ambrymese are more agreeable than the Santo people. They seem more manly, less servile, more faithful and reliable, more capable of open enmity, more clever and industrious, and not so sleepy.

Assisted by my excellent guide, I set about collecting, which was not always a simple matter. I was very anxious to procure a “bull-roarer,” and made my man ask for one, to the intense surprise of the others; how could I have known of the existence of these secret and sacred utensils? The men called me aside, and begged me never to speak of this to the women, as these objects are used, like many others, to frighten away the women and the uninitiated from the assemblies of the secret societies. The noise they make is supposed to be the voice of a mighty and dangerous demon, who attends these assemblies.

They whispered to me that the instruments were in the men’s house, and I entered it, amid cries of dismay, for I had intruded into their holy of holies, and was now standing in the midst of all the secret treasures which form the essential part of their whole cult. However, there I was, and very glad of my intrusion, for I found myself in a regular museum. In the smoky beams of the roof there hung half-finished masks, all of the same pattern, to be used at a festival in the near future; there was a set of old masks, some with nothing left but the wooden faces, while the grass and feather ornaments were gone; old idols; a face on a triangular frame, which was held particularly sacred; two perfectly marvellous masks with long noses with thorns, carefully covered with spider-web cloth. This textile is a speciality of Ambrym, and serves especially for the preparation and wrapping of masks and amulets. Its manufacture is simple: a man walks through the woods with a split bamboo, and catches all the innumerable spider-webs hanging on the trees. As the spider-web is sticky, the threads cling together, and after a while a thick fabric is formed, in the shape of a conical tube, which is very solid and defies mould and rot. At the back of the house, there stood five hollow trunks, with bamboos leading into them. Through these, the men howl into the trunk, which reverberates and produces a most infernal noise, well calculated to frighten others besides women. For the same purpose cocoa-nut shells were used, which were half filled with water, and into which a man gurgled through a bamboo. All this was before my greedy eyes, but I could obtain only a very few articles. Among them was a bull-roarer, which a man sold me for a large sum, trembling violently with fear, and beseeching me not to show it to anybody. He wrapped it up so carefully, that the small object made an immense parcel. Some of the masks are now used for fun; the men put them on and run through the forest, and have the right to whip anybody they meet. This, however, is a remnant of a very serious matter, as formerly the secret societies used these masks to terrorize all the country round, especially people who were hostile to the society, or who were rich or friendless.

These societies are still of great importance on New Guinea, but here they have evidently degenerated. It is not improbable that the Suque has developed from one of these organizations. Their decay is another symptom of the decline of the entire culture of the natives; and other facts seem to point to the probability that this decadence may have set in even before the beginning of colonization by the whites.

My visit to the men’s house ended, and seeing no prospects of acquiring any more curiosities, I went to the dancing-ground, where most of the men were assembled at a death-feast, it being the hundredth day after the funeral of one of their friends. In the centre of the square, near the drums, stood the chief, violently gesticulating. The crowd did not seem pleased at my coming, and criticized me in undertones. A terrible smell of decomposed meat filled the air; evidently they had all partaken of a half-rotten pig, and the odour did not seem to trouble them at all.

1919: Balder the Beautiful Vol-ii, James George Frazer

Frazer spends the better part of a chapter seeking to explain why male puberty rites worldwide feature death and resurrection. The bullroarer is mentioned dozens of times. This case in New Guinea is interesting because, in Australia (where the bullroarer may have later spread), the Djungawal sisters are said to obtain the initiation rituals while in the belly of the rainbow serpent. Perhaps death in the belly of the beast is an ancient element of the bullroarer rites.

For this purpose a hut about a hundred feet long is erected either in the village or in a lonely part of the forest. It is modeled in the shape of the mythical monster; at the end which represents his head it is high, and it tapers away at the other end. A betel palm, grubbed up with the roots, stands for the backbone of the great being and its clustering fibres for his hair; and to complete the resemblance the butt end of the building is adorned by a native artist with a pair of goggle eyes and a gaping mouth. When after a tearful parting from their mothers and women folk, who believe or pretend to believe in the monster that swallows their dear ones, the awe-struck novices are brought face to face with this imposing structure, the huge creature emits a sullen growl, which is in fact no other than the humming note of bullroarers swung by men concealed in the monster’s belly.

