When Do Geneticists Believe the Human Brain Evolved?

Reflections on David Reich's recent interview and preprint

Humans are unique among animals for their capacity for symbolic thought and their reliance on complex, grammatical language. About 70,000 years ago, our species began producing art and then took over the world. During this same period, the shape of our skulls, inner ear, and vocal tract all changed. There was also selection for genes related to IQ and educational attainment. Together, this looks a lot like the evolution of our modern minds, which was the dominant interpretation of the facts among researchers until the 2000s. Then, geneticists found that there are genetic splits in the human family tree that go back 200,000 years, throwing a wrench in this model. If the human condition is genetic, when did it become established? If this was in the last 50,000 or 100,000 years, how did it leap across branches of the family tree? And, of course, what was it that gave us an edge?

This puzzle is at the heart of Dwarkesh Patel’s recent interview with geneticist David Reich. Reich points out, “Some people argue that humans are not even more intelligent than chimpanzees at some fundamental ability to compute, and that what makes humans distinctive is social learning abilities.” This prompts Patel to ask when and how our social cognition evolved.

Patel: I still don't understand. Is the answer that we just don't know what happened 60,000 years ago? Before humans and other modern humans and other types of humans were interacting, but no one was in a dominant position at least in Eurasia. Now humans not only dominate, but in fact we drove them to extinction. Do we have any idea what changed between that time?

Reich: This is really outside my expertise. There are ideas that have been floated, which I'll summarize possibly badly. In every group of human beings of hundreds of people—which is the size of a band—or sometimes a thousand people, they accumulate shared cultural knowledge about tools, life strategies, and build up shared knowledge more and more. But if you have a limited-sized group that's not interacting with a sufficiently large group of people, occasionally this group has an information loss. There's a natural disaster, key elders die, and knowledge gets lost. There's not a critical mass of shared knowledge. But once it goes above some kind of critical mass, the group can get larger. The amount of shared knowledge becomes greater. You have a runaway process where an increasing body of shared knowledge of how to make particular tools and patterns of innovation, language, conceptual ideas, run amok.

Note that this doesn’t answer when humans evolved language-capable hardware. For a long time, that was assumed to be roughly when Homo sapiens took over the world and demonstrated Behavioral Modernity. 70,000 years ago, the most complex art in the world looked like this:

Scratching those hatches doesn’t require theory of mind, language, or symbolic thought. The thinking on display is arguably no more advanced than what animals regularly engage in, and it’s less cognitively impressive than the flutes produced by Neanderthals. By 40,000 years ago, however, humans fashioned Venus figurines and would for another 30,000 years in a continuous tradition:

Animals and Neanderthals don’t make anything approaching this. It’s reasonable to think there was some cognitive evolution between 70,000 and 40,000 years ago, particularly given this is the time frame Homo sapiens began conquering the world. It’s a simple model: as some groups developed language, self-reflection, and symbolic thought, they tended to dominate and expand. In this article, I contextualize why a geneticist who wrote Who We Are and How We Got Here: Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past downplays the importance of genes in explaining the advent of the human condition and the fact that sapiens is the last Homo standing.

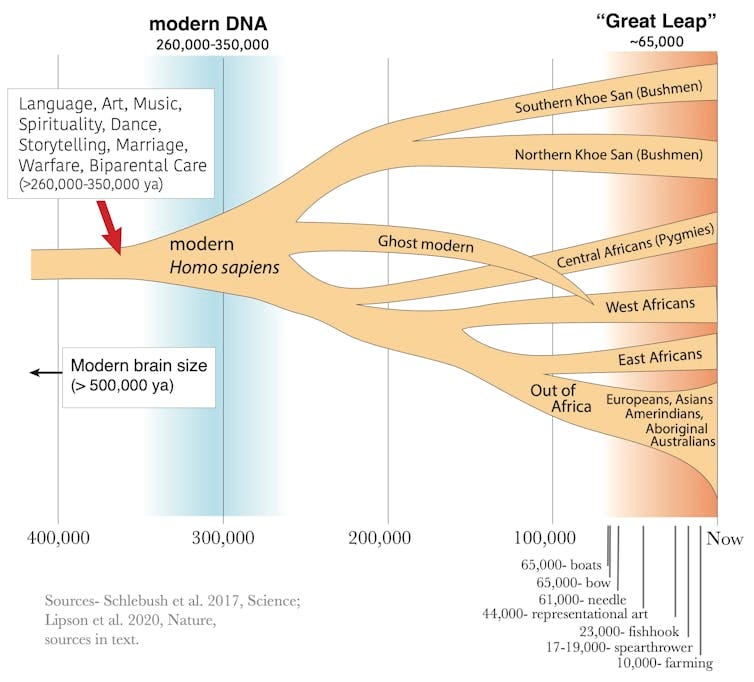

Darwin, still testing our faith

The above diagram depicting when we became fully human was produced by evolutionary biologist Nicholas Longrich. “Modern DNA” is highlighted to have been established 260,000-350,000 years ago, when the Khoi San are estimated to have split from the rest of the human family tree. Language, art, music, spirituality, dance, storytelling, marriage, warfare, and biparental care define our species now, so it is assumed that all of those were fundamental parts of life then as well, even though they are not demonstrated until the Great Leap, starting about 65,000 years ago. In fact, the Sapient Paradox wonders why art, religion, and abstract thought were missing from most of the world until about 10,000 years ago.

