Venom & Valhalla

The Mistress of Serpents Goes North

A commenter pointed out two episodes in Norse mythology where women use snake venom to give powers to men.

Hǫðr slays Baldr

Long ago, when gods and men still contended for love and glory, the mortal Hǫðr challenged Baldr, the shining champion of the Æsir, for the heart of Nanna. The god won the first battle, as they often do, but Hǫðr escaped with his life. Stumbling into the woods, bruised and bleeding, he chances upon three maidens preparing Baldr’s secret dish.

“Now they had three snakes, of whose venom they were wont to mix a strengthening compound for the food of Baldr, and even now a flood of slaver was dripping on the food from the open mouths of the serpents. And some of the maidens would, for kindness sake, have given Hǫðr a share of the dish, had not eldest of the three forbidden them, declaring that Baldr would be cheated if they increased the bodily powers of his enemy.”

Saxo Grammaticus, Gesta Danorum (c. 1185-1220; The Deeds of the Danes), Book III, trans. Oliver Elton

In the end, Hǫðr slays Baldr, but it is a pyrrhic victory. Pyre-ric, even. The gods lay Baldr on his ship Hringhorni and kindle a vast funeral pyre. As Nanna watches her would-be lover burn her heart bursts and she dies1.

Snake-Spit Porridge & the Accidental Sage

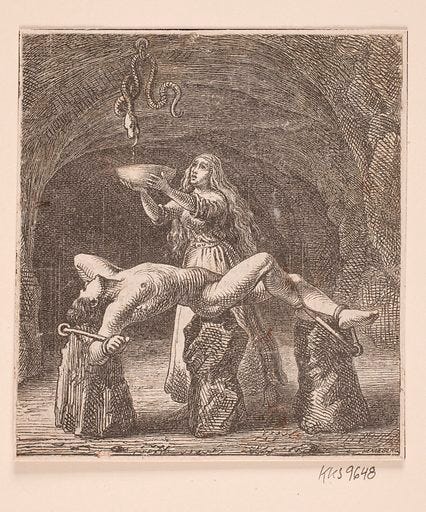

In a later generation of heroes, half-brothers Erik and Roller get clandestine help from their mother, Kraka:

“Roller was sent by his father to find out what had passed at home… he perceived his mother stirring a cooked mess in an ugly-looking pot, three snakes hanging above, their slaver dripping on the meal… When the dish came forth, Erik, judging by its inward strengthening, slyly turned it and claimed the darker share. From that single savoury mouthful he ‘attained the highest pitch of human wisdom,’ able to read the voices of cattle and wild beasts and to adorn every word with witty adages.” ~Gesta Danorum, Book V

The draught opens Erik’s ears and sharpens his tongue: he parses beast-speech, reads others motives “as one reads runes,” and talks in well-turned proverbs. Later adventures show him using bird-speech to scout enemy positions, soothing assemblies with silvered counsel, and guiding Roller out of political snares.

Mistress of Animals

I intended to leave the post as a simple observation, logging these as possible echoes of the Snake Cult of Consciousness. But the myths intersect with EToC in ways that go beyond the obvious repetition of women using venom for male fortification. Scholars link this very tri-snake motif to the Mistress of Animals, a well-documented archetype running through the heart of the Snake Cult2.

The Mistress of Animals—Potnia Theron to the Greeks—stands astride myth and prehistory: woman grasping or flanked by creatures, typically serpents, cats, or birds; ruler of the untamed. She marks humanity’s ability to bend the wild to its will. Her expressions are many. What follows is a brief tour beginning with examples firmly accepted by scholarship before venturing into more speculative terrain.

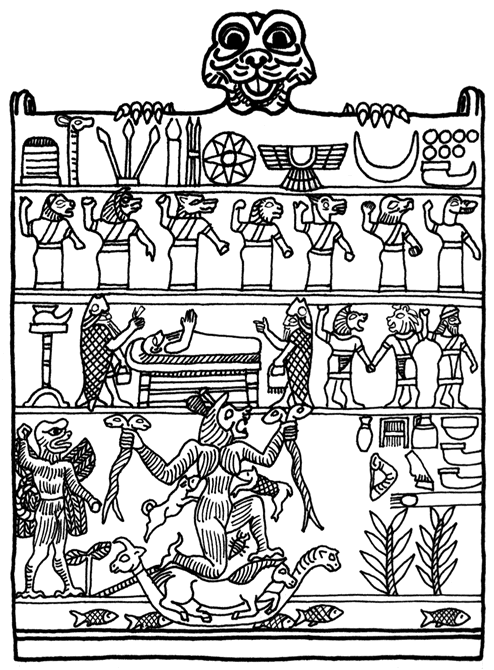

The snake-witch stone pictured above is a classic Norse rendering of the Mistress, and one reason scholars connect her with our two snake myths. Relevant to this blog, The Mistress of Animals is also connected to Eve in the goddess Qetesh in Egypt:

Though Egyptian, her name is actually Semitic in origin, literally meaning “The Holy One” or “She Who is Sacred.” Footnote 33 of EToC v3 features her Near Eastern counterpart Asherah3, who some scholars argue is the Canaanite snake goddess that became Eve. Remember, if venom was ever actually used ritually it’s interesting that both goddesses hold a lotus, which, like apples, is a good source of rutin, an effective antivenom4.