…

It is highly significant that all these tribes of New Guinea apply the same word to the bull-roarer and to the monster, who is supposed to swallow the novices at circumcision, and whose fearful roar is represented by the hum ot the harmless wooden instruments. The word in the speech of the Yabim and Bukaua is balum ; in that of the Kai it is ngosa; and in that of the Tami it is kani. Further, it deserves to be noted that in three languages out of the four the same word which is applied to the bull-roarer and to the monster means also a ghost or spirit of the dead, while in the fourth language (the Kai) it signifies “ grandfather.” From this it seems to follow that the being who swallows and disgorges the novices at initiation is believed to be a powerful ghost or ancestral spirit, and that the bull-roarer, which bears his name, is his material representative.

1920: Primitive Society, Robert H. Lowie

Lowie was instrumental in developing modern anthropology, twice serving as editor of the American Anthropologist. In his classic on Primitive Society, he argues:

“These resemblances are hardly of a character to be ignored. They aroused the interest of Andrew Lang, who explained them as the result of “similar minds, working with simple means towards similar ends” and expressly repudiated the “need for a hypothesis of common origin, or of borrowing, to account for this widely diffused sacred object.” In this interpretation he has been followed by Professor von der Steinen, who remarks that so simple a contrivance as a board attached to a string can hardly be regarded as so severe a tax on human ingenuity as to require the hypothesis of a single invention throughout the history of civilization. But this is to mistake the problem. The question is not whether the bull-roarer has been invented once or a dozen times, nor even whether this simple toy has once or frequently entered ceremonial associations. I have myself seen priests of the Hopi Flute fraternity whirl bullroarers on extremely solemn occasions, but the thought of a connection with Australian or African mysteries never obtruded itself because there was no suggestion that women must be excluded from the range of the instrument. There lies the crux of the matter. Why do Brazilians and Central Australians deem it death for a woman to see the bullroarer? Why this punctilious insistence on keeping her in the dark on this subject in West and East Africa and Oceania? I know of no psychological principle that would urge the Ekoi and the Bororo mind to bar women from knowledge about bull-roarers and until such a principle is brought to light I do not hesitate to accept diffusion from a common center as the more probable assumption. This would involve historical connection between the rituals of initiation into the male tribal societies of Australia, New Guinea, Melanesia, and Africa and would still further confirm the conclusion that sex dichotomy is not a universal phenomenon springing spontaneously from the demands of human nature but an ethnographical feature originating in a single center and thence transmitted to other regions.”

Later research showed Amazonian tribes also barred women from viewing the bullroarer. So, add South America to his list.

1922: Bantu Beliefs and Magic with Particular Reference to the Kikuyu and Kamba Tribes of Kenya Colony, C.W. Hobley

“Inquiries were made as to whether the bull-roarer, which is well known in Kikuyu as kiburuti, was used in these [initiation] ceremonies, but curiously enough it appears to survive only as a child’s toy, whereas in many of the neighbouring tribes it and its first cousin, the friction drum, are regularly used in initiation ceremonial.”

1929: Tribal Initiations and Secret Societies, EM Loeb

“The case for diffusion is even stronger than stated by Lowie. Not only is the bull-roarer tabooed to women when used in connection with male initiation rites, but it is also almost invariably represented as the voice of spirits. Nor does the bull-roarer travel alone in connection with male initiation rites. This paper has demonstrated the fact that a form of tribal marking, a death and resurrection ceremony, and an impersonation of ghosts or spirits is found among male tribal initiation rites as the usual concomitants of the bull-roarer. There is no psychological principle involved which would necessarily group these elements together, and they therefore must be regarded as having been fortuitously grouped in one locality of the world, and then disseminated as a complex.”

This complex, Loeb argued, includes: “(1) the use of the bullroarer, (2) the impersonation of ghosts, (3) the "death and resurrection" initiation, and (4) the mutilation by cutting.”

As a specialist in Native American culture, he adds dozens of new examples to the literature. A subsequent paper compares initiations in North and South America, comparing 60 cultures from Alaska to Tierra del Fuego. Of interest to EToC, he notes: “Bachofen, Lippert, Briffault, and P. Schmidt have connected secret societies with the matriarchate [the end of the primordial matriarchy]. They believe that secret societies arose when men organized to put an end to woman-rule.” Bachofen published Mother Right in 1861 and died in 1887 before much of the anthropology outside of Europe had begun. He based his ideas on classical literature. The application of his ideas to mystery cults in Australia or the Amazon should be treated as an out-of-sample prediction.