Like Reich, Longrich argues humans passed a threshold of cultural complexity that created feedback loops that allowed us to out-compete Neanderthals. Culture evolved, but our brains didn’t. It’s easy to see why this is an attractive model. As Steven Pinker said, “People, including me, would rather believe that significant human biological evolution stopped between 50,000 and 100,000 years ago, before the races diverged, which would ensure that racial and ethnic groups are biologically equivalent.” But is there evidence to support the idea that human evolution effectively hit an “off switch”? And more to the point, what does the data say about recent evolution?

New Findings on Human Adaptation

Just two weeks after the interview, a preprint paper co-authored by Reich was released, titled Pervasive Findings of Directional Selection Realize the Promise of Ancient DNA to Elucidate Human Adaptation. Analyzing the genomes of thousands of ancient DNA specimens, the study reveals strong selection on the human brain over the last 10,000 years.

The grey line shows the estimated change in average polygenic scores (PGS) for intelligence and household income in Europe over the last 9,000 years. A PGS is calculated by summing all the genetic variants that contribute positively or negatively to a trait. While it's an estimate and subject to potential errors, such significant changes are unlikely to be due to chance alone. The magnitude of change is striking: 9,000 years ago, the PGS for IQ was two standard deviations lower than today. If similar changes are projected back 50,000 years, it suggests that most individuals in those populations might not have had the cognitive capacity for fully developed grammatical language or abstract thought.

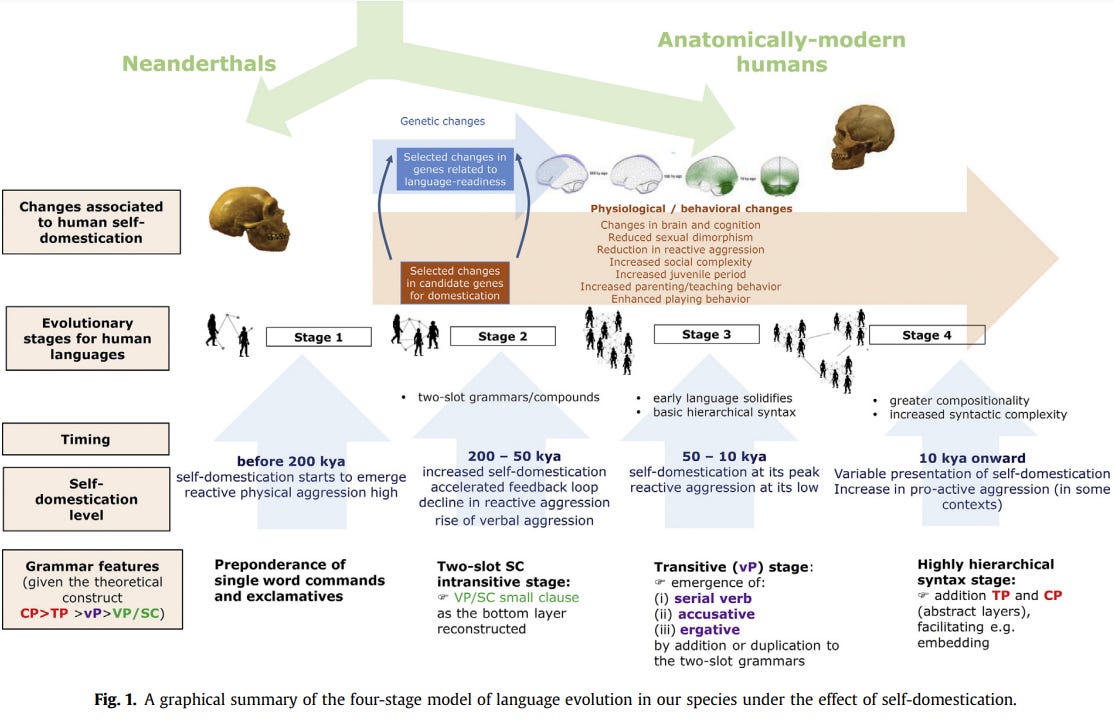

The Evolution of Language

This aligns with certain linguistic theories, such as the one below. There is no need to read it closely; what I want to get across is that serious researchers argue that full language was not established until 10,000 years ago (‘embedding’ in the final stage is also known as ‘recursion’).