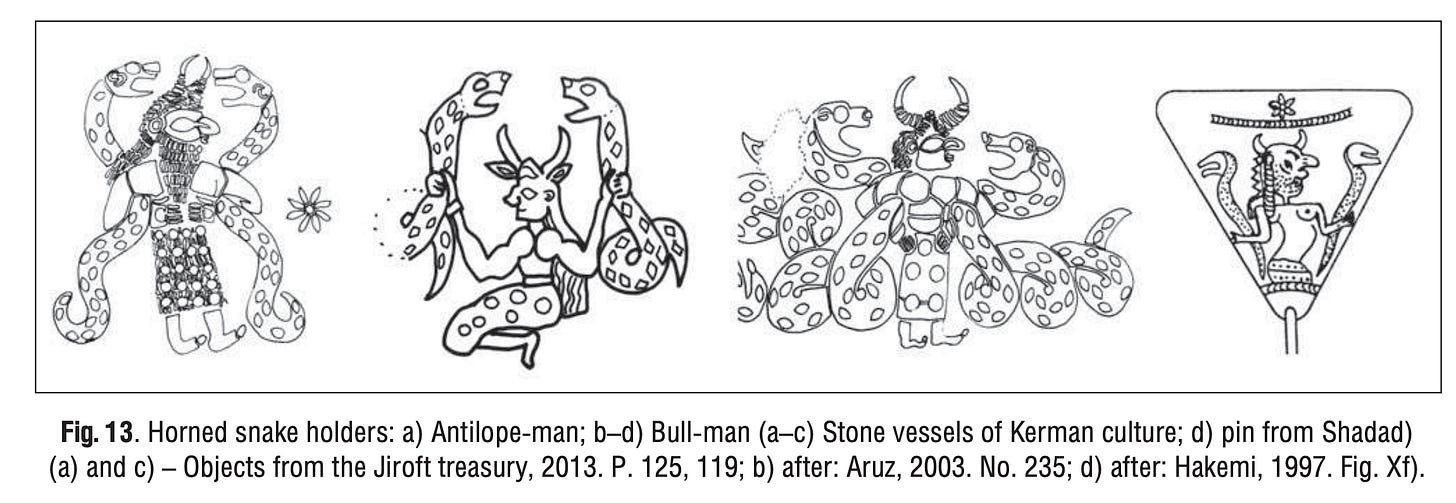

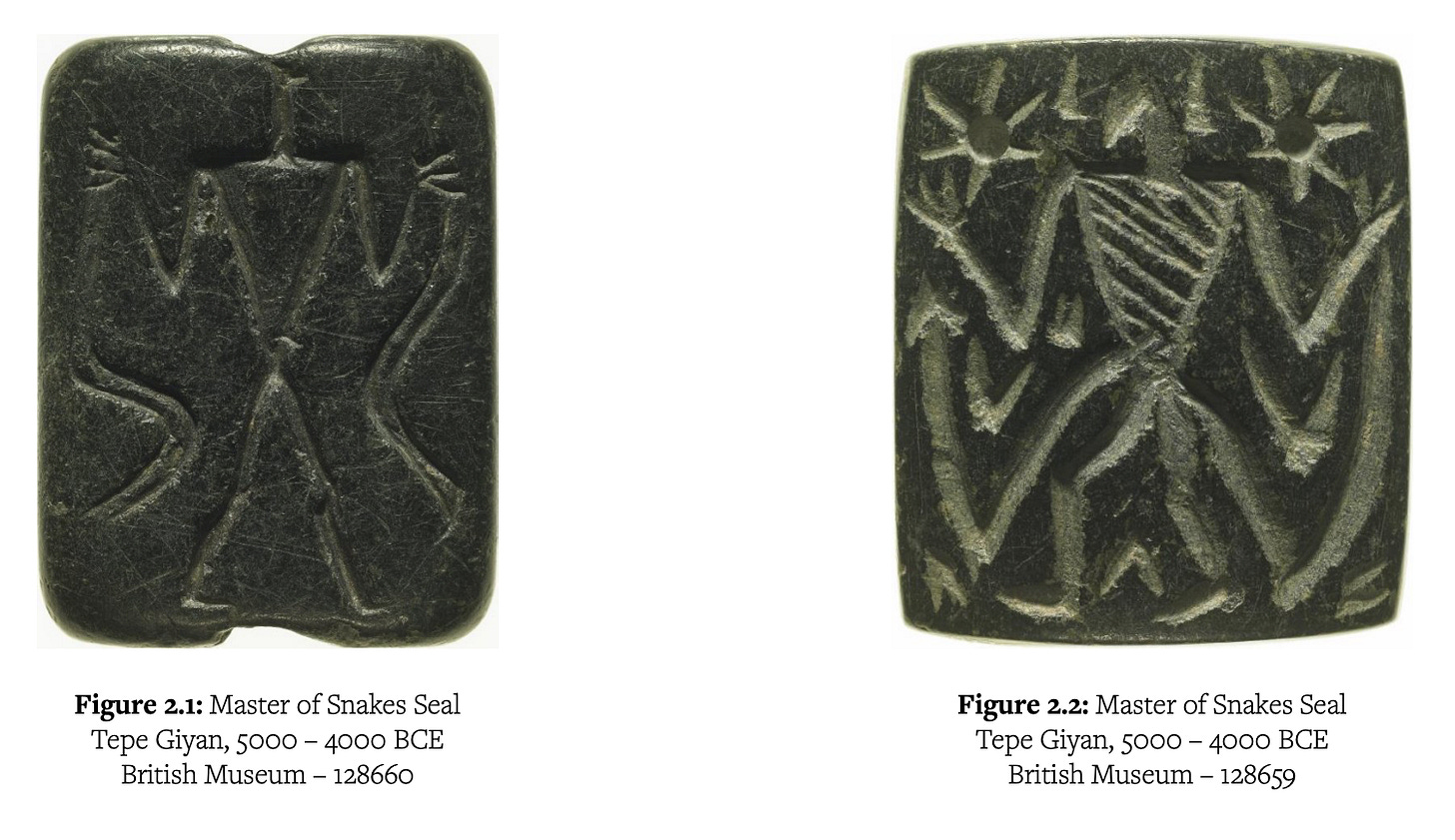

In Iran, the Mistress (or Master, unclear here) of Animals goes back even further, to 5000 BCE:

It’s quite a common figure in the region5, spanning thousands of years, and sometimes identified with the Persian dragon Aži Dahāka, who demands the brains of young men as tribute:

Over in Crete the schema blooms as the famous snake goddesses:

One reason I am interested in tying the Norse myths of snake venom to the Mistress, is there are many reasons to believe her Mediterranean incarnations actually dealt in venom. Going back to the first century BC, Diodorus reported that the great mysteries—including Eleusis—spread from Knossos6. In those rites initiates felt “the deity gliding over the breast” (a living serpent), and Dionysian temples kept a live snake78. Outside those cults, it is well documented that health potions in antiquity contained venom9.

Taking things back in time, art historian Merlin Stone argued these Greek cults were remnants of a Paleolithic tradition that used snake venom as an entheogen: “the chemical makeup of certain types of snake venom may have caused a person… to feel in touch with the very forces of existence,” and “the sacred serpents… were perhaps not merely the symbols but actually the instruments” of revelation. I go further, arguing the snake-mistress cult discovered ways to teach self-reflection, and much of world culture stands on its foundation.