1929: Secret Societies and the Bull-roarer, Nature editorial board

The most storied science journal lends its support to Loeb’s interpretation:

“From the distribution it is inferred that these traits are of archaic, possibly palaeolithic, origin, and not a matter of recent diffusion. As regards the bull-roarer, earlier theories are to be regarded as untenable. It would be possible to regard it as of independent origin in different regions only if attention were confined to its use as a toy or for purposes of magic. In connexion with initiation and secret societies, it is always associated with a form of tribal marking, a death and resurrection ceremony, and an impersonation of ghosts and spirits. It is tabooed to women and is invariably represented as the voice of spirits; but when found outside the area of initiation rites and secret societies it is neither. As there is no psychological principle which debars women from the sight of the instrument in Oceania, Africa, and the New World, it cannot be regarded as due to an independent origin and it must be inferred that it has been diffused from a common centre.”

1932: The Patwin and Their Neighbors, A.L. Kroeber

A colleague at Berkeley says Loeb’s worldwide distribution are the only way to understand specific instances of the bullroarer cult. Many anthropologists accepted Loeb’s ideas; this wasn’t fringe.

“A historical reconstruction of the course of development of the Kuksu system cults cannot as yet be carried very far on the basis of the data themselves. A general scheme of interpretation on a continental or world-wide basis might conceivably take one further. If for instance like Loeb one starts from the position that tribal initiations everywhere are due to a single, ancient diffusion with features like bullroarer, mutilation, death and resurrection rites, spirit impersonations as original criteria, and that secret societies grew out of this substratum as secondary parallels, considerable headway can be made toward reconstructing the history of the California or any other system.”

1937: Excavations at Snaketown, Vol 2: Comparisons and Theories, Harold S. Gladwin

It’s an oddity that reaction to the search for Atlantis has muddied the bullroarer debate for a full century:

“Passing on from physical type to culture, it can be said that the Texas industries described above, fall almost entirely within the boundaries of the Southern long-heads, Map 7. Nordenskjöld, Dixon, and others have enumerated a long list of traits which have been found in South America, which are also known to occur in Australia and Melanesia. Some of these traits, such as the spear-thrower, darts with fore-shafts, curved throwing-sticks, bull-roarers, and various forms of self-mutilation, as tattooing, and finger-amputation, have also been discovered in southern North America. A great deal of ingenuity has been used in providing explanations for the way in which these and other traits were acquired and, in almost every instance, the possibility has been denied that diffusion from Asia to America could have been the cause.

The reasons for this unwillingness to accept a rather logical explanation are twofold. First, such acceptance might seem to lend countenance to the extravagant theories which have been advanced by G. Elliot Smith in "The Ancient Egyptians and the Origins of Civilisation"; also by W. H. Perry in his "Children of the Sun: A Study in the Early History of Civilisation."

…

As a more or less direct consequence, whenever the question arises as to the independent invention or the diffusion of any given trait, immediately, at the first sound of the alarm, comes the solid body of American archaeologists to uphold the sanctity of American native inventiveness. In spite of the uniformity of opinion on this subject, I fell like murmuring, with the Queen in Hamlet, “The lady doth protest too much, methinks.”

Admitting freely that trans-Pacific or trans-Antarctic contact is not to be considered as more than a remote possibility, and again admitting that the spread of the Heliolithic Cult belongs to the same category as the lost continents of Mu and Atlantis, is it not to be considered as a possibility that, when the Southern long-heads entered the New World via the narrow Bering Strait or the Bering Isthmus, they should also have brought with them certain material and social traits? And would this not account rather more logically than some other explanations for the long list of analogies which are known to have been shared by these people in America and those in Australia and Melanesia, particularly when vestiges of the same traits and peoples are to be found along the coasts of eastern Asia and western North and South America?”

1942: Das Schwirrholz: Investigation on the Distribution and Significance of Bullroarers in Cultures, Otto Zerries

Zerries published a book on bullroarers in Germany in 1942. For obvious reasons, this did not obtain wide circulation. In 1953 he wrote a shorter volume focusing on the instrument in South America (including discussion of its use by 40 different cultures), in part because only a few copies of his book survived the war. Zerries maintained that the wide range of the bullroarer was evidence of an ancient common culture based on the separation of the sexes. The bullroarer, according to Zerries, has “its roots in an early cultural stratum of hunting and gathering tribes.”

Zerries points out that “An interesting case occurs among the Apinayé, who consider the bull-roarer simply as a toy; nevertheless they call it ‘me-galo,’ which means soul, ghost, shadow.”

As in many other places, there are associations with snakes: “The bull-roarers of the Nahuqua are fish-shaped and decorated with snake ornaments.”