This model was published in 2020, and there are others like it. With that in mind, consider Reich’s treatment of the evolution of language:

Reich: There's been one incredibly interesting and weird line of genetic evidence that was so weird that a lot of people I know dropped off the paper. They just didn't want to be associated with it because it was so weird. They just thought it might be wrong. It's stood up, as far as I can tell. It's just so weird…They looked at the set of differentially methylated regions, roughly 1000 of them, that were systematically different on the modern human lineage. They asked what characterized them? Were there particular biological activities that were very unusual on the modern human specific lineage? There was a huge statistical signal that was very, very surprising and unexpected. It was the vocal tract. It was the laryngeal and pharyngeal tract.

…If you think this change in the vocal tract is important in language, which seems reasonable, then maybe that's telling you that there are very important changes that have happened in the last half million or a few hundred thousand years, specifically on our lineage that were absent in Neanderthals and Denisovans.

Patel: To the extent that humans have had it for hundreds of thousands of years, it's not clear then why humans weren't able to expand out of Africa and…

Reich: We don't know that. We just know that today we have it. It could have been only a couple of hundred thousand years ago or 50,000 or 100,000 years ago that these changes happened.

Patel: But then we know all modern humans have them, different groups of modern humans.

Reich: Separate 200,000 years ago.

It’s not surprising that Homo sapiens language abilities are unique, given our singular success. This was the dominant scientific explanation for a long time. In fact, many creation myths say it is language that differentiates man and beast, so similar ideas have permeated folk wisdom for millennia. Further, if the evolution of language followed anything like the four steps above, it’s not mysterious how language could be universal today and non-existent 200,000 years ago. Increasingly complex grammar and culture could spread among populations, leading to selection for enhanced cognitive abilities. This process could occur even between genetically distinct lineages coming into cultural contact after being separated for 100,000 years.

I want to reiterate that such a scenario is not surprising. Consider The Origin and Diversification of Language, a classic from 1971 where Morris Swadesh proposes:

The figure shows waves of more advanced language spreading from Eurasia in the Paleolithic (with Basque-Dennean at the epicenter). Models like this fell out of favor because geneticists showed deep genetic splits in Africa, and it was assumed that there was no significant cognitive evolution in the last 50,000 years (or even 350,000 years). Now, genetics is demonstrating that assumption to be false. Recent evolution is back on the table. Humans aren’t born a blank slate upon which culture writes anything it likes.

You say you want a revolution?

Reich describes how the current standard model of human evolution has been pieced together over time. We sequenced modern humans worldwide, then got ancient DNA from Neanderthals and Denisovans and realized there was admixture. Then we’ve had to do the same for several other irregularities that keep emerging.

“At this point, there's a number of these mixture events that seem increasingly implausible. If you know the history of models of how the earth and the sun relate to each other in ancient Greek times, there's these epicycles that were attached by the Greek, Hellenistic astronomer Ptolemy to make it still possible to describe the movements of the planets and the stars, given a model where the sun revolved around the earth. We've added all of these epicycles to make things fit.”

It’s a remarkable comparison coming from a researcher of his stature. One well-known fact is that everyone outside Sub-Saharan Africa has a few percent of Neanderthal DNA. However, this figure is much lower than it was 40,000 years ago. At one point, Eurasian Homo sapiens may have had 10-20% Neanderthal DNA, which has been selected against since then (it was deleterious for survival).

“If you actually count your ancestors, if you're of non-African descent, how many of them were Neanderthals say, 70,000 years ago, it's not going to be 2%. It's going to be 10-20%, which is a lot.

Maybe the right way to think about this is that you have a population in the Near East, for example, that is just encountering waves and waves of modern humans mixing. There's so many of them that over time it stays Neanderthal. It stays local. But it just becomes, over time, more and more modern human. Eventually it gets taken over from the inside by modern human ancestry.

…It’s not even obvious that non-Africans today are modern humans. Maybe they're Neanderthals who became modernized by waves and waves of admixture.”

If different modern populations are a ship-of-theseus of other Homo species, why was the genus braided together in the last 50,000 years? One conceivable model is that genes and language co-evolved over tens of thousands of years, sending sparks of new ideas, abilities, and people worldwide. At the beginning of this process, each hominin species—Homo neanderthalensis, Denisova, Longi, floresiensis, luzonensis, and archaic sapiens—had its own adaptations and niches. As general intelligence emerged, individuals who could grok symbolic thought survived1. It’s a story of self-creation equal to our species. The sapient hominins—those that threw off the shackles of Eden—are the last ones standing.