Independent researcher Richard Cassaro treats this archetype much like my white whale the bullroarer: evidence of a shared cultural root across the globe. He even calls it the “Godself Icon”, echoing my contention that the Snake Cult could make one “as the gods.”

This graphic casts a wide net. If the examples in the Old and New World share a common root, then one has to posit significant mid-Holocene diffusion (not widely accepted), or the icon going back to the Paleolithic, even though the earliest known examples are those Iranian samples 7,000 years ago. But resolving those issues is well beyond the scope of this post.

Whether or not one buys the worldwide coverage, Paleolithic continuity, or ritual drug use, the Norse episodes are at least a late northern branch of a very ancient tree. The persistent pairing of women, snake venom, and special knowledge in that branch is unmistakable. And hard to explain by coincidence or evolutionary psychology.

Loki Bound

There is another ancient strain in the Baldr saga. In one version the gods hold Loki responsible for the death. In vengeance they chain him beneath a dripping serpent until the world ends, protected only by the good will of his doting wife Sigyn, who catches what spittle she can. Going back to at least 192410, this has been understood as a cousin to the myth of Prometheus and other bound tricksters, such as the Persian antihero Zahhāk from whose shoulders grow serpents that demand the brains of two young men every night11. (Recall he was depicted as a Master of Serpents, like the antecedents of Eve and Demeter.)