1950: Early Man in the New World, Kenneth Macgowan and Joseph A. Hester, Jr

In the section on psychic unity vs diffusion in regard to Native American culture:

“This dogma is called the autochthonous origin of Indian cultures. It asserts that practically all the traits, discoveries, and inventions which Columbus, Cortes, and Pizarro found in the New World were homegrown products—importations barred. The question at issue between the friends and the opponents of this dogma is commonly expressed as Independent Invention versus Diffusion. But the phrasing is not quite accurate: it needs a little amplification. Anything invented by man is in a sense an independent invention. In the present case we are talking of an invention made in one center, the New World, independent of a similar invention in another center, the Old. We are concerned, not with independent invention, but with parallel independent invention. “Diffusion” is still more inaccurate. Normally it means the gradual transfer of some trait or technique from one people to another, often through the intervention of a third or of a third and a fourth people. In the present discussion it is more a matter of a people’s carrying the trait or the technique to a new home. The question is not merely, “Did the Indian invent pottery?” or “Did the American Australoid invent the bull-roarer?” It is rather, “Did he invent it in the New World or the Old?” or “Did he invent it in the Old World and carry it to the New?” or “Did he invent it in the New World while another fellow invented it in the Old?””

1952: Old World Overtones in The New World: Some Parallels with North American Indian Musical Instruments, Theodore A. Seder

Before population genetics, scientists sought to understand the relationship between New and Old World populations via cultural similarities, of which bullroarers were a prime piece of evidence:

The Mountain Cahuilla of California locked their children in a room with their sacred bundle if they should happen to hear the sounds of the bull-roarer; at their jimsonweed drinking ceremony they had an official who led the novitiates in dancing, whirling the ceremonial bull-roarer to keep the women and children away from the dance house at this time. The sight of the instrument was denied Pomo women and children. The Tewa of San Ildefonso used their bull-roarers out of sight, in their kivas, where women could not see them. The Wimonuntci Ute bull-roarer was also taboo to women.

…

This simple instrument was used almost everywhere in the world, although there are occasional places where it is not found, such as Finland, northeastern Asia (except the Chukchee), and the eastern part of North America (excluding the Mattaponi). However, its importance varies according to the prominence of the societies and the secret society initiations of the various native groups. Thus, in Australia, the bull-roarer warns the women and children that the sacred mysteries are being performed, for in most tribes it is death for the women to see the initiation ceremonies or even the bull-roarer itself.

…

In North America, the bull-roarer has curative properties among the shamans of the Diegueno, Mono, Navaho, 53 Tonto Apache, Yokuts, Pomo, and Papago; formerly this was also true of the Tanaina.

The jimsonweed (datura) initiation ceremony is described in greater detail here. Regarding holes in distribution, note that the Sami use the bullroarer, and they now occupy Finland. This highlights the need to continue bullroarer research. To my knowledge, this blog post is the only document that includes the Sami and Basque in the cultural survey.

Additionally, the buzzer is discussed, a similar instrument that often appears with the bullroarer (and picked up as an item of research by Bethe Hagen in the 21st century).

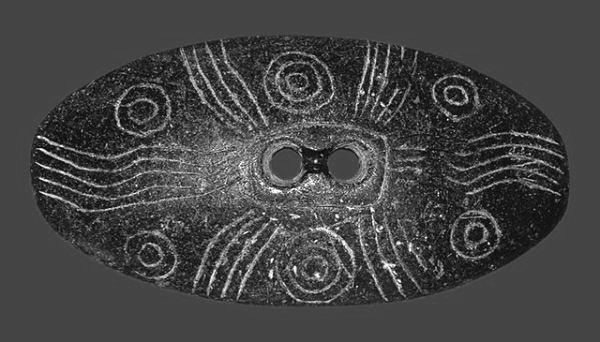

Buzz: Made of a disk, an irregular chunk of solid matter, or a blade, the buzz is fastened in most instances to a looped cord, so that it can be spun rapidly back and forth by the twining and untwining of the loop under tension from the hands. It is probably related to the bull-roarer in its origin. As proof of this we find the South American Caraja using it as a male instrument at their masked dances; the Indians of the Rocky Mountain regions use it as a charm to bring rain, snow, warm weather, favorable winds-i.e., as a fertility charm, a practice that extends to the Navaho in the Southwest, the Eyak in the Mackenzie-Yukon area, and the Naskapi in the Northeast. The buzz is used, too, by the Zuni War Priests as a warning, just as is the bull-roarer in many regions. Another point of contact between the buzz and bull-roarer may be found in its restriction to the males alone. This takes place among the Caraja of Brazil, as mentioned above. The Ingalik, who supposedly use it as a toy occasionally for boys or men, limit it to daytime use in the summer, revealing a lost symbolism.