In contrast, the prevailing model has language evolving over 200,000 years ago, but it granted no competitive advantage. Then, 150,000 years later, in an essentially random2 process, Homo sapiens outcompeted a half dozen cousin species who had been living for hundreds of thousands of years in their respective niches. Additionally, in the last 200,000 thousand years, evolution stopped influencing the human brain. Instead of speeding up evolution as humans encountered novel problems, and despite our changing skull shape and host of new genes related to cognition, we hit an “off” switch for cognitive evolution, after which the story was entirely cultural—memes evolving rather than genes.

It seems like something’s got to give, particularly because those who argue there isn’t something special about the human mind or that our distinct traits evolved 200,000 years ago also maintain there has not been recent cognitive evolution. As genetics dismantles that view, how will our understanding of our species change?

I bet the spread of genes and culture in the last 20,000 years can fully explain the Sapient Paradox. But time will tell! DNA sequencing is a telescope into the past, and the science is young yet. Like the telescope, it will trample many sacred beliefs. Will those who put faith in the blank slate behave like pre-Enlightenment Catholics? Will academic disciplines schism? It’s going to be a wild ride.

For more on my theory of the selection pressure that made us human, see the Eve Theory of Consciousness. Modern humans are obligate dualists who live their life as a ghost inside a meat machine, but that wasn’t always the case. The sense of “I” is a stable hallucination our species developed in the last 50,000 years. This theory makes predictions, such as Paleolithic humans being much more schizophrenic. Interestingly, that is one of the findings in Reich’s new paper.

This would have included other Homo who were brought into sapiens’ fold.

Reich’s word! See his account of Homo sapiens expansion:

“So a model that might explain the data is that you have sparks coming out of a kind of forest fire of humans expanding in the Middle East or Near East. They come in and they start going to places like western Siberia or parts of South Asia or parts of Europe. They mix with the Neanderthals. They produce these mixed populations, like these initial Upper Paleolithic groups we sample in the record, and they all go extinct including the modern human ones. There's just extinction after extinction of the Neanderthal groups, the Denisovan groups, and the modern human groups. But the last one standing is one of the modern human groups.”

…It's not a triumphal march of superiority and inferiority with the group that now comes in having advantages and somehow establishing itself permanently. What you have is a very complicated situation of many people coming together and natural disasters or encounters with animals or encounters with other human groups. It all results in an almost random process of who spreads or ends up on top and other groups coming in afterward.

...It's very tempting to think that at some level—I'm not trying to be politically correct—that it's something innate, some better biological hardware that makes it possible for these African lineages to spread into Eurasia. I have no good insight into that topic. I don't think there's very good genetic evidence or any other kind of evidence to say that that contributed in a very strong way. It’s just complicated.”

So I asked a similar question to a statistical geneticist (Gusev) whose priors are a bit different than Reich's (as he thinks recent selection is very uncommon and not on social/cognitive traits). He had a three-part principle-based response for explaining the likely trajectory of modern human cognitive repertoire: 1) Locus specific selection/hard sweeps are extremely rare (this is still largely consistent with the new Reich paper). 2) There isn't any current evidence that individual variants were involved in the great leap forward (The new Reich paper is consistent with this too as we're talking about directional selection on standing polygenic variation for the the complex traits). 3) Background selection (slow, persistent purging of novel alleles) explains the majority of human genetic variation.

The takeaway is that modern human cognitive abilities are likely much much older than when we can find evidence of them in the archaeological record. We can't generate great genetic insights because there isn't any DNA left from this period and we don't have great samples of ancient African DNA where a lot of important things happened. None of this forecloses mean or variance differences between different populations (Reich covers this in Ch.11 of his book). So the recent paper is observing interesting changes at the margin rather than the core of human capacities. Plus, whatever the human base cognitive capacities are, I think it's clear the special sauce is networking more and more individual human brains and preventing knowledge/technological decay over time. I think this also contributes to the Sapient Paradox as the learning curve to conscious sophistication with modern human hardware was itself gradual too. Recent changes are very interesting and meaningful (they do disrupt some dogma), but I don't think they remake how we understand the brain evolution that contributed to our core cognitive capacities.

There is more in the Reich book about why it's likely we emerged slowly. Even looking at how neurodevelopment and cognition are disrupted genetically today is revealing. The contribution of de novo variation is very important because the really important stuff is at fixation and constrained. Only really dramatic, typically new or less penetrant mutations/genetic changes (large deletions, trisomy 21, recessive LOF, etc) are culprits behind catastrophic intellectual/developmental deficits. We're still learning a lot on this front too like the recent snRNA gene findings (https://www.nature.com/articles/s41591-024-03085-5).

On top of that, current GWAS don't support a 50% heritability for personality and intelligence, although I hope there are some things these methods are still missing. But I wouldn't bet my money on it. For example: CNVs, mtDNA (intelligence is more strongly correlated with the mother), Y chromosomes (bottlenecks), epigenetics (I don't think so), epistasis, etc.