The Bound Trickster:

These are all Proto-Indo-European (PIE), suggesting a time depth of ~6,000 years for the original tale. Going back even further, archeologist Jacques Cauvin argued that both the Prometheus and the Fall of Adam and Eve are memories of the transition to the Holocene ~12,000 years ago. There is a poetry to this view. In Genesis, Lucifer, like Prometheus, brings forbidden knowledge and light, and is punished for defying the divine order. The New Testament even has him bound for 1,000 years. If Cauvin and I are right, the two bound tricksters are the same character, kept alive since the foundation of human civilization. Both strands of Western thought, Athens and Jerusalem, remembering how we became human12.

Finally, another IE trope present in the Norse tales is serpents granting beast-speech. The porridge gave Roller the ability to talk to birds. In another Norse tale the dragon-slayer Siegfried hears bird-speech after tasting Fáfnir’s blood. Or consider the Greek Melampus, whose ears are opened by snakes. I wrote about an Anatolian case in Secrets of the Snake King, which explains the origin of medicine. For a wider survey see GPT’s Deep Research Snakes That Bestow Beast-Speech in World Mythology.

Conclusion

The old Norse tales have women using venom to amplify men, a practice they associated with the Mistress of Animals. This Mistress is widespread, rubbing shoulders with Eve, Greek Mystery cults, and a Persian dragon demanding boys’ brains. Other threads in those myths connect to Prometheus, the God Self, snake speech, and the origins of medicine.

There are many open mysteries about how human culture came to be, and why it appeared so late. What was that transition like to live through? There is ample evidence that myths can last that long, and my bet is they have answers. Proceeding on this premise, I keep finding snake priestesses.

The pyre scene is from Snorri’s version of the slaying of Baldr, and not included in Saxo’s.

Hermodsson, Fornvännen 95 (2000): analysis of Smiss III and its tri-serpent composition.

Gotlands Museum note explicitly tying the stone’s three snakes to Guta saga’s dream of three serpents; cf. Peel’s translation.

Pearl, “The Water Dragon and the Snake Witch,” Current Swedish Archaeology 22 (2014), ties Smiss to other serpent/dragon myths

Even with the Semitic name and almost identical iconography, ChatGPT assures me that scholars have moved on from believing Qetesh was a Near Eastern import of the pan-Canaanite goddess Asherah. This is partly a semantic dispute and it relented when I pushed back, but reflexively deploying the “well actually” logic of a splitter is extremely annoying, and at least partially due to Chat being trained on academic writing. It’s a low-effort way to defend one’s turf as a specialist in the Systems Theory of Late Ramesside Amuletic Glyptic, which no expert in Levantine Votive Stelae and Theonymy (Iron I) could ever hope to fully grasp. Only a rube would think the Egyptians borrowed a Goddess.

The Egyptian god Bes is also associated with both snakes and Lotus, holding them in the same position. In Drinking with the Gods: The Chemistry of Bes Rituals I discuss a psychedelic potion discovered in a ritual Bes jug. Below is a Ptolemaic period (300-30 BC) stele featuring Horus beneath Bes, holding snakes, scorpions, a lion, and an oryx in classic “Master of Animals” pose:

Diodorus Siculus, Library of History 5.77.3–4 (1st c. BCE), trans. C. H. Oldfather, Loeb Classical Library, vol. III (1939). Quote: “…the initiatory rites observed in connection with the mysteries were handed down from Crete…” and “…at Cnosus in Crete it has been the custom… that these initiatory rites should be handed down to all openly…” Speaker:Diodorus reporting the Cretan claim (applied to Eleusis, Samothrace, and Thrace).

Clement of Alexandria, Protrepticus (Exhortation), 2.17. Quote: “The token of the Sabazian mysteries to the initiated is ‘the deity gliding over the breast,’—the deity being this serpent crawling over the breasts of the initiated.”

Art Institute of Chicago, Tetradrachm Depicting a Cista with Snake (curatorial text notes the snakes used in Dionysian initiation were kept in the cista).

Galen, On Theriac to Piso (attests viper as an ingredient in theriac)

D. Karaberopoulos, “The theriac in antiquity,” The Lancet 380 (2012), includes viper flesh as a standard component.

Dumézil, Georges. Le Festin d’immortalité : Esquisse d’une étude de mythologie comparée indo-européenne. Annales du Musée Guimet, Bibliothèque d’études 34. Paris : Paul Geuthner, 1924. (see esp. pp. 92-94 for the Loki/Prométhée parallel)

Yes, the brain was understood as the seat of the intellect.

Like me, Cauvin also saw the Greek Mystery cults as a descendent of the Fertile Crescent’s Neolithic initiatory kit.

Has anyone experimented with these types of venoms on apes?

Can you draw up a timeline of when humans gained consciousness and these traits diffused, or have you already done so?

I've read a lot of your posts and they sound compelling, but I get this feeling that you're trying to build a storyline out of evidence that spans tens of thousands of years.