1954: A Magdalenian ‘Churinga,’ Henry Field

At this time, the bullroarer tradition was widely believed to share a common root and insights from Australia were applied to Stone Age Europe. Here is a write-up of a discovery for “Man, A Monthly Record Of Anthropological Science”:

“The Abbé Breuil identified this ivory specimen [pictured above] as the first complete Magdalenian 'churinga' (bullroarer) ever found…The simple geometric pattern resembles that on Australian churinga and wooden shields. Since the Australian aborigines consider sacred the whirring noise of a churinga, no woman, child or uninitiated person is allowed to see a bullroarer. Thus, in Magdalenian times a similar veneration may have been observed.”

1959: The Masks of God: Primitive Mythology, Joseph Campbell

Campbell is known as a Jungian, popularizing the idea of the monomyth. But he was also a card-carrying diffusionist:

“The structure of the earlier formula is examined in the next section; we may say here only, in summary of the foregoing findings, that the Greek and Indonesian myths examined have revealed not only a shared body of ritualized motifs but also signs of a shared past, an earlier stratum of their common story, in which a snake and not a pig played the animal part. And the fact that (one way or another) the two cycles were not merely linked remotely by a long, tenuous thread, but established on a broad, common base is made evident by a baffling series of further likenesses.

For example, in both mythologies the numbers 3 and 9 were prominent. We know, also, that in the Greek rites of the goddess—and of her dead and resurrected daughter Persephone, as well as of her dead and resurrected grandson Dionysos—the choral chant, the boom of the drum, and the hum of the bull-roarer were used just as in the rites of the cannibals of Indonesia. We recognize the labyrinth theme in both traditions, associated with the underworld and rendered in the figure of a spiral: in Greece, as well as Indonesia, choral dances were performed in this pattern. The reference in the Indonesian myth to Ameta's desire to prepare a drink for himself from the blossoms of the cocopalm suggests a relationship of wine or intoxication to the cult of the maiden-plant-moon-animal complex that would correspond nicely with the formula in the archaic Mediterranean culture. And finally, is not the figure of Demeter, at the time of her departure in wrath from Olympus, bearing in each hand a long, staff-like torch, comparable to Satene standing at the labyrinthine gate, telling the people of the mythological age that she is about to leave them, and holding in each hand an arm of Hainuwele?

There can be no doubt that the two mythologies are derived from a single base. The fact was recognized some time ago by the classical scholar Carl Kerényi, and his argument has been supported since by Professor Jensen, the ethnologist chiefly responsible for the collection of the Indonesian material.”

Later, he extends the argument to Australian mysteries:

“It surely is no mere accident, nor consequence of parallel development, that has brought the bull-roarers on the scene for both the Greek and the Australian occasion, as well as the figures masquerading in white (the Australians wearing bird down, the Greek Titans seared like clowns with a white clay).”

Lang made the same connection regarding white paint used in mystery cults in Ancient Greece and modern Australia as far back as 1885. One of the great divides between the likes of Lang and Campbell vs today’s anthropologists is a willingness to work details like this into grand theories. Like the rest of science, anthropology now prioritizes epsilon improvements and tight, narrow arguments. No room for an offhand comment about how white ritual paint hints that Australians had a version of the Dionysian Mysteries.

The prospect of diffusion was not a passing interest for Campbell. Decades later, in The Historical Atlas of World Mythology: The Way of Animal Powers, Campbell wrote:

“Thus, of the two Paleolithic traditions, that of the bear cult was the older by many centuries, having originated in Neanderthal Man’s veneration of the cave bear as the Animal Master; whereas shamanism, as far as we know, developed as a tradition only in the period of the temple caves and the creative explosion of symbolic forms. Passing eastward across Siberia into America, as well as southeastwardly to Australia, shamanism traveled as but one element of a living compound that included—besides the x-ray style of animal painting and engraving, the atlatl, and the bullroarer—an elaborate complex of social regulations, ceremonials, and associated mythological ideas, which scholars have designated by the very broad term totemism.”

The Historical Atlas of World Mythology, which Campbell was working on at the time of his death, lays out a picture where the human condition—including notions of our own mortality and the existence of spirits—was discovered, and then those ideas spread. The bullroarer, among many other shared cultural features, is used as evidence for the diffusion of totemism.

1960: The Origin of the Kemanak, Jaap Kunst

“No ethnomusicologist, I think, would stand for plurigenesis as regards the bull-roarers, which even in decorative detail are often alike and are used for the same purpose wherever and whenever found (that is, where it has not become a toy for children through lapse of time or change of faith).”

In the same article, he summarizes Curt Sach’s research:

“The musicologist Curt Sachs formulated that viewpoint in the Preface to his monumental “Geist und Werden der Musikinstrumente.” He wrote:

“To those who, during many years of work, have observed time and again how the rarest cultural forms, often with totally incidental structural features at that, occur in widely scattered parts of the world and, however, in all these places the symbolic and functional aspects have been preserved, it seems almost irrelevant to emphasize and defend the kinship of these cultural forms. He has gradually formed a great picture of a world-circling cultural kinship, created over thousands of years by man himself, through migrations and sea-voyages, despite all natural obstacles.””

It’s crass, but one of the criticisms about diffusion runs something like, “You know who else thought good ideas started in one place and then spread? Nazis!” And it’s true, some documents suggest Zerries was drafted into the war. But this is quite a poor argument. Most anthropologists, including diffusionists cited here, were radical progressives for their time. Many more communists than Nazis. Sachs, for example, was a Jewish intellectual that escaped the Nazis. One of the strengths of bullroarer research is that the researchers run the ideological gamut, stretching over generations. The facts on the ground have survived the test of time, criticized from every direction.

1966: The Slain God: Worldview of an Early Culture, Adolf Ellegard Jensen

Jensen completed a PhD in physics but later became enamored with the ideas of anthropologist Leo Frobenius. He became one of the most important figures advancing Frobenius’s ideas and was appointed the leader of the Institute for Cultural Morphology following Frobenius’s death. However, this fell through as it was 1938 in Germany; he refused to divorce his Jewish wife and opposed the Nazis. After the war ended, he led the institute. He argues the bullroarer mystery cults and their attendant myths spread near the dawn of agriculture when man first ritualized death and rebirth.

“No one will readily regard the emergence of the same recognition [a link between death and procreation] among widely separated peoples as evidence of diffusion. The initiation rites, on the other hand, are cultural creations and thus have appeared at some point in the history of humanity. Imagine that Indians, Papuans, and Africans alike came to the realization of the connection between death and procreation. Can one seriously think that in Africa, New Guinea, and South America, initiation rites are created in which boys of initiation age are isolated in the bush, taught in the tribal myths and rituals, strictly kept apart from all women and girls, use a bullroarer or another noise instrument so that the boys can announce their presence at any time, invent a spirit that devours the boys and whose voice is designated by the sound of the noise instrument, and what other similarities occur in the initiation rites of Africa, Melanesia, and the Americas?

That the myths have been preserved over such long periods among non-literate peoples can be explained, on the one hand, by the fact that they are carried and retold within the framework of solemn initiation ceremonies by certain dignitaries. For example, among the Uitoto Indians, only the person who “gives the festival” and who is very knowledgeable and knows the myths of the origins of things can be the “master of the festival” (Preuß, 1923, p. 651 f.). On the other hand, the crucial factor for their preservation over such long periods lies in these cults themselves and their connection to the myth. The cults are essentially dramatic performances, whereby the myths are vividly presented to the community—especially to the growing youth.

The spread of the myth of theft in heaven, which in the version of grain theft extends to Indian tribes. Assuming that this type of myth, which extends into South America, was developed in connection with ancient Greece, seems highly unlikely. Its origin must be much further back in time.

Absolute chronology does not allow us to make assertions here, as the method based exclusively on myths cannot provide exact data. However, it does allow the assumption that the myth originated with the introduction of grain cultivation and its spread in various regions of the Earth. It is not necessary to prove how it was shown; it is enough to indicate that it returned from such remote times. It can be pointed out that the myth tells of how people were given fruits and that this theft of the originally reserved grain fruit by the heavenly people brought bread to humanity.

In general, one can say of the Prometheus myth that it only occasionally holds a relation to the myth in the cult, especially in contrast to the Hainuwele myth complex, which includes extensive cults and clearly relates to the original myth. The heavenly theft, the core theft, finds its culmination and full development in the Hainuwele myth and is rich in cultic elaboration.

…The Prometheus myth stands closer to “our” way of thinking. It is only in the imagination of the heavenly journey that it contains “mythical” elements. All other images are taken from real life.”

(Originally in German, translated by chatGPT)

In another book, Myth and Cult Among Primitive Peoples, he discusses the significance of the bullroarer to dreamtime in Australian mythology:

"One of the names current among the Ungarinyin for the mythic primal era is Lalan. … For example, our informants used to call rock paintings, rock cairns, corroborees, bull-roarers, and other things associated with the primal traditions “Lalan-nanga,” i.e., “belonging to the mythic epoch.”

The more frequently used term for the period of the mythic heroes is Ungud or, more correctly, Ungur. . . . My colleagues and I noted a third, though less frequently used designation. It was Ya-Yari, a word perhaps derivable from yari, the Ungarinyin term for dream, dream experience, visionary state, but also dream totem. In a narrower sense, the native understands by ya-yari his own vital energy, the substance of his psycho-physical existence. Ya-yari is that something within him, that makes him feel, think, and experience.” (cf, the Eve Theory of Consciousness)

1967: The Distribution of Sound Instruments in the Prehistoric Southwestern United States, Donald Brown

“Bullroarers, the only whirling aerophones in the prehistoric Southwest, are surprisingly rare. One bull roarer was found at Pecos (Kidder 1932:293), another in cliff dwellings in the Verde Valley (Bourke 1892:477), and a third in a cache at Chetro Ketl (R. Gwinn Vivian, personal communication). All were made of wood. The lack of bull roarers, like that of rasps, is somewhat puzzling, since they also play an important part in the ceremonial life of historic Southwestern groups. Bull roarers are extremely perishable and were probably few in number since they are usually a ceremonial item. This may account for the missing bull roarers.”

1970: Man and the Invisible, Jean Servier

A delightful overview with some unique citations (translated from Spanish using GPT 4.5):

Among the Dogon, the Andumbulu were the first to use the bullroarer (ibid., p. 60). The Andumbulu are the small red men who inhabited the land after the first Creation. Men dispossessed them of their Mysteries, after which they became invisible spirits.

…

Certain tribes in northern New Guinea construct a hut around thirty meters long in the form of a monster about to devour the initiates. This enormous creature produces a ferocious growl, nothing other than the roar of bullroarers spun by men hidden inside its belly" (J.G. Frazer, Balder the Beautiful, pp. 227-235, 240-243).

…

On the island of Ceylon (Sri Lanka), the bullroarer is associated with certain Buddhist ceremonies. In Sumatra, it is used in black magic to persuade spirits to seize a woman's soul and drive her mad, thus maintaining the same feared power over women as elsewhere.

In Madagascar, it is merely a child's toy, reserved, however, for boys.

…

Macalister, who devoted a long article to the bullroarer in the Encyclopaedia for Ethics and Religions, notes its presence in Scotland, Cantyre, and the County of Argyll, where it is associated with an ancient celestial deity. Tradition holds that the first bullroarer, called Srannan (pronounced Strantham), fell from the planet Jupiter. In the County of Aberdeen, cowherds still used it as recently as 1885 to protect their herds from lightning.

In the Basque Country, the bullroarer, or "furrunfara," is crafted by shepherds. It's a small wooden plank with serrated edges, decorated with various patterns including the Basque cross of swirling commas, symbolizing celestial movement. Shepherds spin the plank at the end of a cord, sometimes attached to a stick. The buzzing sound produced repels animals foreign to the herd, particularly mares that might disturb sheep at night. This use suggests an older, nocturnal purpose for the bullroarer, though not explicitly tied to initiatory rites today.

In Spain, the "brunzidor" is known in Navarre, the Basque Country, and Aragon.

In Portugal, elders forbid children from spinning their "zunas" (bullroarers) during harvest time, perhaps fearing it affects the souls of the dead departing the earth at that season.

…

The ancient Greeks knew the bullroarer, which was used in the Mysteries of Bacchus, Cotytto, and the Mother of the Gods. One author describes it, echoing the Bambara myth previously cited: "It is a small board thrown into the air to make noise" (Etym. Magn., s.v. Rombos).

Archaeologists have discovered bullroarers made of bronze, gold, or carved from fine stones. One example, preserved in the Louvre Museum, has a convex surface adorned with reliefs depicting two seated figures holding thyrsi—the symbolic staffs of initiates in the cult of Dionysus.

Finally, Pliny recounts in his Natural History (XXVIII, 5,6) that during his time in Italy, it was forbidden for women to walk along roads spinning their spindles, as it was believed this could jeopardize the success of the harvest.

Eminent ethnologists such as Loeb and Lowie have agreed that the complex involving the bullroarer and initiation rites emerged from a common center.

If, as Margaret Mead states, "most scholars agree that the civilizations of the New World developed independently from those of the Old World" (People and Places, p. 168), we still need to discover the origin of this shared certainty, how the identical symbols expressing it have traveled.

From Australia to both Americas, passing through Africa, Oceania, and Europe—from the Magdalenean man to the carpenter or stonemason Companion who vigorously spins his bullroarer—another question confronts us: that of the unity of an initiatory tradition and a primordial teaching. For this time, even in the name of “rationalism,” we cannot appeal to “luck,” “chance,” or “coincidence.”

1973: The Bullroarer in History and in Antiquity, JR Harding

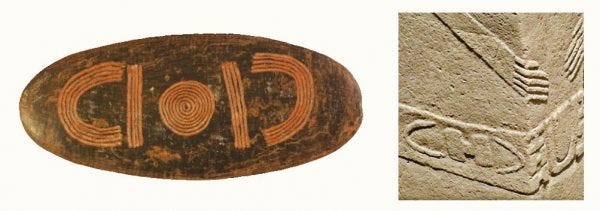

“In Europe it is possible that the bull-roarer goes back to Magdalenian times, ca. 15,000-10,000 B. C., or even to the Gravettian, ca. 25,000 -15,000 B.C. In the first case the supposition is based on the recovery of bone-, ivory- and sometimes stone-pendants, exactly imitating the blade of the instrument, from deposits of Magdalenian age in France. One from Saint Marcel, Indre, (Fig. 1) has serrated edges and an engraved design of lines and concentric circles, recalling some of the designs shown by Australian churinga.”

For some reason, this three-page paper is often cited, though it offers no new analysis. This quote highlights one recurring theme: the style of the bullroarer shows similarities across tens of thousands of years and kilometers.

1973: Anxious Pleasures: The Sexual Lives of an Amazonian People, Thomas Gregor

Gregor did fieldwork in the Amazon, one of the many people with myths of a primordial matriarchy, which ended with the theft of the bullroarers. Quoting his account at length:

“It [the patriarchal order of society] was not always so, at least not in myth. We are told that the women of ancient times (ekwimyatipalu) were matriarchs, the founders of what is now the men's house and creators of Mehinaku culture. Ketepe [whose account is in italics] is our narrator for this legend of Xingu ‘Amazons.’

THE WOMEN DISCOVER THE SONGS OF THE FLUTE. In ancient times, a long time ago, the men lived by themselves, a long way off. The women had left the men. The men had no women at all. Alas for the men, they had sex with their hands. The men were not happy at all in their village; they had no bows, no arrows, no cotton arm bands. They walked about without even belts. They had no hammocks, so they slept on the ground, like animals. They hunted fish by diving in the water and catching them with their teeth, like otters. To cook the fish, they heated them under their arms. They had nothing-no possessions at all. The women's village was very different; it was a real village. The women had built the village for their chief, Iripyulakumaneju. They made houses; they wore belts and arm bands, knee ligatures and feather headdresses, just like the men. They made kauka, the first kauka: "Tak . .. tak . .. tak," they cut it from wood. They built the house for Kauka, the first place for the spirit. Oh, they were smart, those round-headed women of ancient times. The men saw what the women were doing. They saw them playing kauka in the spirit house. "Ah, said the men, "this is not good. The women have stolen our lives!" The next day, the chief addressed the men: "The women are not good. Let's go to them." From far off, the men heard the women, singing and dancing with Kauka. The men made bullroarers outside the women's village. Oh, they would have sex with their wives very soon.

The men came close to the village, “Wait, wait,” they whispered. And then: “Now!” They leaped up at the women like wild Indians: "Hu waaaaaa!" they whooped. They swung the bullroarers until they sounded like a plane. They raced into the village and chased the women until they had caught every one, until there was not one left. The women were furious: "Stop, stop," they cried. But the men said, "No good, no good. Your leg bands are no good. Your belts and headdresses are no good. You have stolen our designs and paints." The men ripped off the belts and clothes and rubbed the women's bodies with earth and soapy leaves to wash off the designs. The men lectured the women: "You don't wear the shell yamaquimpi belt. Here, you wear a twine belt. We paint up, not you. We stand up and make speeches, not you. You don't play the sacred flutes. We do that. We are men." The women ran to hide in their houses. All of them were hidden. The men shut the doors: This door, that door, this door, that door. "You are just women," they shouted. "You make cotton. You weave hammocks. You weave them in the morning, as soon as the cock crows. Play Kauka's flutes? Not you!" Later that night, when it was dark, the men came to the women and raped them. The next morning, the men went to get fish. The women could not go into the men's house. In that men's house, in ancient times. The first one.